The Monstrous and Mythical

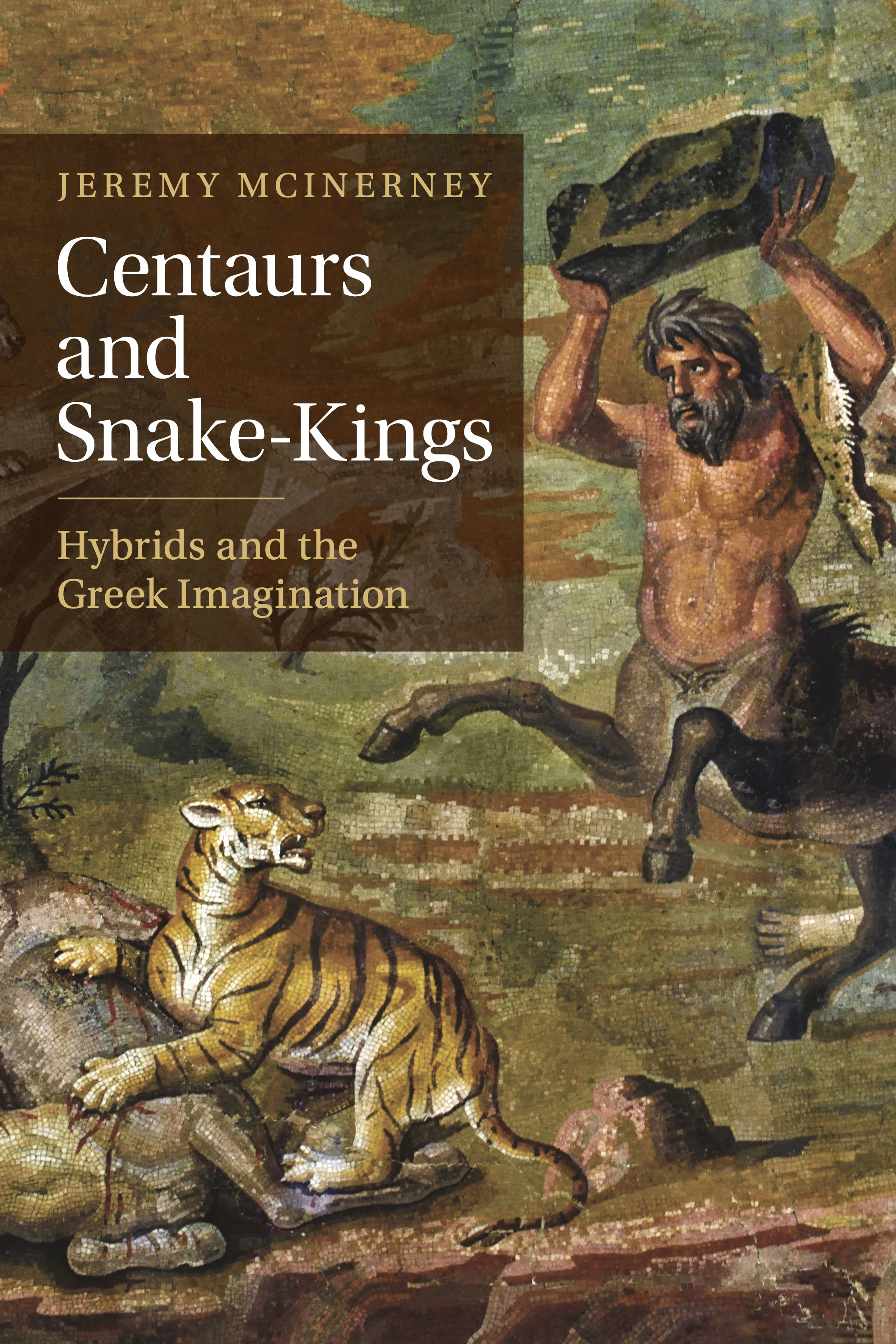

In his book “Centaurs and Snake-Kings: Hybrids and the Greek Imagination,” Jeremy McInerney, Professor of Classical Studies, investigates the power of hybridity in myth.

As a Greek historian covering the archaic classical and Hellenistic periods, Jeremy McInerney has moved, over the course of his career, from a traditional political military style of ancient history into areas of cultural history. This scholarly path led to his 2010 book, The Cattle of the Sun: Cows and Culture in the World of the Ancient Greeks, which examined the cow’s role in everything from Greek communal life to religious sacrifice to dietary regimen.

“The book was a blast to write, but when I was invited to a conference in the aftermath of it being published, I said to the organizers, ‘I’d love to give a paper, but I don’t want it to be about cattle,’” says McInerney. “I didn’t want to be sucked into doing the same thing over and over.”

As fate would have it, around that time, McInerney was visiting the Archaeological Museum of Argos, and as he walked in the door, in the very first display, he was greeted by a striking statue of a centaur.

“It was a human being, all the way from head to foot,” says McInerney. “The horse’s section was literally stuck onto the back, where you’d have a human backside. I hadn’t seen centaurs like that before, and I became fascinated by the question of what happens when a centaur goes from being human all the way down to stopping at the waist and then becoming a horse.”

Thus began McInerney’s investigation into Ancient Greece’s love affair with hybridity, which resulted in the recent Centaurs and Snake-Kings: Hybrids and the Greek Imagination. The book is an examination of hybridity and the themes and messages such creatures evoked, such as the instability of identity and warnings about trespassing against cultural mores and conventional values.

“The Greeks are already thinking about what we would call super ego, ego, and id, but they’re using different methods to explore it,” says McInerney. Centaurs, for instance, were associated with lust and excess in Greek myth. The fact they are half—or more than half human (the museum statue included human genitalia)—adds yet another layer of symbolic complexity.

“If you look at the pediments of the Temple of Zeus and Olympia, for instance, they depict centaurs carrying women off, so the Greeks have this very powerful way of dealing with what they regarded as the deepest, darkest human urges,” says McInerney. “We see these types of examinations famously on the stage: Oedipus kills his father and sleeps with his mother and all those terrible things. What I wanted to do with this research was continue to explore how they are using hybrids in a similar fashion.”

Depictions of hybrids—composites of humans, animals, and/or the monstrous, ranging from Medusa to the griffin to the Pegasus—date back to Minoan culture at the end of the Bronze Age, between 1500 and 1200 BC, McInerney explains. This includes figures borrowed from Egyptian culture and the ancient Near East. “Greek historians have tried to tease out whether some of these hybrids, when repurposed by the Greeks, took on the same meaning or something totally different, and the answer seems to be no—the repurposed versions could have some totally different symbolism.”

McInerney cites Hello Kitty as a contemporary example.

“For our culture in the West, it is largely just kittens with big eyes and merchandise sold to pre-teens,” he says. “But in Japanese culture, kawaii, the notion of cuteness, is a really well-anchored idea that goes back hundreds of years.”

You can kind of go from monster to human to monster. The way I think the Greeks think of this is almost the way we regard DNA as being intertwined.

McInerney says that hybrids became a bedrock of Greek culture around late-8th century BC, when the poet Hesiod, in his work “Theogony,” ruminated on the origins of the Greek gods.

“There was this idea in ancient Greece, which is pretty foreign to most modern people, of generations of Gods,” he says. “And the movement between those generations often tells you how the Greeks and people of the ancient Near East also saw themselves in relation to the past. During this particular period, the movement consisted of the shift from titanic monsters to Gods that look like you, in other words, a world of anthropomorphic gods.”

Hesiod, McInerney continues, depicted characters who give birth to a generation of hybrid monstrosities, including three sisters called Gorgons, the most famous of which was Medusa, whose mythical gaze had the ability to petrify any who locked eyes with her (requiring Perseus to use a mirrored shield to defeat her). When Medusa is killed, “her head comes off, the blood spurts forth, and it gives birth to two creatures,” says McInerney.

One is Pegasus, the winged horse. The other is a man named Chrysaor who has children with a human woman. Some of those children are monsters. “So, you can kind of go from monster to human to monster,” McInerney says. “The way I think the Greeks think of this is almost the way we regard DNA as being intertwined.”

Man and Centaur. Bronze, ca. 750 BC. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.190.2072 (Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In addition to art and literature, hybridity was also often showcased in physical form. McInerney’s personal favorite is Bluebeard, a figure portrayed with three human torsos and three heads, each with a beard; the torsos then morph into snake coils. Bluebeard appears in the corner of a temple pediment, and McInerney’s theory is that representations such as this are what the Greeks called the Tritopatores, or the “great grandfathers and their ancestral spirits.”

“The Athenians had a lot invested in the idea that they were born of the earth,” says McInerney. “When the Persians were invading, the Athenians all thought that Athena had abandoned the Acropolis because the snakes that lived there were gone.” The disappearance of the snakes was a negative notion for them, he adds, but feelings about snakes in Greece remain complicated to this day. Some people keep them as pets, but McInerney says that once, while he was living in Greece, he witnessed a bus driver jam on the brakes and reverse up the road to kill a snake.

And though hybridity was often used as a sort of warning against taboos or a compass for cultural mores, not all cultures considered hybrids monstrous, McInerney says. He mentions the character Hermaphroditus, the original hermaphrodite. Though it was seen as a monster in Ovid’s poetry because the gods fused a nymph and a youth, creating something in between, the people of Halikarnassos (modern Bodrum in southwestern Turkey) considered Hermaphroditus the perfect embodiment of a male-female union.

“There are versions of Aphrodite from that region that are bearded,” says McInerney. “There are stories that some of the priestesses of Athena, in times of great danger, would actually grow a beard. There are many, many ways in which gender, and particularly cis-gendered bodies, are constantly facing a kind of resistance and a recognition that there are other possibilities.”

In modern times, hybridity continues to evoke strong reactions. “In psychological studies in the ’40s and ’50s, where American college students were shown different versions of hybrid bodies, people had the most problems with the ones that were human bodies with an animal head,” says McInerney. “In fact, they often dismissed the hybrids as people wearing masks.”

And while hybrids of the hideous ilk, like Medusa, and modern hybrids like the Wolfman, continue to fascinate and terrify the modern audience, beauteous examples also grace the pages and reels of kids’ stories. “Pegasus is probably the best example,” says McInerney. “There is no version of Pegasus that is monstrous. It can go faster than us, it can carry us, and then on top of all of that, you give it wings—it’s a doubling down on positives.”

Now, McInerney is turning to two other projects: a retelling of the Persian Wars that tries to strip away the Greek bias of most accounts, and a study of “living” and “dying” in Ancient Greece. “This tackles the lives of ordinary Greeks and will incorporate recent work on understudied areas such as food and diet, magic and sorcery, and the importance of women, foreigners, and the enslaved to the survival of Greek culture.”