Tweeting the Medieval

Emily Steiner, Professor of English, uses new technology to illuminate age-old manuscripts.

It began with a line from a medieval encyclopedia. Fewer than 140 characters typed into Twitter, it was an academic exercise to grapple with an overwhelmingly dense tome.

Emily Steiner, a professor of English, was deeply skeptical of the social media site. But late that night nearly three years ago as she struggled with research for a book, her husband, also a professor, suggested she tweet out a few quotes from the manuscript and review them in the morning, saying he suspected there was a scholarly audience on Twitter that might support her in her research and writing.

“I thought Twitter was the last thing I could ever be interested in,” recalls Steiner, a recognized expert in medieval studies.

But she gave it a try. On October 30, 2014, @PiersatPenn tweeted out a line in Middle English: “The little finger is called ‘auriculus’ or ‘ere fyngir’: ‘for with hym we clawen and piken the eres.’ #trevisaquotes” (The pinky is called the “ear finger” because “we claw and pick the ears with it.”)

It seemed to her incongruous to quote such an ancient text on such a modern platform. Who else in the Twittersphere would be interested in work by John Trevisa, an English translator of Latin encyclopedias and a late 14th-century contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer?

Turns out, lots of people, around the world. First a retired soldier-turned-priest living on a boat in Michigan who said he loved the Trevisa sentences. And a sheep herder outside of York, England. A knitter in California.

“They were my tiny audience for Trevisa. They would say “These lovely sentences get to me,’ Steiner remembers. “And I thought to myself, ‘what is it about this prose that Twitter captures so effectively? And then I realized it’s the syntax and cadence of the English prose that is so beautiful, and it resonates with us because it sounds so modern. This medieval encyclopedia is actually the precursor to modern literary prose.”

It took Twitter to make her slow down, she says, and see that Trevisa’s prose was rhymed, and sometimes alliterated, with a distinct and moving rhythm. “Until Twitter, I totally didn’t see it,” she says. “That was a major breakthrough in my research.”

From a late-night lark to what has become an integral part of her academic life, Twitter is a collaborative international forum where Steiner has discovered a unique voice to share her love of, and expertise in, all things medieval.

Picturing the Middle Ages

Steiner began to look at Twitter as a way to reach a larger audience. “I want people to love and understand the Middle Ages,” she says. “I wanted more public teaching, more conversations.”

As she added images, she got more followers. “Every time I put up a quotation I started to look for a medieval manuscript image to complement it. The project became much more about word and image. People are really invested in the visual.”

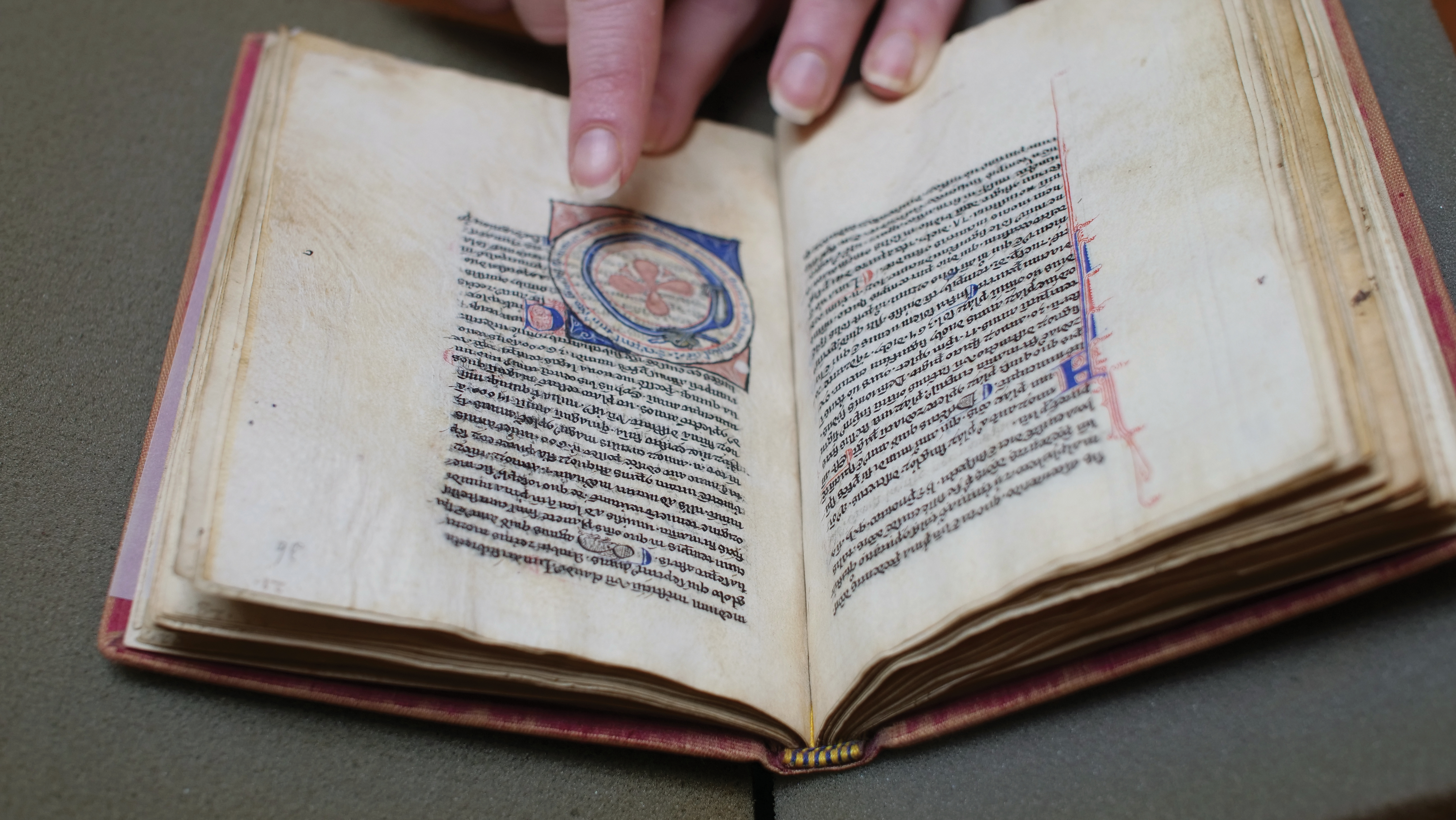

The images Steiner posts are deeply colorful and intricately drawn, often depicting scenes that tell a story. Some are from archives recently digitized, others from manuscripts deep in remote libraries. Each tweet is based in research and scholarship.

“I try to post images I think a lot of people haven’t seen or are unaware of,” she says.

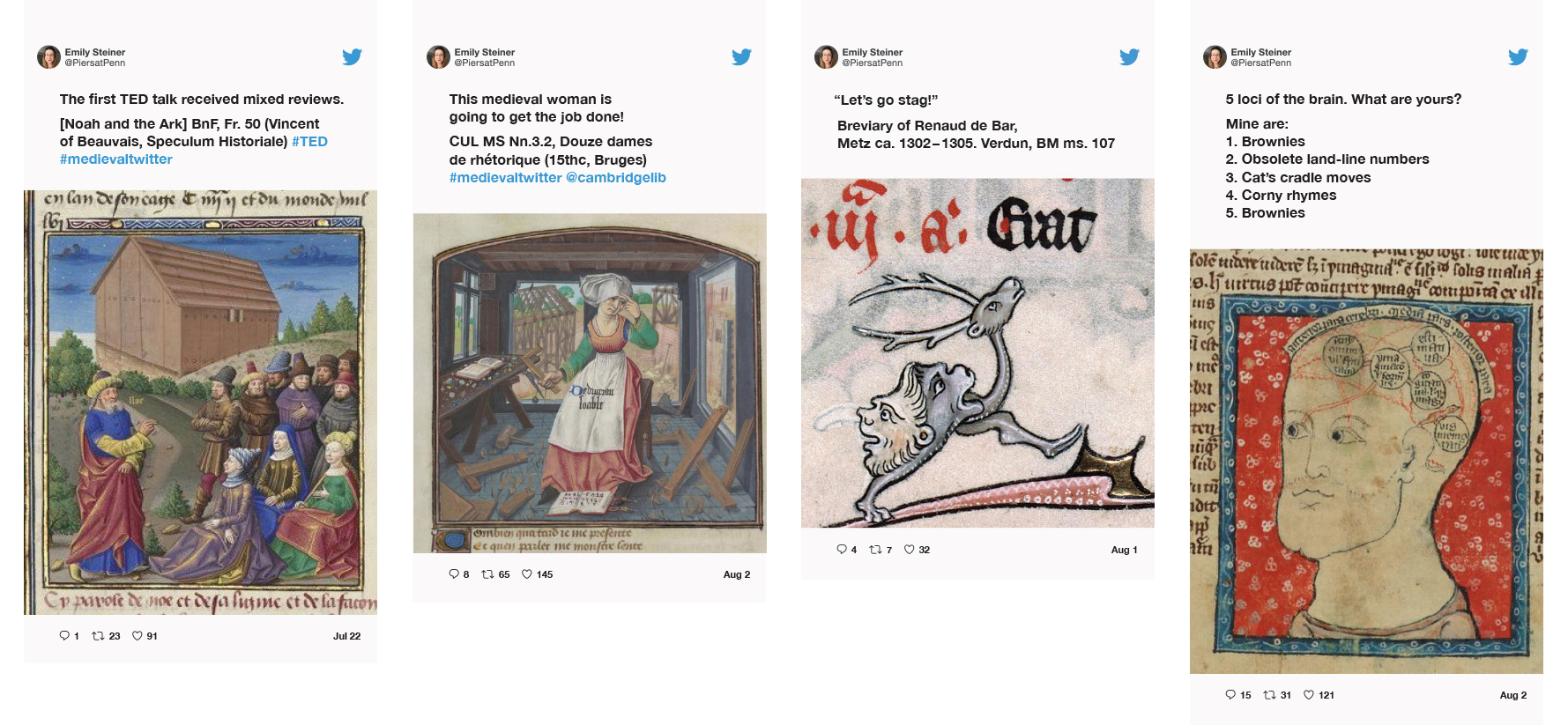

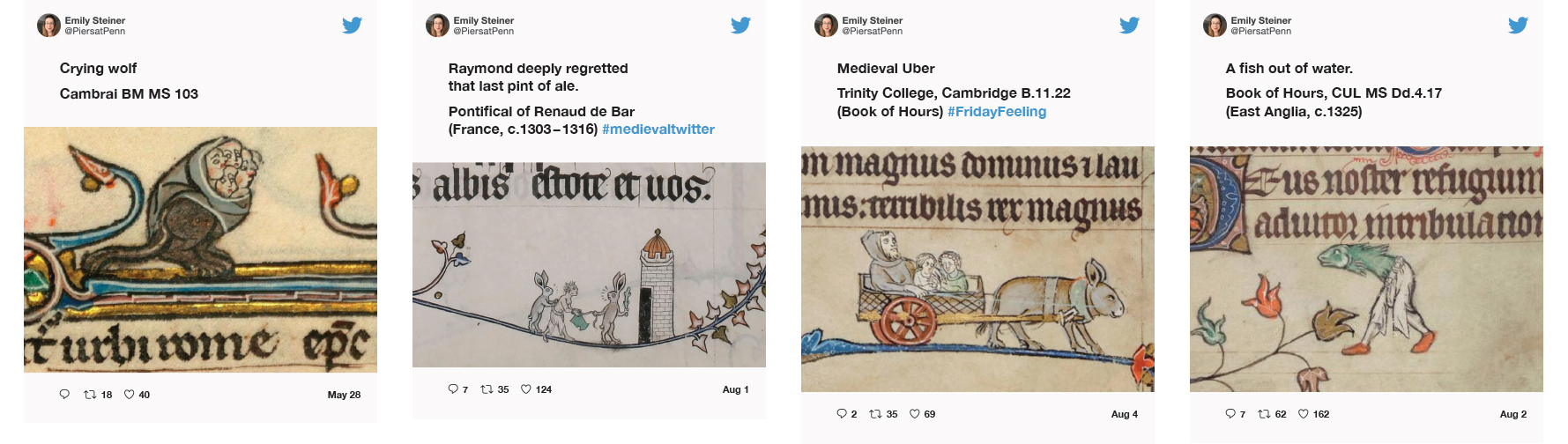

Steiner often makes comments, usually just a few well-chosen words or phrases, that reference popular culture.

“One thing Emily does really wonderfully is that she is able to take an image and communicate it with a pithy saying, connecting an abstract medieval image to the contemporary world,” says Mitch Fraas (@MitchFraas), curator at Penn Libraries’ Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts.

For example, a detailed drawing of two aristocratic women, one handing a soldier a severed head dripping bright red blood: “Sometimes you find the perfect gift.” Noah addressing a group of townspeople, ark in view: “The first TED talk received mixed reviews.” A dog-like creature staring at a deer with large antlers: “Nice rack.” A family in a cart, being pulled by a fantastical creature: “Medieval Uber.”

“What’s unique about Emily’s Twitter account is that it is both learned and hilarious,” says Paul Cobb, Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations (@cobbpasha), adding that Twitter is the perfect place for “serious fun.” “That’s why Emily’s Twitter account is so successful. She has a great Twitter personality.”

Now, Steiner’s Twitter account has about 9,000 followers. She has posted more than 7,000 tweets in the past three years, often several a day.

“I feel like this is this whole other part of my life,” she says. “It’s almost like a parallel universe.”

“There is a lot of knowledge being exchanged in a collaborative, international forum. From a scholarly perspective, it is just a tremendously rich community.”

– Emily Steiner, Professor of English

Curious Collaborations

Her Twitter universe is collaborative, diverse, and international. Half of her followers are in the U.K. More than three-quarters are college educated, and they are equal parts men and women.

Her tweets appeal to several distinct sectors. The animal lovers are passionate about any image with a creature. The knitters and calligraphers are drawn to the decorative borders and patterns. The Dungeons and Dragons crowd goes for anything with a knight or dragon. Many followers revel in the rich religious imagery. Other audiences include lovers of classical mythology, transgender advocates, and insomniacs.

“I follow my research and put out what is interesting to me,” Steiner says. “I always try to educate. If I post something that’s funny I always try to make sure that the attribution is right. Indirectly I’m also trying to teach my followers something they didn’t know about the Middle Ages and its relationship to contemporary life.”

While Steiner generally avoids talking about politics on Twitter, she sometimes uses tweets to comment on issues of importance to her.

“Sometimes I want to talk about what is going on now. Medieval images help me to talk about those things,” she says.

For example, she is passionate about the education of girls around the world. In an April tweet she posted a series of images showing Saint Anne educating her young daughter, Mary, taking her to school, book in hand, with the comment “Virgin Mary: reading, writing, loved. #girlscount #daughters #medievaltwitter.”

Many scholars—other lovers of the Middle Ages—from around the world follow Steiner’s Twitter account. She is thinking of them when she makes a find she suspects few have seen.

In what she believes is one of the first Middle Ages depictions of a sunrise, found in a 15th-century French encyclopedia, gold stars shine on a lightening blue sky, yellow on the horizon behind two hills. “Medievalists went crazy for that,” she says, noting 330 likes and 111 retweets. “There are very few pictures of the dawn, just like there are not many pictures of rain.”

According to Steiner, sharing information is very important in the world of online scholars.

“The medievalists on Twitter are very active, in archives, taking pictures, asking people to help them solve problems, sharing tidbits,” Steiner says. “There is a lot of knowledge being exchanged in a collaborative, international forum. From a scholarly perspective, it is just a tremendously rich community.”

Unique Voice

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (@JeffreyJCohen), Professor of English and Director of the Institute for Medieval and Early Modern Studies at George Washington University, says Steiner is a key contributor to the medievalist world on Twitter.

“Emily has an excellent eye and is great at combing archives and sharing such vivid images. She understands why these images speak to us today, and how they engage people,” Cohen says.

Consistently the posts are beautiful and optimistic, he says, even though many medieval images can be disturbing or even offensive.

“I like the positivity of what Emily disseminates as representation of the Middle Ages. I think it helps to challenge some of the myths about the period,” Cohen says. “Emily’s Twitter feed is so affirming. It makes me laugh and opens my eyes to what I like best about the study of the Middle Ages.”

He mentions her tweet of a 1425 illustration of a green globe suspended in blue, from the Vatican Library, with the comment “Lonely Planet.” “Emily reminded us that there was actually a medieval desire to see the round Earth as if suspended in space.”

“Marginalia” is ripe for hybrid creatures and grotesques, which are shorthand for communicating the “lighthearted and earthy, even rebellious” aspects of the Middle Ages.

– Emily Steiner, Professor of English

Scientific illustrations are some of Steiner’s favorites to post, using the #sciart hashtag. “What I look for are stylized pictures of the natural world,” she says, including depictions of the earth, the sun, the moon, the constellations, the zodiac, the creation of the planet, and recently, the solar eclipse.

For example, two illustrations of the earth by Johannes de Sacro Bosco in 1275, one created with thick lines of pink and blue paint, another drawn as a pink flower surrounded by rings, were tweeted with the comment: “Radically simplified worlds.”

She found those images in the Penn Libraries’ Schoenberg Center for Manuscript Studies. The Center and its online catalog of digitized, high-resolution images is a key source of inspiration for her posts.

Fraas of the Penn Libraries says he especially likes the illustrations Steiner finds in the margins of medieval texts. “A sheep in the margins of a manuscript, and the comment is inflected by her own interests and sense of humor,” he says.

The “marginalia” is ripe for hybrid creatures and grotesques, which are shorthand for communicating the “lighthearted and earthy, even rebellious” aspects of the Middle Ages, Steiner says.

“Medieval humor at its best when it shows vulnerable creatures taking control,” she notes. Rabbits hunting dogs, horse riding people, wolves in sheep’s clothing: all of these images reflect the medieval interest in portraying the social world inverted and turned upside down.

The drawings in margins are some of her favorites to tweet. “Bottom feeders,” with two fish doodled at the bottom of a manuscript from the 1320s: “Snail’s pace #amwriting” with a 13th-century, delicately drawn snail in red and blue. “Sometimes collaboration makes sense,” with a rabbit playing an organ and a dog working the bellows in a psalter from the 1330s.

Twitter as Academic Toolbox

The quotes and images that fill her Twitter archive come from a myriad of sources. She finds them in the original manuscripts in libraries. Or she pulls them from newly digitized archives, including the Vatican, the Getty, and the Schoenberg collection at Penn. Some treasures she finds in minutes, but others take her a long while, especially if she is looking for something specific.

“It can take a certain amount of patience,” she says, noting that the online archives can be challenging to use effectively. “There are big treasure troves of manuscripts, and if you can learn how to navigate the sites you can find things people haven’t looked at before.”

As a professor of English, Steiner is also interested in etymologies, and will post word origins, illustrations of libraries and studies, book bindings. One day she used the term “footloose and fancy free” and wondered.

She researched “footloose,” and along with an illustration of men in a sailboat, she tweeted: “The “foot” is the bottom of a sail: a sail that is footloose is free to move whichever way the wind blows.” Footloose has been one of her most popular tweets, with more than 800 likes and 350 retweets. “Merriam-Webster retweeted that one,” she remembers.

The archive she has created on Twitter has become a rich resource for her teaching. A Medieval English Drama course Steiner taught incorporated biblical plays that included the tradition of Mary as a prodigy, which she says the students found surprising. “Thanks to the images I collected for my Twitter posts, I was able to give them a mini-lecture on Mary’s education,” she says.

Steiner has been a professor at Penn for 18 years. She earned her Ph.D. in Medieval Studies from Yale University, and her undergraduate degree from Brown University. Her latest book, the one she was researching when she started tweeting the Trevisa quotes, is nearly complete: An Information Age: Literature and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Medieval England.

Going forward, Steiner is archiving her Twitter postings to make them a manageable tool, easily searchable. Twitter has become part of the fabric of her academic research, which she says relies on instinct, accident, and collaboration, all critical characteristics of this modern medium.

“I feel that Twitter is a different incarnation, but also an extension of my approach to research. That’s why I think this works well for me.”