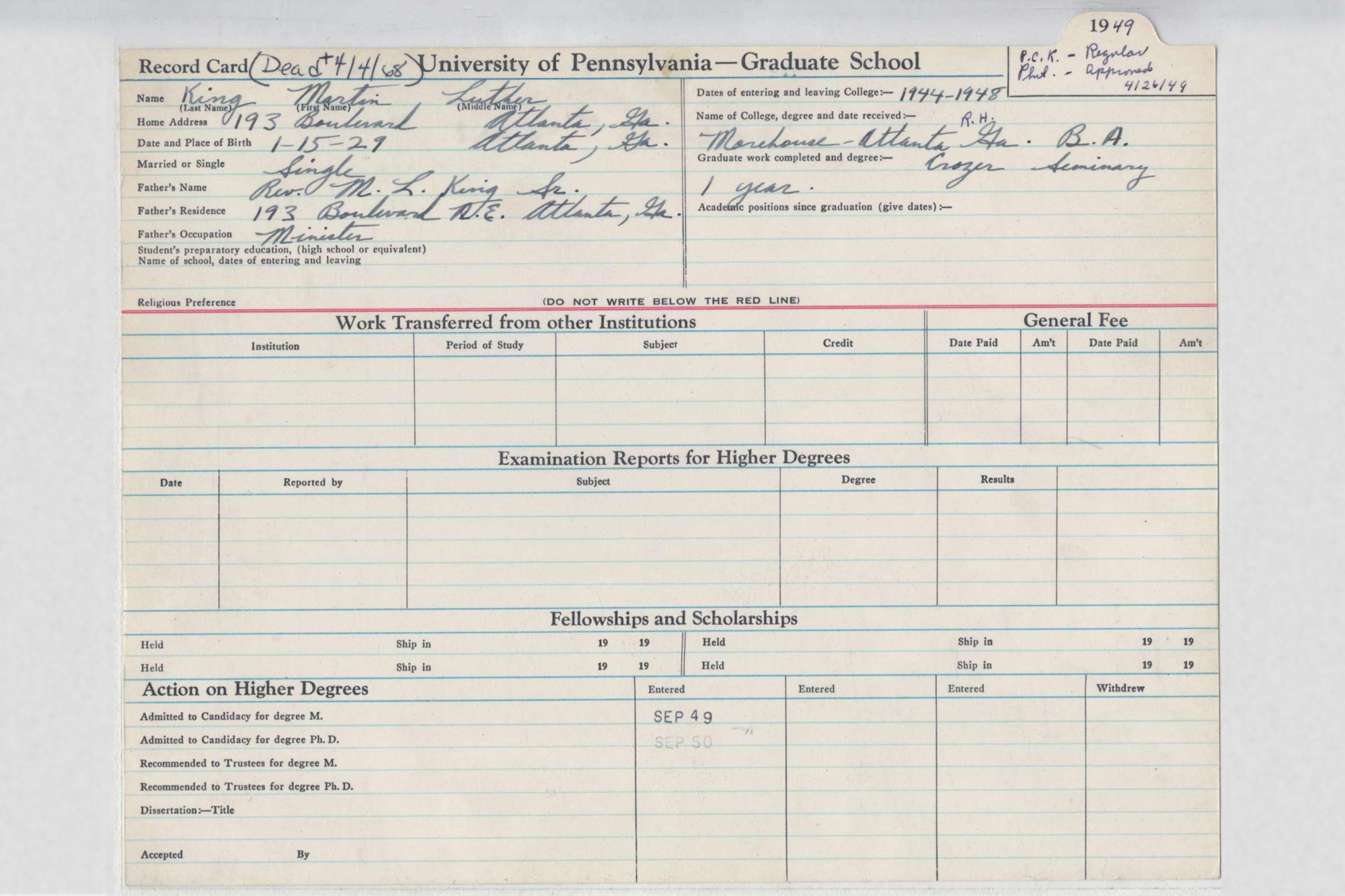

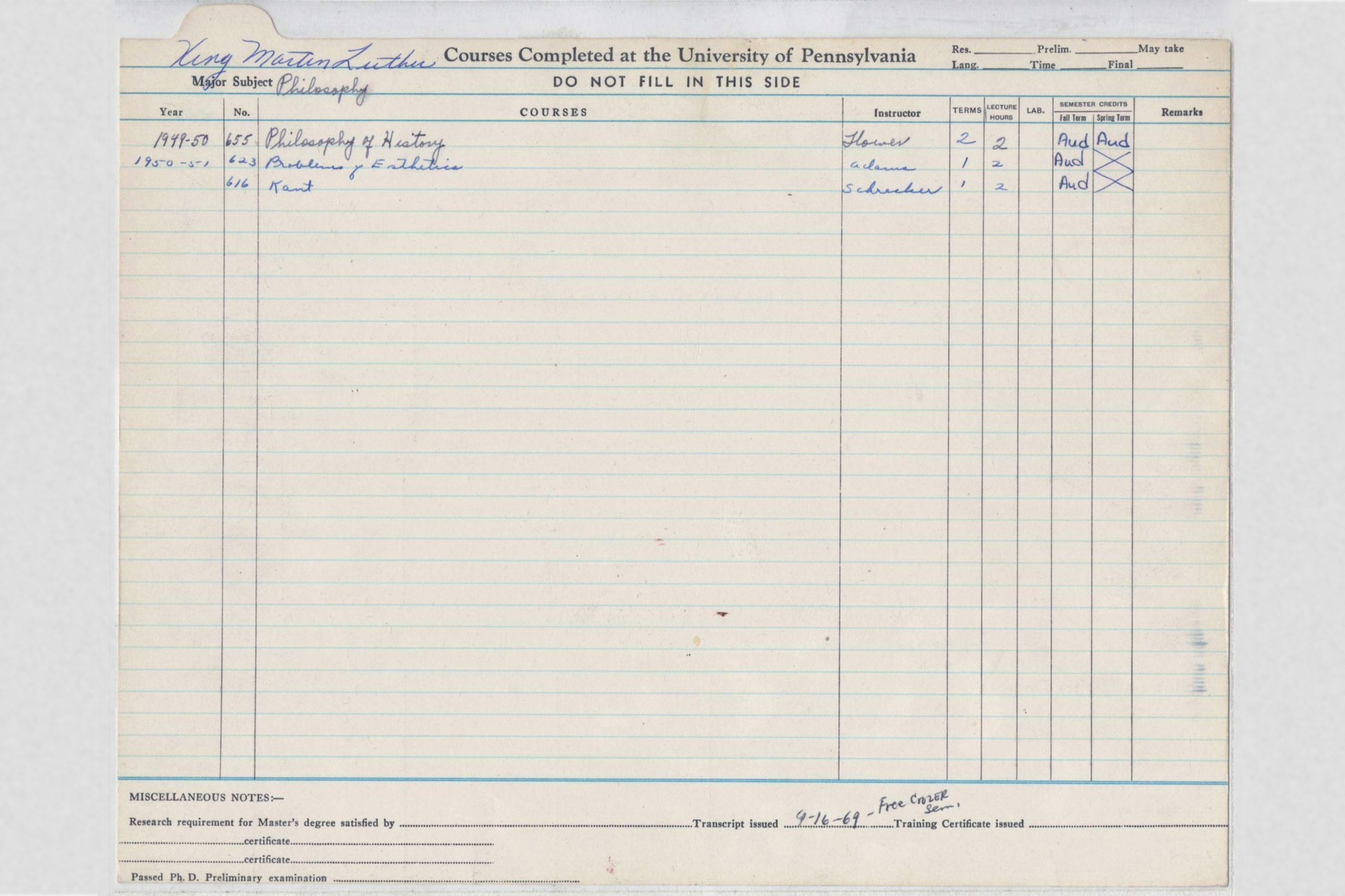

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Martin Luther King Jr. audited three courses in Penn’s Department of Philosophy—Philosophy of History, Problems of Esthetics, and Kant—two of which are still taught today in some form. The original record card listing the classes lives in the University Archives, a visual reminder of the time the 20-year-old future Civil Rights leader spent on campus. King fit the Penn classes in between those he was taking at nearby Crozer Theological Seminary.

“There’s always been a strong link between theology and philosophy, at least historically,” says Gary Hatfield, Adam Seybert Professor in Moral and Intellectual Philosophy. “Theology was seen as having a kind of philosophical foundation, though that’s of course a simplification.”

Hatfield himself is an expert in Immanuel Kant, a field that has evolved since King studied it with Professor Paul Schrecker. “When I went to school in the 1960s and ’70s, it was common to separate Kant’s various interests,” Hatfield explains. “Now it’s not acceptable to just look at one side of Kant, to be a specialist in metaphysics and epistemology or a specialist in ethics and politics. Now it’s crucial to always have in mind a wider context, to include other writings of Kant and historical conditions in Germany when he was writing, in the latter part of the 18th century.”

Similarly, the field of aesthetics, sometimes called the philosophy of art, has also changed in the decades since King took Professor Elizabeth Flower’s class; the scholarly area now incorporates a wider range of reflections on art and beauty in nature, focusing on works of art in greater depth, according to Hatfield. He adds that Flower—whom he knew personally—“would’ve likely been heavily into the social and political dimensions of aesthetics. I have a sense that she would’ve included a strong dose of that in her class.”

Even without seeing the notes King took in these courses or the syllabi the professors created for them, the record itself offers a snapshot, a moment more than a decade before King’s “I Have a Dream” speech when he was simply a student honing the knowledge and skills that would later shine through in his oration.