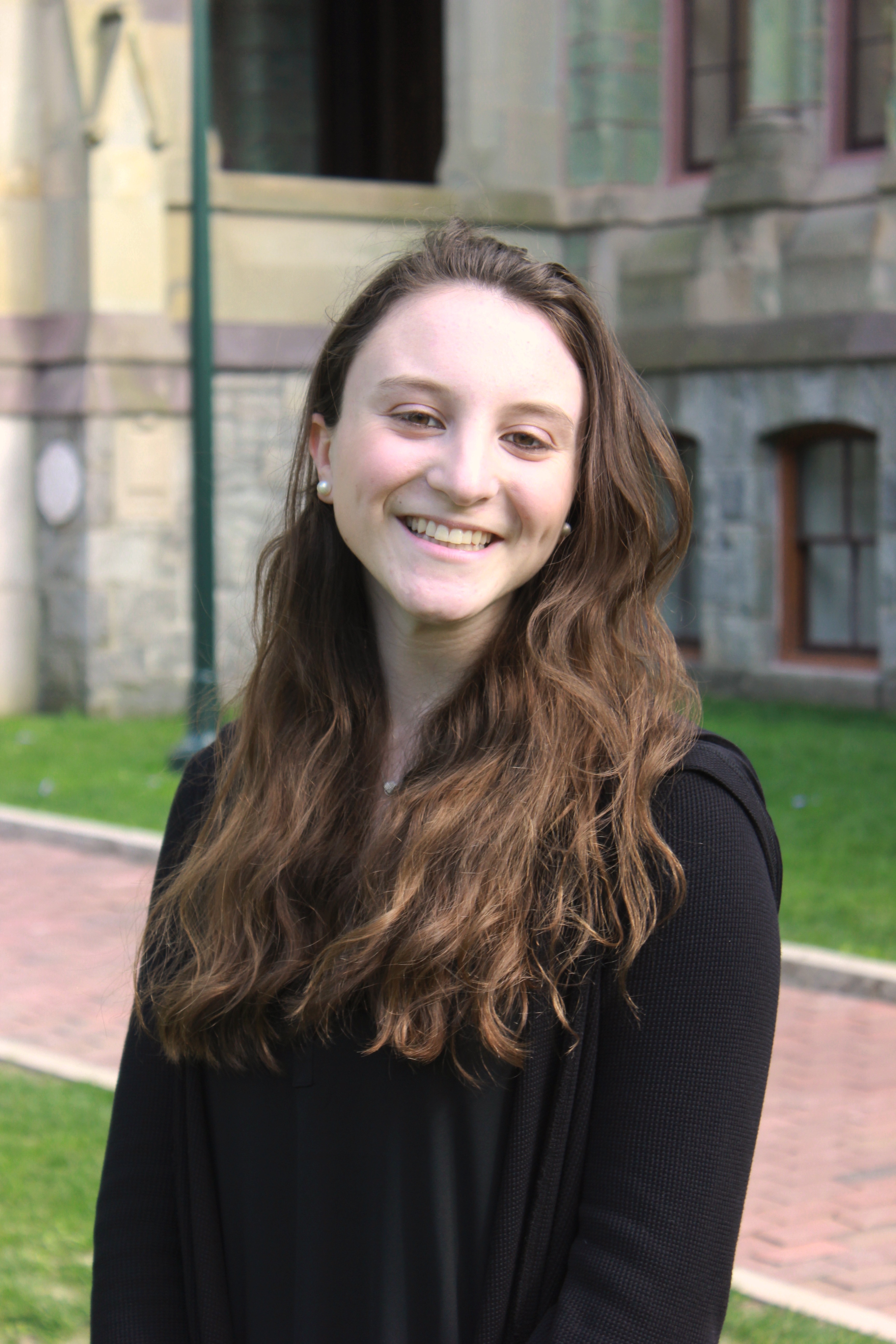

Alisa Feldman, C’18, spent 13 years in Jewish day school before attending Penn, but never dreamed she would spend the summer before her senior year studying in vitro fertilization (IVF) practices in Israel. Her honor’s thesis project, “Be Fruitful and Medicalize: IVF Risk Communication and the Politics of Assisted Reproduction in Israel,” investigates how providers communicate—or don’t communicate—the risks of IVF to patients and the factors that shape those communications. The project won four prestigious awards and earned her a coveted Fulbright Scholarship to continue her research after graduation.

A health and societies major with a minor in gender, sexuality, and women’s studies, Feldman was intrigued by the pronatalist, or birth-promoting, policies of Israel. It is the only nation in the world that pays for unlimited in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments for all women between ages 18 and 45 until they have two children.

Sociological and anthropological literature suggests that Israeli providers tend to downplay the risks of IVF to their patients. Feldman wanted to understand why, yet, she says, there was no existing research on the topic.

Backed by five undergraduate research fellowships and grants, Feldman traveled to Israel. Fluent in Hebrew and armed with a background in Jewish studies and history, she interviewed 21 IVF providers to find out how they communicate with patients.

Feldman found that IVF providers often used pronatalist language or undertones to encourage patients to undergo IVF treatments. She explains, “Physicians are not immune to the influences of pronatalism, and that became clear through my research. The Israeli cultural, political, religious, and social pressure to reproduce plays a role in shaping providers’ perceptions and communication.”

Feldman will conduct another sociological study on IVF and infertility in Israel next year—interviewing couples who have adopted or experienced infertility struggles—through her Fulbright Scholarship.

“My undergraduate research experience was eye-opening for me,” says Feldman. “I never realized how much my religious studies and linguistic background would benefit me in college and beyond. It’s been exciting to see it all come to fruition this way.”