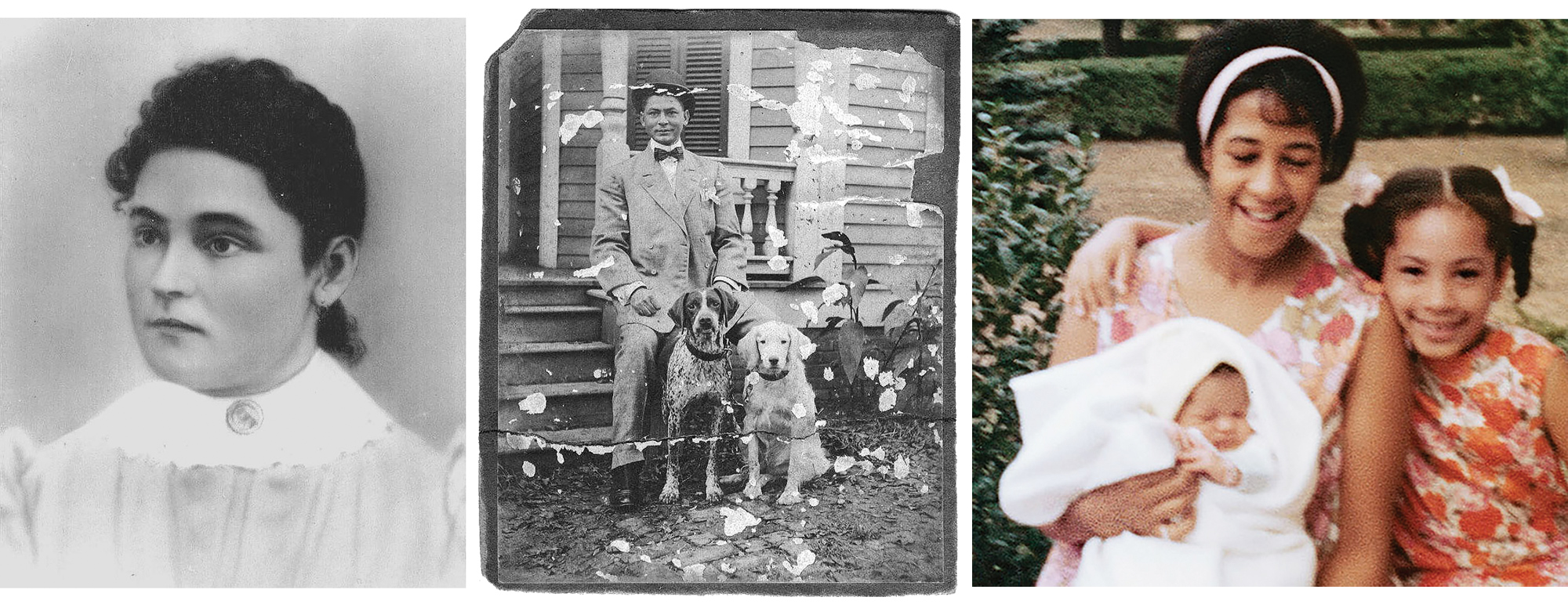

In Lorene Cary’s latest memoir, her grandmother’s illness motivates her to reflect on her family’s history, shaped through migration, marriage, death, birth, and illness, as well as the national legacies of slavery and Jim Crow laws. Cary, C’78, G’78, and a lecturer in English, published Ladysitting in 2019.

The memoir begins when Cary’s grandmother, Lorene Cary Jackson, can no longer live on her own. Cary opens her home and becomes a caregiver. In this excerpt, she remembers childhood weekends at her grandparents’ house in New Jersey, a place she considered a respite from her own home in West Philadelphia. This passage reveals Cary’s lifelong interest in gathering family stories and the challenging nature of memory.

· · ·

On our leisurely weekends, I asked Nana questions to try to elicit her stories in long form. What she gave, what my father later gave, her nubs, thumbnails, beats. Example: “My only memory of my mother was her sending me into the field to pick cotton to stuff a doll she was making for me.”

The family came north the year Nana turned six. Soft cotton bursts the boll in the fall, but sharp spurs on the tips stick the fingers of even experienced pickers. Other hazards: cockle burrs in the rows stick to clothing; saw briars cut the legs and feet; various insects, including the notorious pack saddle, bite and sting. Would Nana’s mother, Lizzie E. Burnet, wife of a landowner, even if she were busy with other children, have sent six- or five- or four-year old Nana into a field to harvest even a few tiny handfuls of cotton alone? Did Lizzie grow ornamental cotton near the house just for this purpose, as our own neighbors did in Pennsylvania. (“Every child oughta know cotton!” said Aunt Bea from Georgia, wife of Uncle Fletcher, who believed that pure tobacco never hurt anybody, but that “devilish filters” were causing lung cancer.)

But, back to Lizzie: suppose she grew just enough cotton to make dolls, like we grow herbs in pots by our back doors in the city. Would she have sent a young child out to get her fingers pricked, and, as one of my granddaughters says, “cry-cry-cry”?

Once I had my own daughters, and once I had studied cotton enough to write books about the South, these were my new questions. But throughout my childhood, Nana repeated the same story, almost word for word.

· · ·

Lorene Cary, C’78, G’78, has been a lecturer in the Department of English since 1995. She is the founder of Safe Kids Stories, an online collection of stories and multimedia, and Art Sanctuary, a community organization that uses Black arts to enrich the Philadelphia region. Her first book, Black Ice, is a memoir of her experience as a Black student at a prestigious New England boarding school. Her novels, The Price of a Child and If Sons, Then Heirs, tell stories of the historical and contemporary effects of slavery in the U.S. Cary wrote the script for The President’s House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation, a multimedia exhibit at Independence National Historical Park.