A Proud American

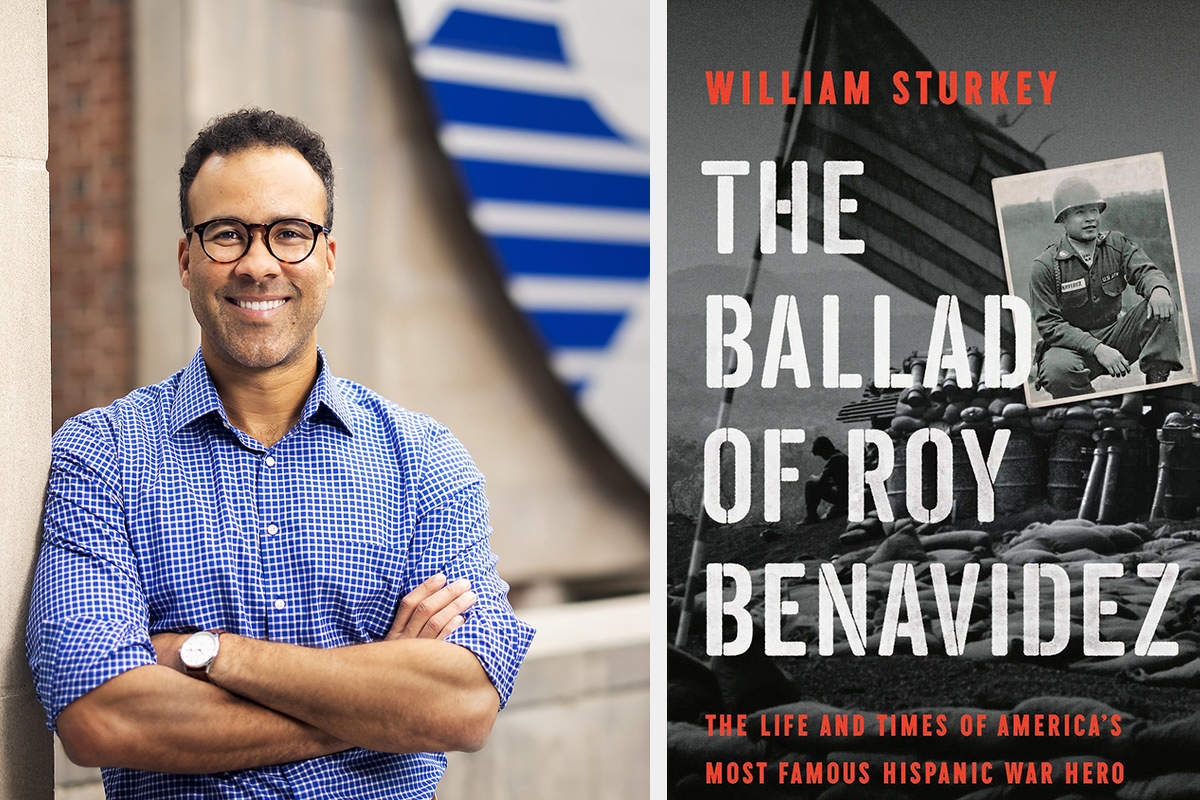

In his new book The Ballad of Roy Benavidez, historian William Sturkey explores the life of this Hispanic war hero, his fight to maintain veteran disability benefits, and the ways in which Hispanic Americans have long shaped U.S. history with scant acknowledgement.

Roy Benavidez was a celebrated war veteran who earned the Medal of Honor for rescuing eight of his comrades during the Vietnam War and later became a popular motivational speaker. He was also a Mexican American who grew up in Jim Crow-era Texas, saw the military as a pathway out of poverty, and who, after becoming severely injured during his time serving, had to fight to retain his disability benefits when the Reagan administration threatened to cut them.

The full and often incongruous life of Benavidez—a self-proclaimed patriot whose very Americanness and right to American freedoms were questioned by many around him—is the subject of the new book, The Ballad of Roy Benavidez: The Life and Times of America’s Most Famous Hispanic War Hero, by William Sturkey, an associate professor in the Department of History.

Sturkey first learned about Benavidez’s story in 2006, when popular YouTube videos of his speeches began circulating. The talks inspired Sturkey, at the time a graduate student, to research the veteran’s military heroics, leading him to headlines from 1983 about threats to Benavidez’s disability benefits. Though Benavidez successfully lobbied Capitol Hill—helped by a media blitz—to reconsider the cuts to his and thousands of other veterans’ benefits, the injustice left an indelible mark on Sturkey, who grew up just outside of Erie, Pennsylvania, in a community that sent dozens of young men and women into the Middle East during the War on Terror.

“I have so many friends who joined the military to go to college,” says Sturkey, who graduated high school in 2000, just 15 months before 9/11. “They didn’t know they were going to go to war, and I hope our nation cares for them as much as it says it does.

“Roy was shot seven times, had 37 puncture wounds from bayonets and shrapnel, and received the Medal of Honor. He was feted at the Pentagon by President Reagan himself, and only two years later, was told that none of that was enough to entitle him to disability benefits,” Sturkey continues. “This great gulf between how we celebrate veterans versus how we actually treat them really resonated with me.”

So did the fact that although Benavidez would grow up to become an American war hero, as a child, he couldn’t enjoy the same freedoms as many other Americans around him; the Jim Crow laws prevented Benavidez from sitting in his local movie theater or going to the restaurants in his neighborhood. Thirty years later, Roy was ordered to fight for freedoms that he “didn’t even enjoy in his own country as a child. His life is one of such stark inequality,” Sturkey says. “As a historian who’s always been interested in marginalized individuals, I was grabbed by Roy’s story in a profound way and knew I had to tell it.”

Benavidez passed away in 1998 at the age of 63, so digging deep into his life meant extensive research and conversations with his surviving relatives, primarily his three children. “I wanted to give Roy the intellectual treatment that rich, powerful white men get,” says Sturkey, whose book is the first to offer a full account of Benavidez’s life. “And I wanted to tell not just the story of his life, but also show how his life is a mirror that reflects the underrepresented histories of Hispanic Americans in this country.”

I wanted to give Roy the intellectual treatment that rich, powerful white men get. And I wanted to tell not just the story of his life, but also show how his life is a mirror that reflects the underrepresented histories of Hispanic Americans in this country.

The 464-page book, published in June by Basic Books, delves into Benavidez’s childhood under Jim Crow, his military career during the Cold War as an elite member of a Special Forces reconnaissance team taking part in top-secret missions, his post-service life as a celebrated speaker who encouraged young people to stay out of trouble and serve their country, and his role as a veterans’ advocate who fundamentally changed the review process for disability benefits.

Sturkey also brings to light Benavidez’s ancestors who lost their 4,000-acre family ranch when Texas became a part of the United States, why one of his ancestors is known as the “Paul Revere of Texas” for the role he played in the Texas Revolution (a war in the 1830s that resulted in Texas’s independence from Mexico), and the little-known U.S. military missions in Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

“In my opinion, Hispanic Americans are still the most underrepresented group in our histories and media, even though they’re north of 20 percent of the population. There are millions of Hispanics who’ve lived here for more than a hundred years and have contributed to this country the whole time, and yet they’ve never received full access to citizenship benefits and belonging,” says Sturkey, who notes that Benavidez was so often praised for overcoming challenges without acknowledging the external forces that created them. “Hispanic Americans are such a huge part of the American story, and their experiences need to be centered more.”

As for The Ballad of Roy Benavidez: The Life and Times of America’s Most Famous Hispanic War Hero, Sturkey says he hopes readers take away a two-fold message: “Celebrating veterans is not enough and it is not the same thing as serving them,” he says. “And the story of an everyday working-class Hispanic American can help tell the story of the marginalized group of people from which he came…. Roy Benavidez was constantly telling people he was proud to be an American, but I always had the feeling that he was reminding them that he was an American, too.”