Prospecting Playbills

Michael Gamer, Professor of English, and Scott Enderle, Digital Humanities Specialist at Penn Libraries, are designing a database to classify historical playbills.

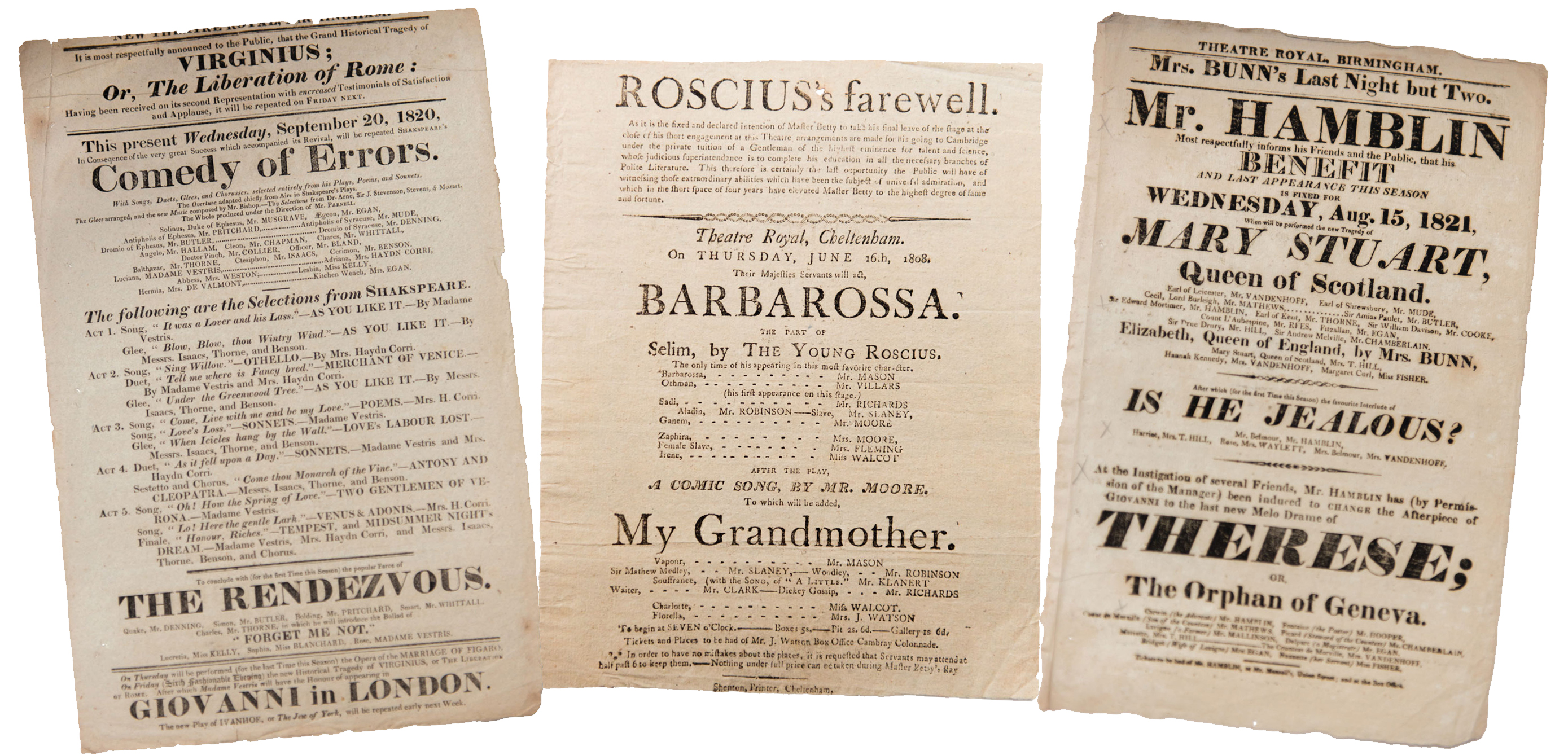

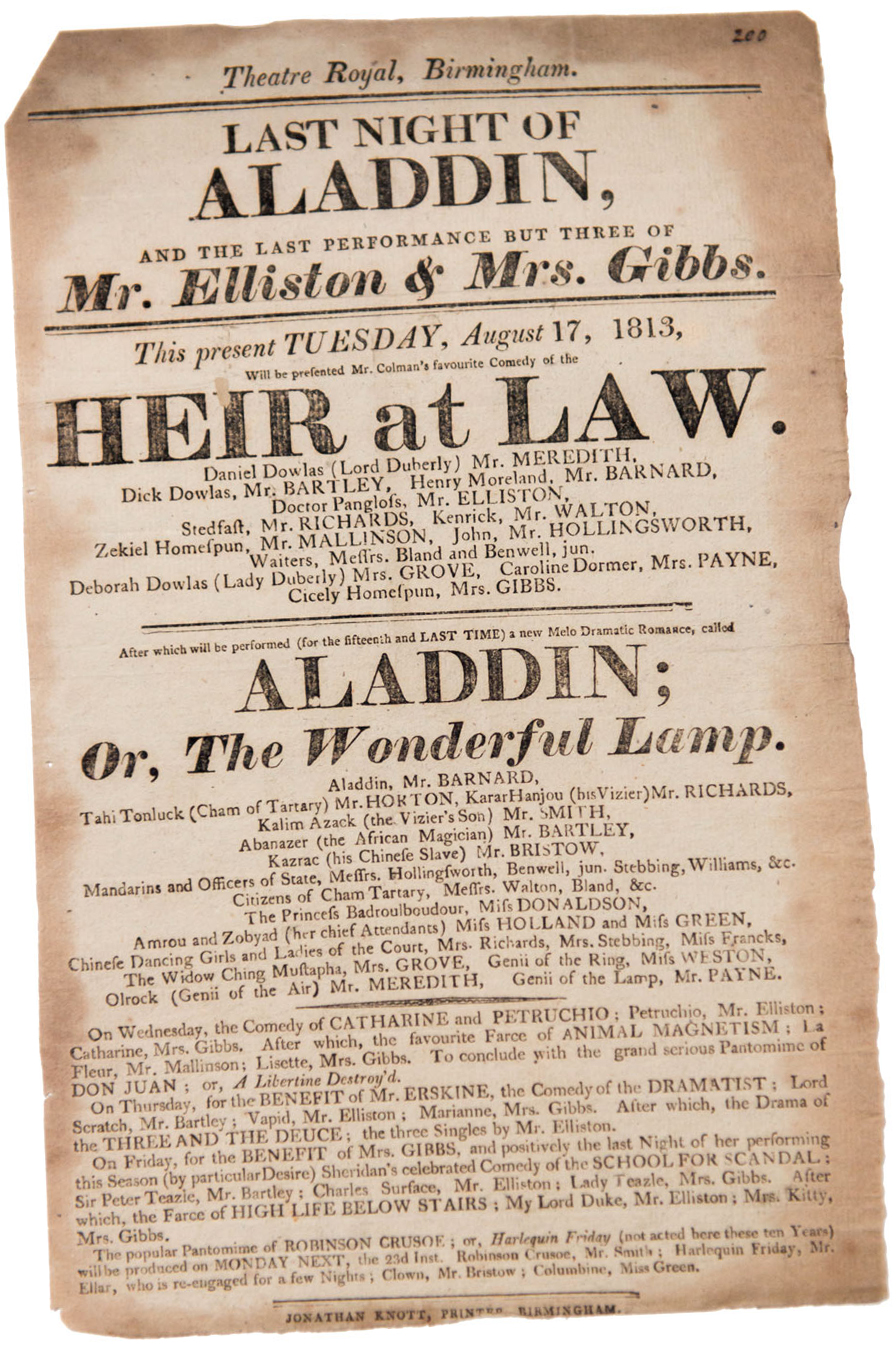

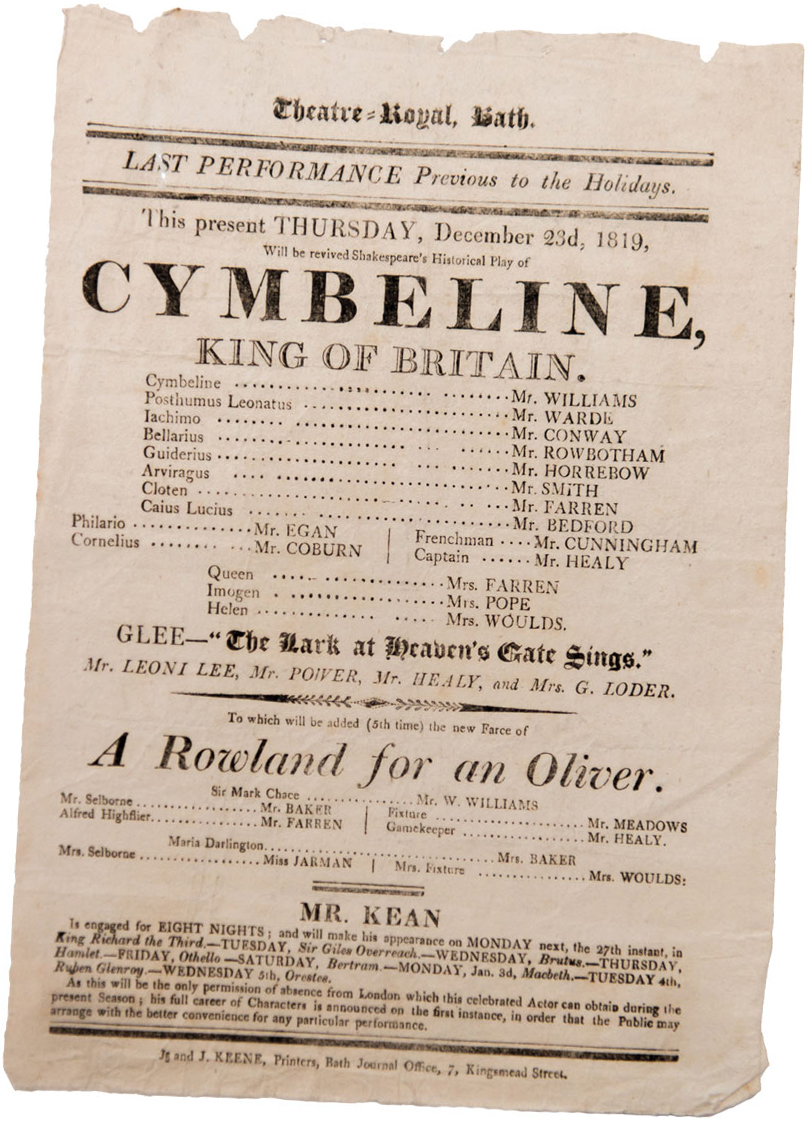

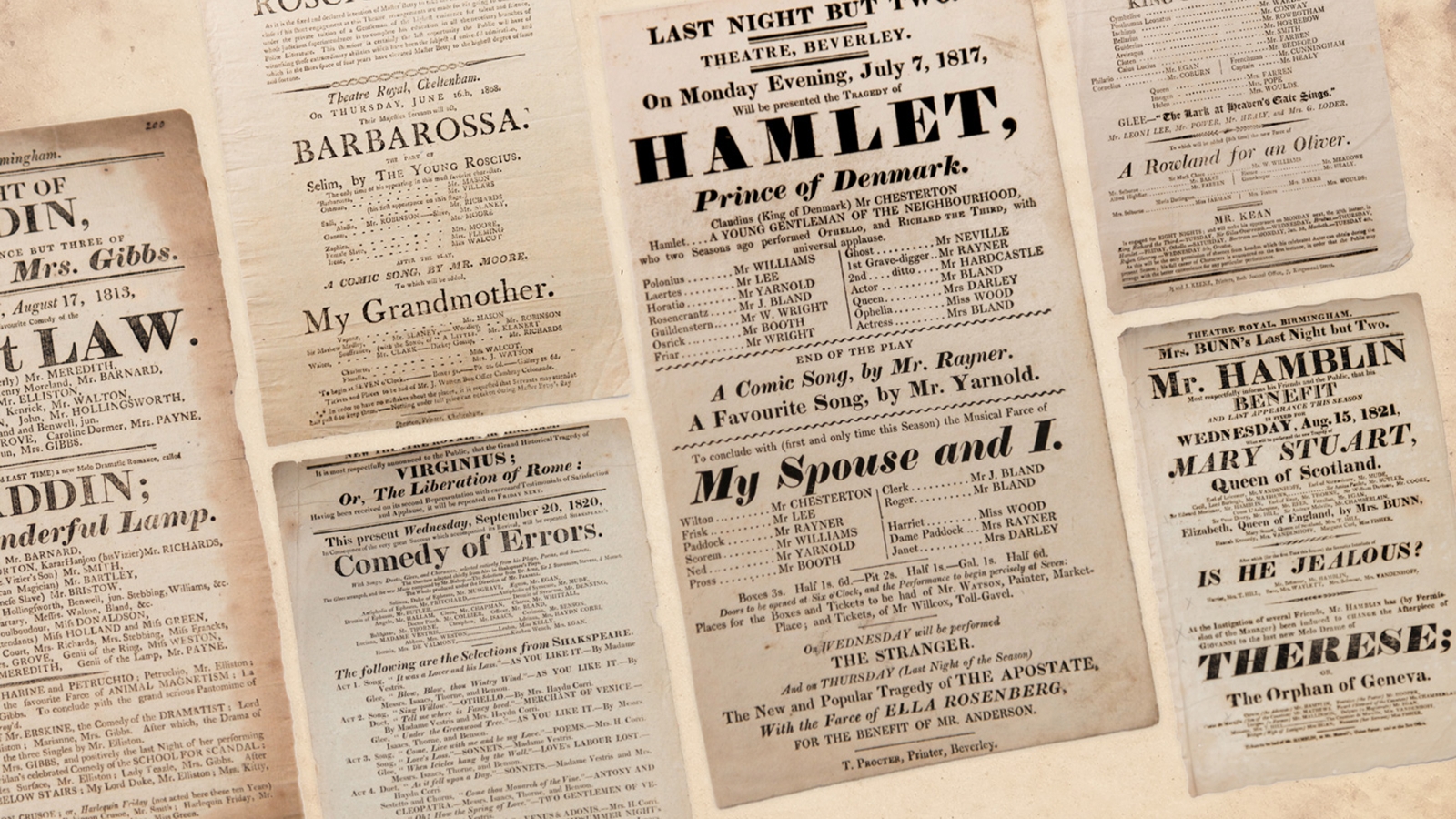

Playbills for 18th- and 19th-century dramatic performances such as this one are not only engaging, but filled with valuable information for researchers. How to capture and catalogue all of those varied, and often quirky, details for meaningful analysis? Neither a method nor a database exists.

Until now.

Michael Gamer, Professor of English, is collaborating with Scott Enderle, Digital Humanities Specialist at Penn Libraries, to design a database and online data-entry form to tag and classify the myriad descriptive elements in playbills.

The database will be searchable, allowing researchers such as Gamer to ask and answer questions that were previously impossible to pursue with certainty. “What else can playbills tell us other than what they are designed to tell us?” Gamer asks.

“Where did new dramas go after they premiered in London? If you have enough playbills, you can map that, and even imagine the lifespan of a play” adds Gamer, who is writing a book about English melodrama, Staged Conflicts. “Similarly, where do actors and actresses come from before they get to London? Which theaters are feeders for them? You could figure out those relationships, and how they change over time.”

Boxes and Boxes of Playbills

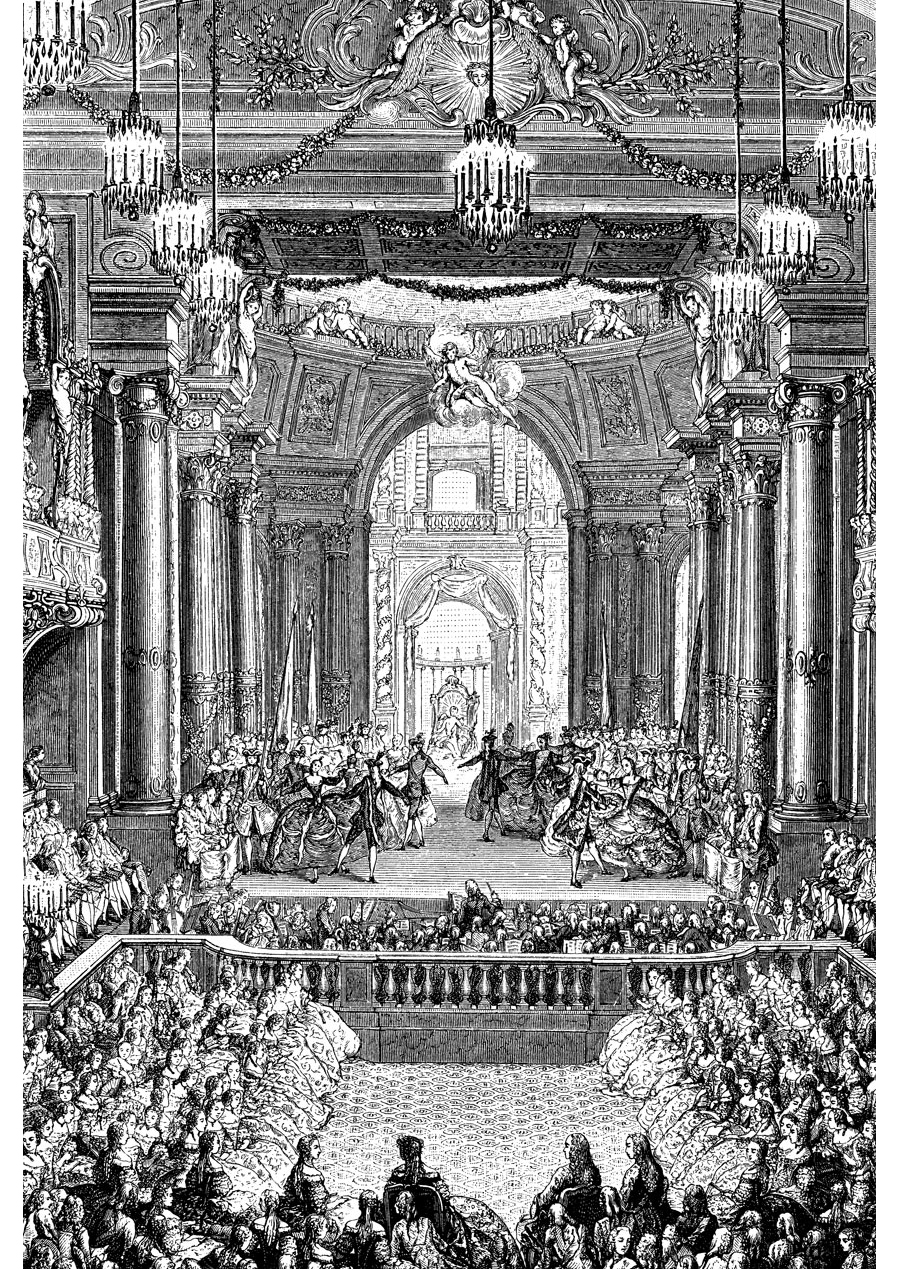

The raw materials of theater history in the 1700s and 1800s are primarily playbills, along with newspaper theater reviews and advertisements. “People obsessively scrapbooked the way that people today have Pinterest accounts,” Gamer says.

That’s why libraries have boxes filled with playbill collections, and some are beginning to be made available online. The British Library recently digitized its entire collection of 18th- and 19th-century playbills and made them publically available—60 gigabytes of playbill data from 1770 to 1850 alone.

The Penn Libraries have a “treasure trove” of playbills from England and America, says John Pollack, Research Curator at Penn Libraries.

The Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts holds more than 6,000 playbills from before the 20th century, half in archival boxes and half in bound volumes. Among them are playbills from the entire run of Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Theater. The Center additionally holds more than 8,000 playbills from the 20th century to now. About 600 of Penn’s playbills have been digitized.

But digital copies are not searchable data, so Gamer and Enderle are setting out to capture the data from an estimated 250,000 English 18th- and 19th-century playbills from the British and Penn library collections. Penn student interns started inputting data last summer, as the team helped to fine-tune the database's structure and its online data-input form. The long-term goal is to turn to crowdsourcing.

“No theater historian has been able to work with this quantity of data. You physically can’t,” Gamer says. “If I wanted to know how many performances the actor John Philip Kemble did in York in his career, or even get a sense of it, there is little way of finding that out without this type of database.”

The initial phase of the project has been funded by an incubation grant through the School’s Price Lab for Digital Humanities.

“We love that the project is using computers to ask research questions that would have been tough—if not impossible—to answer otherwise; to see patterns that are hidden in the mountain of data they are pulling together,” says Stewart Varner, Managing Director of the Price Lab. “It is also giving students the opportunity to get real experience working on a digitally enabled and collaborative project. This means they will learn tech skills as well as organizational skills.”

Last summer two interns, funded by a grant through the Penn Undergraduate Research Mentoring program, helped develop the database forms while starting to input the data. Gamer expects to engage additional Penn interns this summer.

“This project was a great introduction to how we study English in an academic way, and especially how the digital humanities are beginning to be used,” says Samantha Claypoole, C’20.

Intern Imani Davis, C’20, an English and Africana Studies major, says the project also provided her a chance to conduct research on her own project about “how Blackness was performed on the British stage.”

Provincial Productions

The provincial playbills—those not from London—are what Gamer and Enderle find the most interesting.

“Those who write about the history of the stage often focus on London,” says Gamer. “We figured we’d get the biggest bang for our buck by starting with provincial playbills, because so little is known about the provincial theaters. During these centuries the stage was fairly rigidly censored, especially London theaters, but also any of main theaters in provincial cities, so productions involving politics were often added to existing plays.”

The last line of the 1790 playbill for The Belle’s Strategem and Harlequin Foundling is an important clue in understanding of the power of provincial plays, he says. The production was highly political, performed in an industrial town in the north a year after the start of the French Revolution.

“These are the people of Hull at a very partisan time, not dissimilar to our own, proclaiming liberty in defiance of the policies of a Church-and-King authoritarian government,” Gamer says. “They are saying: we love the French democratic revolution and we want to celebrate it with a dance of fairies in the Temple of Liberty.”

Using the new Penn playbill database, a researcher will be able to isolate, for example, the special performances to commemorate, celebrate, or condemn Bastille Day after the French Revolution. The ability to search in such detail will be important for Gamer’s book, as he plans to include a chapter surveying how British theaters responded to the battle of Waterloo, focusing on the years 1815 to 1820.

Model Night at the Theater

Creating the fields on the form to capture that data was the challenge for Enderle, who earned his Ph.D. in English at Penn in 2011.

“We created a data model that can incorporate diverse information of interest to scholars from many different fields. That meant finding a way to represent the data in the playbills that is not standard,” Enderle says.

Traditional library data models are set up for titles and authors, which doesn’t apply well to playbills. Other playbill databases currently under development are focused on simple transcription, where data is either uncategorized or only in the simplest ways, marking title, date, playwright, director, actor, and role.

The Penn data model has more than 50 possible fields in categories that can be expanded to include even more.

“We intentionally did not adopt a fixed scheme because these playbills have so many different kinds of contributors other than authors. We didn’t want to throw that information out in case it was interesting to a future researcher,” Enderle says. The database has a “contributor” field that can include the name, as well as the position, like playwright or dance master or fireworks manager.

“This way, if you're interested in plays that have a certain musical conductor or scene-painter, you can find them. You will even be able to search by ticket price,” Gamer says. “You could search for every play in the database that had a six-pence ticket. If you wanted to know the cheapest plays in Britain in 1800, you could find out.”

During the summer, student interns Davis and Claypoole flagged the challenges they faced categorizing the data as they went along. As a result of their feedback, Enderle and Gamer tweaked the model. “In those first weeks of summer, Imani and Samantha really helped design the database,” Gamer says.

The team realized the minor and unusual details were often the most challenging to handle, but essential to include for future researchers.

“Something seemingly inconsequential on a playbill, like the name of its printer, could be as important as the leading actor,” Davis says. “I think that's remarkable, and can teach a lot about the value of process.”

For example, one challenge is how to categorize a special feature performance “In the character of a SAILOR by Mrs. Southgate?” or “A Clown’s Flight?” or a “Bevy of Nymphs”? Or, in an 1820 playbill in Penn’s collection, a performance of Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors featuring a dozen songs from other plays, amounting to an unlikely production of Shakespeare's play as a musical?

“One of the real challenges was figuring out a way how to classify things that aren't common—and which often are the most interesting,” Gamer says. “We went through every single data-entry field painstakingly, discussing it with the team, revising as we went along.”

A critical decision was to input data exactly as presented. “We decided early on that we were only going to be interested in what the playbills actually said,” Gamer says. “Working with metadata librarians, we realized that if we were trying to figure out the truth behind the playbills—such as the author of an obscure play for which no print copy exists—we would frequently be wrong.”

The Penn team is collaborating with a project at Texas A&M University developing software that can read and transcribe 18th- and 19th-century fonts, using Optical Character Recognition.

“You could search for every play in the database that had a six-pence ticket. If you wanted to know the cheapest plays in Britain in 1800, you could find out.” - Michael Gamer

Transcriptions can be important for researchers because they make data searchable in simple ways. However, the use of transcriptions for research is limited, he says, especially with large quantities of data. A search for "York," for example, could bring up thousands of results: York the place, York the theater, York as a name, York as a character.

The team at Penn is working to combat the limits of transcriptions. “With our structured data model you could ask for all the plays in 1793 acted at the York Theater with an actor named York,” Gamer says.

Future Roles

About 1,000 playbills were put into the data model by the Penn student interns last summer. The team decided to focus on the years 1814 to 1819, the period after the French Revolution.

“We are just getting started,” Enderle says. The database may be made public in 2019 and then the project may go to crowdsourcing to input the data, following a set of prompts. New crowdsourcing tools are available to check and correct.

“It looks daunting, but it only takes about 10 to 15 minutes per playbill,” Gamer says.

Davis says the experience of working with the playbills has been important to her academic research and future career.

“I was challenged to work well both within my field and outside of my comfort zone,” Davis says. “As a scholar of Black literature, I learned the proceedings of handling research on a large archive of work without getting overwhelmed.”