Recovery and Rejuvenation

Penn’s Educational Partnerships with Indigenous Communities builds alliances with Native Americans to restore Indigenous knowledge systems and languages.

Language is an intrinsic part of culture and an essential way of sharing customs, knowledge, and belief systems. But in North America, Indigenous people historically were forced by the U.S. and Canadian governments to abandon their languages. Today, many Indigenous communities are engaging in a painstaking process of language recovery and rejuvenation. Penn’s Educational Partnerships with Indigenous Communities (EPIC) was created to support this effort.

Part of the Penn Language Center, EPIC was established through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) with a mission to share knowledge and resources with Indigenous communities while working to expand the number of Indigenous languages offered for instruction at the University. It was developed by the late Timothy Powell, a senior lecturer in religious studies.

“EPIC brings together language educators, curriculum developers, and scholars from Native American communities and the humanities at Penn,” says EPIC Director Christina Frei.

To date, EPIC has established working relationships with members of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, the Tuscarora Nation in New York, the M’Chigeeng First Nation (Ojibwe) on Manitoulin Island (Ontario), the Fond du Lac Band (Chippewa) in Wisconsin, the Six Nations Haudenosaunee in Ontario, and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in North Dakota. A two-day conference in April 2019, Indigenous Knowledge Systems: Revitalization, Resistance, and Regene- ration, provided the first opportunity for EPIC’s partners to come together on campus.

The headline speaker at last April’s conference was LaDonna Brave Bull Allard. A member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and a tribal historian, Brave Bull Allard founded the first resistance camp to the Dakota Access Pipeline on her family’s land along the Cannonball River in 2016. She spoke about waking each morning during the encampment to the sound of people singing and telling stories in dozens of Indigenous tongues: “None of them were speaking English—to me that was power.”

“That first meeting kicked things into motion, and we are now following up with a white paper for the NEH in which we will articulate our action plan for moving forward,” says Frei, who is also Executive Director of Language Instruction and Chair of the Penn Language Center. A second meeting planned for April 2020 will provide an opportunity to articulate specific tribal needs and identify common themes for the next NEH grant proposal—such as digital repatriation, land equity, professionalization, and establishing long-term alliances among the partners.

Associate Professor of Anthropology Margaret Bruchac says it’s significant that another speaker at the first EPIC conference was Curtis Zunigha, founder of the Lenape Center in New York City. The University sits on land once occupied by the Lenape people.

“It’s crucial for educational institutions like Penn to not only acknowledge who these people are—whose territory this is and what the history is—but to also find ways to bring them into the contemporary conversation,” she says. Bruchac coordinates Penn’s Native American and Indigenous Studies Initiative and is a consultant to EPIC; the American Section at the Penn Museum; and the American Philosophical Society (APS), based in Philadelphia. A member of the Abenaki tribe, Bruchac was awarded tenure this year, making her the first tenured Native American faculty member at Penn Arts & Sciences—Frei sees this appointment as a strong signal of the University’s commitment to Native American and Indigenous Studies.

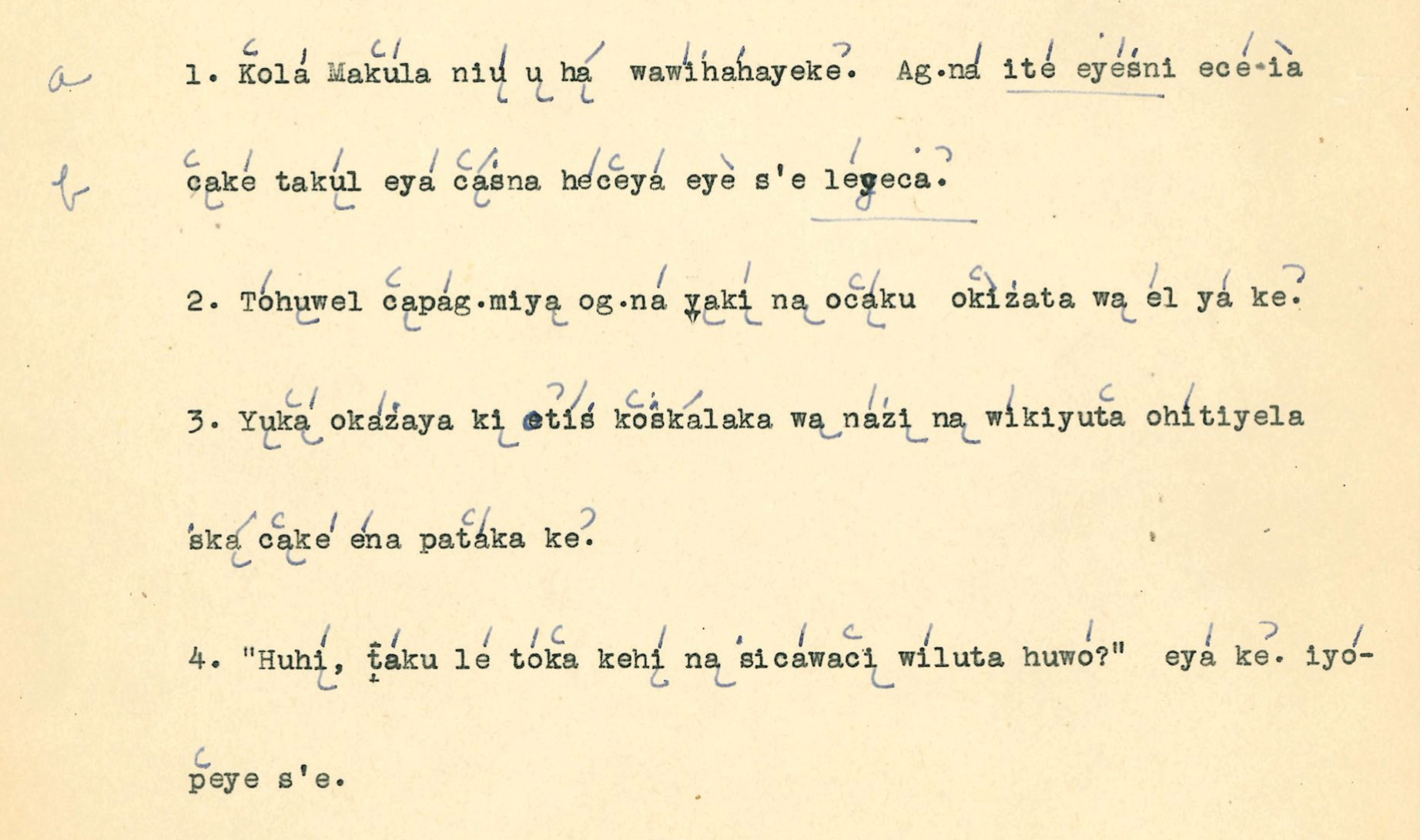

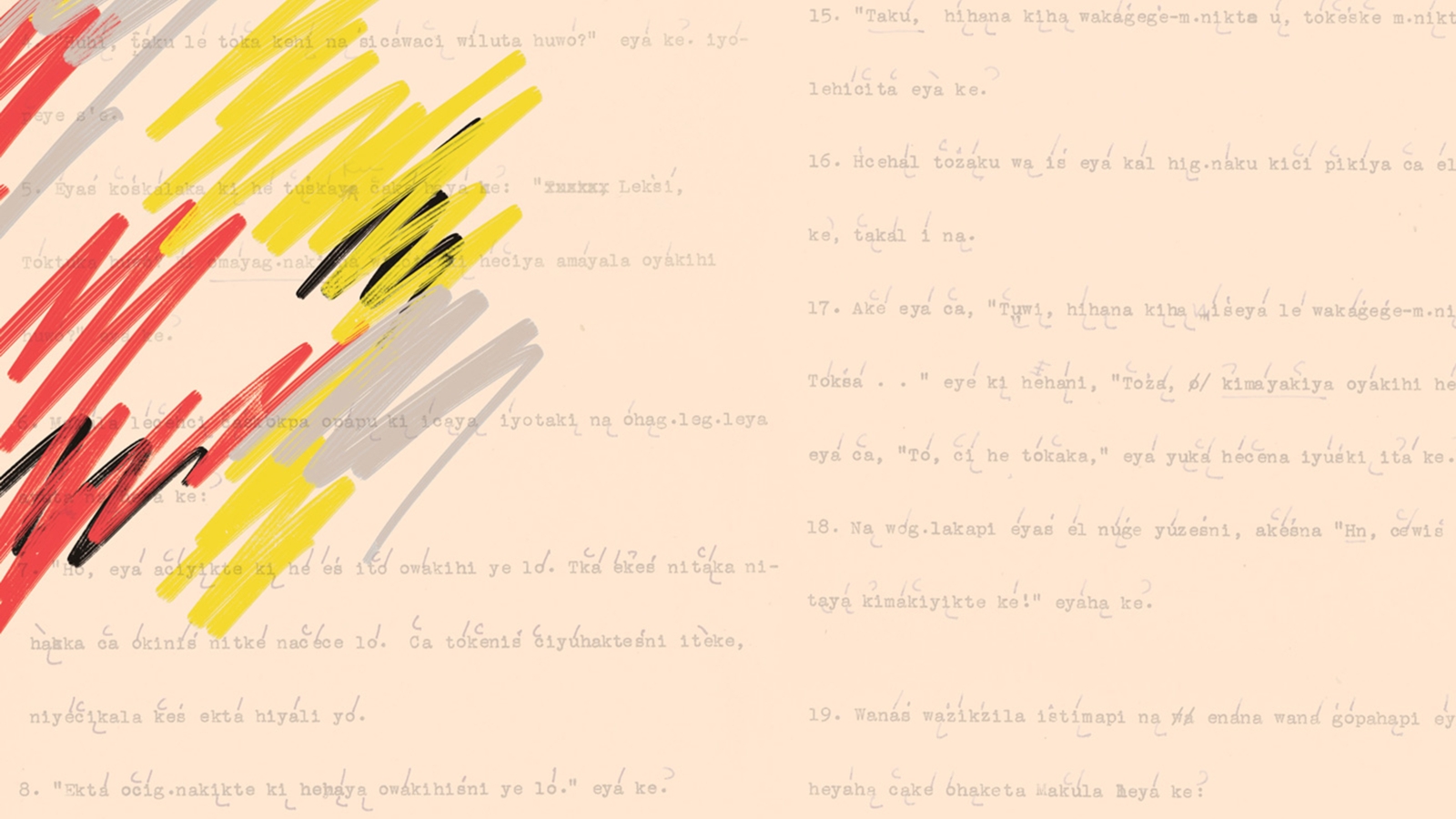

A key component of the EPIC initiative is digital repatriation—the scanning and digitizing of materials such as recordings and transcriptions of language so they can be easily shared with Indigenous communities. This is something that Powell had been deeply involved in through his longtime association with APS.

“The APS is the largest resource for our tribal partners, with a comprehensive archive of Indigenous language collections,” Frei notes. “For many of our partners, particularly the Cherokee and the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, there are not that many fluent speakers of the languages left.”

The Penn Museum is a vital resource for Indigenous people and an essential partner for EPIC. Stephanie Mach, a doctoral student in museum anthropology, a member of the Navajo Nation, and part of the Museum’s Academic Engagement staff, says, “EPIC is essentially about ensuring access to Indigenous people’s own heritage. The overall goal is cultural revitalization, knowledge recovery, and regeneration, and the materials stewarded by the Museum are an integral part of that process. I appreciate knowing that Penn supports Indigenous communities in this way.”

Frei and Bruchac see EPIC as a vehicle for long-term, equitable collaborations between Penn and Indigenous communities.

“The University could facilitate access to materials at APS and objects in the Penn Museum, and resources in the Language Center or other departments, so that it can be a real back-and-forth,” says Bruchac. She also envisions an interdisciplinary course encompassing history, anthropology, folklore, and education that engages Indigenous language experts.

“Through these encounters, we could find ways to create residencies for Indigenous scholars who might want to do research here at Penn,” she says. “Picture inviting an elder who runs language recovery in his or her community to come here for a week or two, do research at APS and the Museum, teach and meet with faculty and students, and then go back to their communities renewed with information they can use for their own educational, cultural, or linguistic purposes.”

Frei notes that the Penn Language Center has the flexibility to appoint language instructors to teach Indigenous American languages, provided there is demonstrated interest on the part of at least five students. Currently, Penn offers instruction in Quechua—the most widely spoken Indigenous language of South America—but no North American languages; Frei says Lenape would make sense as a starting point.

We want to approach this partnership based on what our partners need. To build trust and ask how Penn can facilitate their needs, as well as recognize the knowledge they have to share about critical issues such as climate change.

“I think what I’m most proud of, as far as continuing Tim Powell’s legacy, is that EPIC is starting a process of healing,” says Frei. “We want to approach this partnership based on what our partners need. To build trust and ask how the University of Pennsylvania can facilitate their needs, as well as recognize the knowledge they have to share about critical issues such as climate change.”

“We want to help ensure that the public becomes more aware of the survivance and visibility of multiple and richly diverse Native Nations,” adds Bruchac, “each with its own distinctive history and deserving of understanding on its own terms.”

A Legacy of Reciprocity

The elements of recovery and reciprocity were of paramount importance for EPIC founder, the late Timothy Powell. In a 2016 article for Museum Anthropology Review, he recalled learning about “community-based scholarship” from Richard Hill, then-Director of the Deyhahá:ge: Indigenous Knowledge Center at Six Nations Polytechnic in Ontario. Powell wrote: “The success of community-based scholarship depends on reimagining the relationship between the academic knowledge systems and the knowledge systems maintained by traditional knowledge keepers and community members who are working to pass the teachings on to the next generation. The goal is to foster a new, sustainable relationship whereby educators in both systems respect the validity of each other’s knowledge in order to craft mutually beneficial partnerships to improve the quality of education in both systems.”