When Catherine Sorrentino, C’25, approached Kathleen Brown about studying the origins of the cadaver trade for her senior thesis project, it seemed to Brown a well thought out idea. As a scholar, Brown herself had written some about the subject, and, in her role as lead faculty historian of the Penn & Slavery Project, had advised other students on it as well.

“Though it wasn’t a new topic, Catherine’s approach was different,” says Brown, David Boies Professor of History. “She really wanted to connect the dots between this very elite medical school in Britain, where some of the earliest Philadelphia physicians had trained, to the practices that followed in Philadelphia.”

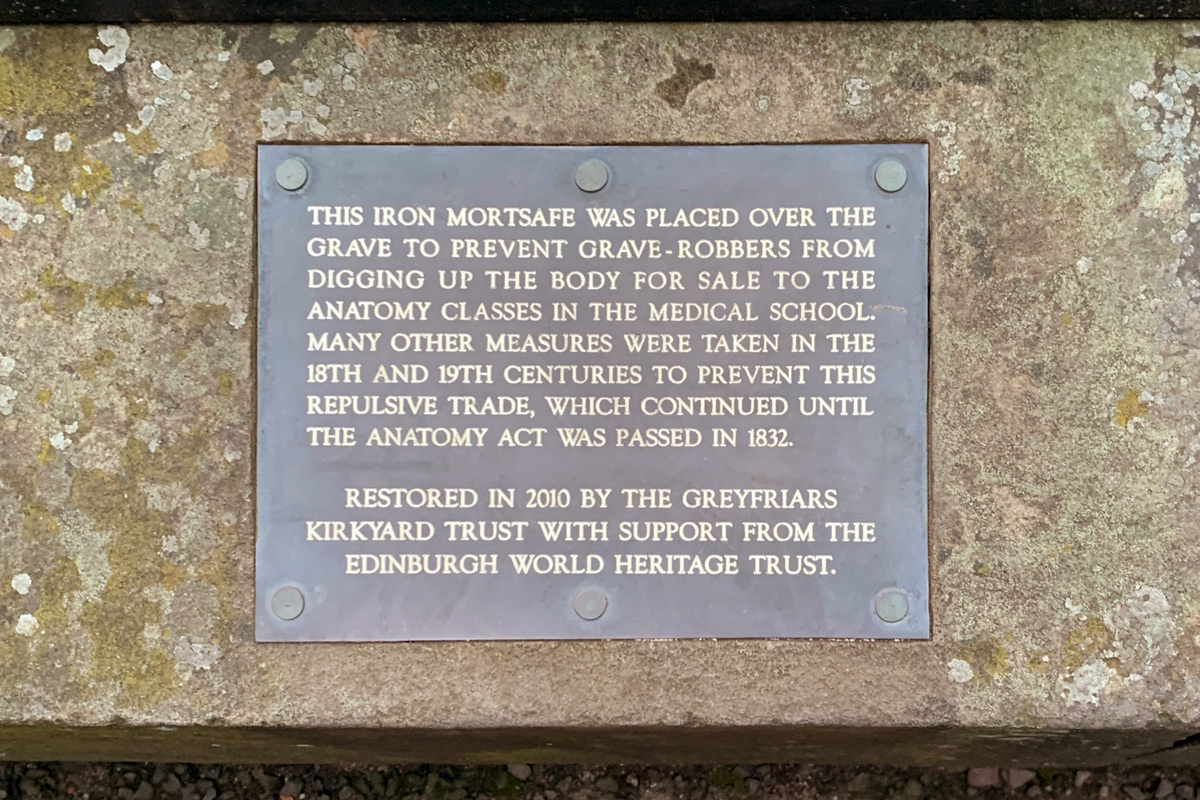

A plaque that Sorrentino came across during her time conducting research in Scotland. (Image Courtesy Catherine Sorrentino)

In Pennsylvania and during a week she spent at the University of Edinburgh, Sorrentino scoured medical student theses, record books, and minutes from medical department meetings, lecture notes, and any primary source material and archival documents she could find. The difficulty was, “people don’t really write about this because it wasn’t something you wanted to be public about doing,” she says.

In the end, however, Sorrentino was able to trace the practice of graverobbing for medical-education purposes from 18th-century Scotland to 19th-century Philadelphia. She found that as anatomical medicine rose as the preferred way to train new physicians, medical professionals in Edinburgh exploited society’s vulnerable to get the cadavers they needed. Physicians who had trained in Scotland then brought the practice back with them to Philadelphia.

The subject of the cadaver trade in medicine first came to Sorrentino’s attention in high school, when she wrote a paper about a famous doctor who went on trial in Great Britain for his relationship with graverobbers. As she started thinking about meaningful topics for her history thesis at Penn, she kept coming back to the history of medicine and medical care.

“I was thinking about different lenses and windows you can study a topic through,” she explains. “Also, the more I talked to people about graverobbing, doctors, and the rise of modern medicine, the more I realized people were interested in learning about it.”

Here, she offers some historical context: In the 18th century, doctors and intellectual institutions wanted to learn medicine in more biological terms, to look at real human bodies to study anatomy. At the time, this was a new facet of medical training. “When you look at a body, you’re not guessing anymore,” Sorrentino explains. “You have real knowledge of the body, and so doctors become more accurate, which makes them feel more professional, a bit more esteemed, more respectable.” This leads to greater interest in the field of medicine, which accelerates the demand for bodies to study.

Sorrentino used archival materials like this ledger to trace the practice of graverobbing from Edinburgh to Philadelphia. (Image: Courtesy Catherine Sorrentino)

Whereas a local government might have been able to meet the need of fewer medical students, “at some point, the government runs out of its capacity to secure cadavers,” Sorrentino says. “So, professors and their students decide to source their own.”

Brown notes that they generally took the path of least resistance, focusing on “really poor people and people whose bodies were vulnerable to being stolen after they died,” she says. In Scotland, that typically meant white people with little means, while in Philadelphia, it meant preying upon free Black communities.

Within these marginalized groups, Sorrentino adds, the cadaver trade generated significant social unrest and, in turn, action. In Edinburgh, she found evidence of churches that raised their walls to keep out “vandals and thieves,” and of townspeople rioting against anyone suspected of working with medical professionals to facilitate this.

Source material from Philadelphia showed free Black communities attempting to buy or lease the land for their graveyards to enable putting up walls and fences, though they were often unsuccessful. “In one instance, I found an account of an armed patrol guard keeping watch over Black graveyards and chasing down people trying to steal bodies,” Sorrentino says. “There was resistance to this predatory action, and if they couldn’t stop it altogether, they were focused on protecting their own people.”

By the end of the 19th century, stealing cadavers in Philadelphia became taboo after a major scandal broke in which graverobbers were found with the keys to an anatomy lab of a reputable institution in the city. The scandal led to a trial and eventually legislation from Pennsylvania about when, where, and how the state would provide the bodies needed for anatomical study.

Scandals led to public backlash and legislation intended to end the trade. I say ‘intended’ because just because these laws were passed doesn’t mean that downward trade necessarily died out.

“This happened in Europe, too,” Sorrentino says. “Scandals led to public backlash and legislation intended to end the trade. I say ‘intended’ because just because these laws were passed doesn’t mean that downward trade necessarily died out, and it didn’t necessarily change minds. This kind of behavior was still, I think, acceptable among doctors well into the 20th century.”

The recency of these crimes offers an important window into the pedagogy surrounding medical practices, the sourcing of cadavers, and modern medicine, Brown says. “Catherine is really a very talented researcher. She approached this as a pedagogical practice, and she had a sense that there was something to connect between Philadelphia and Edinburgh. We might have guessed at that connection, but actually finding it in the archives is another story.”

For her part, Sorrentino feels there’s more of this history to tell. She says perhaps she’ll return to it eventually, focusing on the relationship between medical students and graverobbers in Scotland.