Life Advice from Aristotle

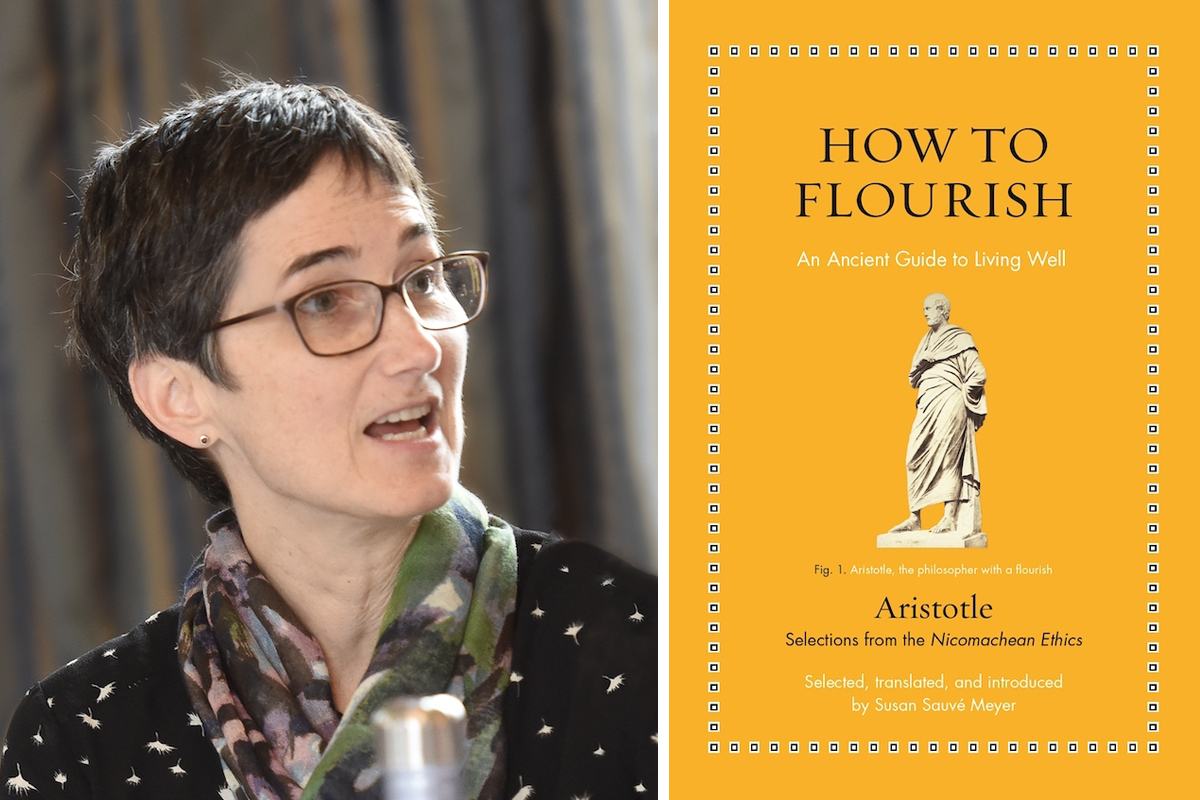

A new book by Philosophy’s Susan Sauvé Meyer gives tips from the philosopher’s “Nicomachean Ethics” on how to live well in any age.

The title How to Flourish sounds like any other self-help book—until you see the subtitle, An Ancient Guide to Living Well. The bright yellow book turns out to be an abridged version of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, translated by and with additional commentary by Susan Sauvé Meyer, Professor of Philosophy.

What can a dead man from ancient Greece tell us about how to live well in a world with the internet, nuclear weapons, climate threats, and fast food? Sections within the book with headings like “Justice,” “Fun and Games,” “Personal Finance,” “Anger Management,” and so on, show that Aristotle does indeed have something to say about issues we currently face.

“‘Flourish’ is a big buzzword now, and it’s how some translate eudaimonia, the key term in Aristotle’s Ethics,” says Meyer. “The big question in ethics, with Aristotle and before him Plato, is what is happiness? What do we want to do? We want to live well, so ethics is all about the question, ‘What is it to live well?’”

A More Accessible Aristotle

Aristotle was born in what is now Macedonia in 384 B.C.E. When he was 17, he went to Athens, the center of culture and intellect in the Western world at that time, and spent 20 years at Plato’s Academy. Then he traveled and conducted biological research, tutored the future Alexander the Great, and returned to Athens to found his own school, the Lyceum. He wrote about ethics, politics, poetics, literary criticism, rhetoric, logic, zoology. “He was an intellectual omnivore,” says Meyer.

Unfortunately, the writing that Aristotle published during his lifetime is lost, and what we do have is the work he didn’t polish for publication, possibly notes for lectures, Meyer says. “We know his writings were well regarded in antiquity. Even Cicero thought he had a ‘golden flow’ of words. But what remains are terse and often crabbed in style. So only a philosopher can love reading Aristotle.” Ethics is also very long, and of course, in ancient Greek.

Enter the Princeton University Press’s Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers book series, which produces public-facing translations aimed at the general reader. During the pandemic, a Press editor called up Meyer to discuss the project. “I said, ‘Sure, I’ll talk to anybody, I’m bored out of my skull here,’” she recalls. “I thought the chance to translate Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, it’s sort of like a chance to play in Carnegie Hall. I’ve done a lot of my own work on the Nicomachean Ethics. I’ve taught it a lot. I know it.”

Of course, any translation is about making the work accessible. “You read it, you figure it out, and then you have to communicate, render it in English,” says Meyer. “Then you decide, what do you preserve?”

Meyer used the sections she has students read when she teaches the book as the basis for her abridgement. She also added commentary to help the reader along, including notes about the more severely abridged sections and expanding on different understandings of words and concepts between Aristotle’s time and ours. (For the especially curious or erudite, the book also includes the ancient Greek text.)

A Short Guide to a Good Life, with Some Caveats

Aristotle opens by discussing the goal of life, and continues into his views on building character, our responsibilities, and the approaches he recommends. Meyer identifies Aristotle’s central question as “What makes for a flourishing life—one where we realize our full potential as rational, emotional, and social beings?” She says Aristotle wants us to use to the fullest the capacities we have that are distinctively human—feeling and reasoning—to care about the right things and act for the right reasons. We do this through virtues of character and intellect.

“‘Virtue’ is an archaic term. It’s really hard to use it without putting scare quotes around it,” says Meyer. “The way I understand Aristotle is, you’re living up to the standards for a human being, not aiming at the highest salary or the most followers or the Nobel Prize. You’re acting in a way that a human being could be proud of.”

The way I understand Aristotle is, you’re living up to the standards for a human being, not aiming at the highest salary or the most followers or the Nobel Prize. You’re acting in a way that a human being could be proud of.

Within the larger chapters (which are called books), Meyer finds writing that applies to specific challenges and issues for both ancient and modern people, and highlights them in sections like “Fun and Games” and “Personal Finance.” She wrote an essay for the book’s website about how we can use what Aristotle says about social interactions with social media.

To show broader application of Aristotle’s writing, Meyer cites the work of colleague Sukaina Hirji, an assistant professor of philosophy whose research includes Aristotle’s ethics as well as theories of oppression and contemporary philosophy. To live Aristotle’s “good life,” people need to have the liberty to exercise their intellect and decision-making, Meyer says, explaining that Hirji and others have “found that Aristotle is actually a really good theorist if you want to talk about oppression, because oppression is something that keeps you from being able to do something.”

But some of his beliefs and ideas are outdated or offensive, she adds. “He’s a good target to disagree with on some things. He thought that women couldn’t do philosophy,” says Meyer. “But he built the bridge and we can walk over it.”

Public-Facing Philosophy

For several years Meyer has been working to make philosophy more accessible. She created two Coursera courses, Plato and his Predecessors and Aristotle and his Successors, which are free and open to the public. She got a hit of publicity early in the pandemic when Shakira posted on then-Twitter about taking the Plato course. Now How to Flourish has been written about in The New Yorker. “I thought, are you kidding? Aristotle’s Ethics!” Meyer says.

Ultimately the book is a guide to the importance of balancing the life of the mind, which Aristotle regards in almost religious terms, according to Meyer, with a life of engaging and interacting with others. “And you can’t do them at the same time,” she points out. “You have to find space in your life for both.”

When it comes down to it, Aristotle is trying to make sense of human life. “You have to be willing to think about it and think for yourself, and you have to slow down enough to try and follow him along,” Meyer says.