A Pandemic Puzzle

This summer, Matthew Breier, C’26, worked with Associate Professor David Barnes to research how the 1918 flu pandemic affected Philadelphia’s Black and immigrant neighborhoods.

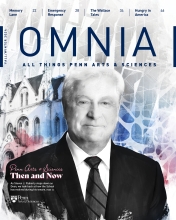

Matthew Breier, C’26, flipping through Philadelphia’s 1918 city directory.

Matthew Breier, C’26, spent his summer immersed in primary sources like death certificates and Philadelphia’s 1918 city directory to learn about the effect of the 1918 influenza pandemic on Black and immigrant neighborhoods, part of a project led by public health historian David Barnes, an associate professor in the Department of History and Sociology of Science.

“It’s mind-boggling how little we know about this thing that happened during the age of scientific medicine, during the age of mass media,” Barnes says.

Specifically, Barnes wanted to understand whether certain populations were more vulnerable to dying from the flu in 1918, part of a broader question he had about whether people in the past experienced chronic stress. When Breier came on through the Penn Undergraduate Research Mentoring Program, he was tasked with mapping where people who died from influenza lived, as well as learning more about the characteristics of neighborhoods with high and low mortality rates.

To do this, he scoured death certificates. He took trips to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center. He made observations—deaths in African-American communities seemed to be less commonly reported than deaths of European immigrants, for instance—and learned how to interpret what he read.

“If you see two people with the same last name listed right next to each other and they died a day or two apart, or even on the same day, you can imagine that they were a mother and her child or a husband and wife,” says Breier, who is double majoring in anthropology and health and societies with minors in classical studies and history. “It brings this research to life.”

The experience, he adds, was “incredibly valuable,” an opportunity to receive one-on-one mentorship for work in a department he cares about deeply and an introduction to how research in the humanities works. “To understand the full picture of the period and event we are examining,” Breier says, “we must interact with and examine both quantitative and qualitative data and documents.”