OMNIA Q&A: The Winners and Losers in Post-Socialist Europe

Kristen Ghodsee and Mitchell Orenstein, professors of Russian and East European Studies, discuss their new book, Taking Stock of Shock.

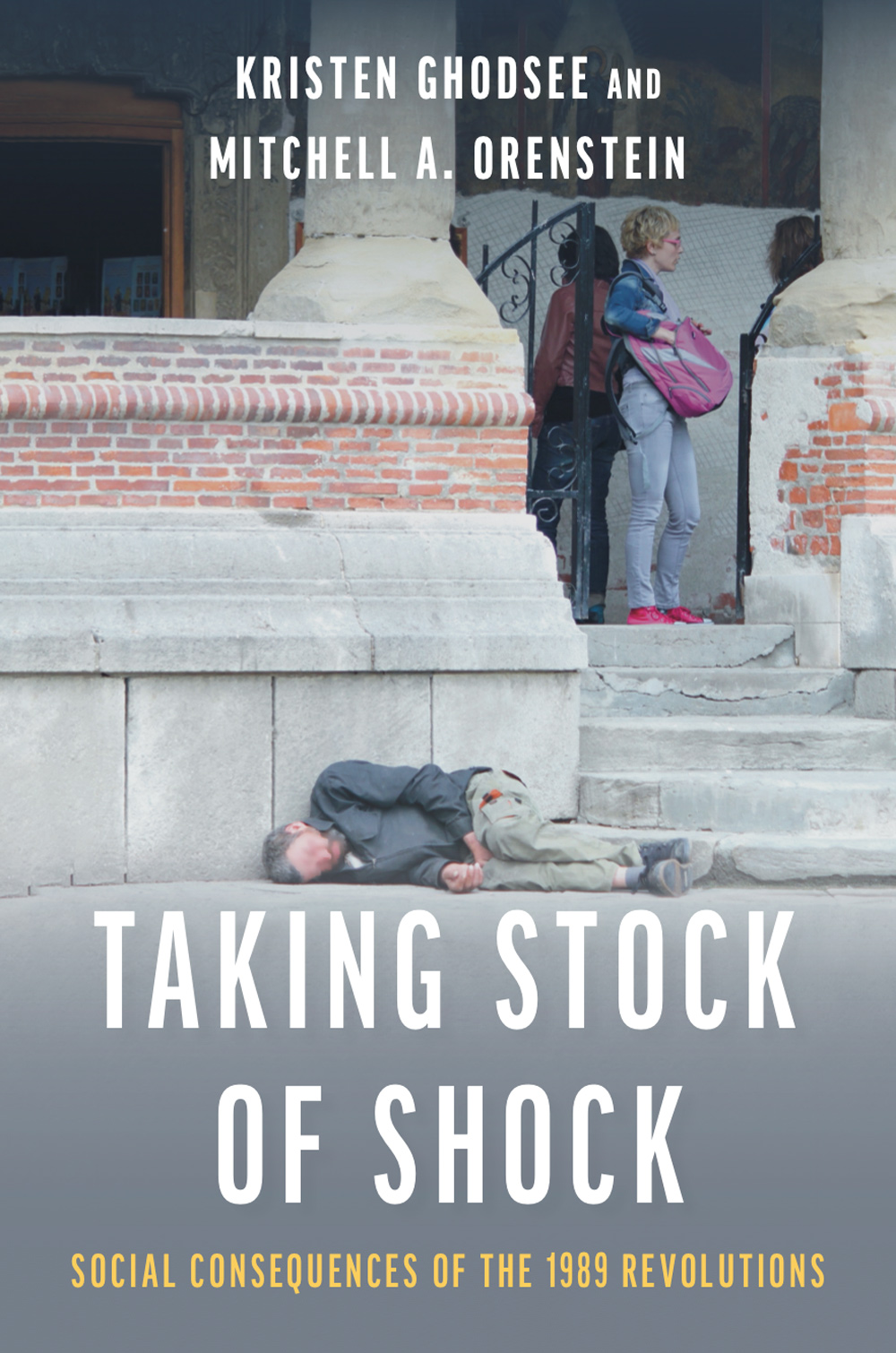

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell unexpectedly, which led to a wave of revolutions across Eastern Europe, culminating with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Suddenly, more than 400 million people were living in post-Socialist states. The summer after the Wall fell, Kristen Ghodsee and Mitchell Orenstein were traveling separately in Eastern Europe. Unbeknownst to them at the time, that experience would help shape their careers. Both now professors of Russian and East European Studies, Ghodsee and Orenstein recently co-authored a book, Taking Stock of Shock: Social Consequences of the 1989 Revolutions, which provides an interdisciplinary look at 29 countries over the last 30 years of transition.

How did this book come to fruition?

Ghodsee: It started with a disagreement. Mitchell’s early work focused on Czechia and Poland, while my work focused more on Bulgaria and the Balkans. He’s a political scientist; I'm an ethnographer. We held very different views about the impact of the changes in 1989 in the region.

Orenstein: Kristen sent me an article by Branko Milanović [a Serbian-American economist] that was really interesting and provocative. Basically, he argued that people hadn't benefited economically from the revolutions of 1989. His ideas didn’t align with my own observations of certain countries. On the other hand, Kristen thought he was underestimating how bad things really were.

Why did you title the book Taking Stock of Shock?

Ghodsee: In economics, the phrase “shock therapy” refers to a series of policies related to rapid privatization, rapid price liberalization, and the rapid dismantling of the social safety nets under state socialism. All three of those policies were recommended by market fundamentalists in the West who thought that the only way to build vibrant capitalist economies was to destroy every last vestige of communism immediately. However, they did this before they even built the institutions necessary for capitalism to function. Those shock therapy policies are precisely what caused the most deleterious effects in the region. Measured by the decline in GDP, most of the countries in Eastern Europe suffered longer and deeper depressions than America’s Great Depression in the 1930s.

What did the research process look like?

Ghodsee: Rather than just look at economic data like GDP per capita or average consumption, which is what most people who study the transition focus on, we decided to combine that with public opinion, demographic, and ethnographic data to show a more robust picture of what’s happened over the last 30 years. Bulgaria is a great example. If you focus only on indicators like GDP per capita, it looks like Bulgaria is doing well. You could look at contemporary Bulgaria and say that the transition has been good for most people, while in fact, public opinion surveys show that many people are nostalgic for their lives under communism and that most feel they're worse off than they were before 1989. The country also has the fastest-shrinking population in the world. It’s expected to lose an additional 23 percent of its population by 2050. Young people are leaving, fertility is declining, and basically nobody wants to live there, which is a total catastrophe for the country.

Orenstein: We believed that if we could gather a more complete data set from a number of different fields and areas and move beyond just economic indicators, we could come to a clear understanding. Somebody would be right, and somebody would be wrong.

Was somebody right and somebody wrong?

Orenstein: Honestly, what we found was quite surprising for both of us. As we went further into the research and gathered data with the help of a Penn undergraduate research assistant, Nicholas Emery [C’18, now a Ph.D. student at UCLA], we found both of our stories were right.

Ghodsee: Yes, our key finding is that the transition was really good for some people and really bad for others.

Orenstein: I would estimate approximately one third of the people in the post-socialist space did really well, for instance in Poland and the Czech Republic. A lot of people experienced improved living standards and life satisfaction, had more opportunities, and enjoyed being able to travel abroad. While we also found that some countries, on average, have not come back to where they were in 1989.

Some countries have done better than other countries, but it's also more complicated than that because even within countries, some regions did better than others. For example, a lot of capital cities or cities that have strong foreign investment are doing extremely well, while not that far away, other areas are doing absolutely terribly. Generally, younger people and the highly educated did well, but there was a massive increase in inequality after socialism ended. Huge new opportunities existed, but not for everybody.

What went wrong?

Ghodsee: Eastern European countries were supposed to be democracies in the sense that they were supposed to vote for their leaders who would then choose social and economic policies that reflected the will of their constituencies—that's how functional democracies work. What actually happened in many of these countries is that either the EU, the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, or the IMF made all the decisions and Eastern European populations had very little say in the kinds of economic policies that were enacted.

Orenstein: The transition was one of the biggest disasters in Europe, demographically and economically, since the Second World War. It's comparable in scope to one of the big wars or revolutions in terms of the number of people who died or were impoverished. Our book shows that as much as half the population in the entire region were living in poverty at one point. This raises important questions about the type of economic reform that was done, about the Western-influenced shock therapy idea that things would bounce back quickly if you just let markets manage themselves. In our book, we contrast that approach with China’s, which is not a perfect comparison because China didn't democratize but it did transform its socialist economy into a capitalist one with massive economic growth over roughly the same time period. And it did so without the life expectancy and demographic disasters that occurred in Eastern Europe. Looking at things from a bird's-eye view, some might reasonably conclude that the Chinese route was better. I think that's very unfortunate for Europe, for the people in these countries, and frankly, for advocates of democracy and capitalism.

What could have been done differently?

Orenstein: The economist Jeffrey Sachs really thought that we should have had a kind of Marshall Plan for Eastern Europe to help ease the transition. That idea may have been financially untenable but there probably should have been a universalization of social benefits, knowing that there was going to be a lot of economic pain for a lot of people.

Ghodsee: We have good data that shows that populations in countries that privatized more slowly, that invested in active labor market policies, and that maintained social safety nets, did not suffer as badly as countries that jumped into capitalism. In my opinion, a slower, more deliberate transition to capitalism would have been better.

What’s the state of Eastern Europe today?

Orenstein: In the region right now, there's a struggle between the broad forces of liberalism and populism in which people appreciate democracy and freedom but they don't appreciate the kind of disastrous economic policies that ruined a lot of people's lives needlessly. And while they may respect capitalism, they don't want an unbridled capitalism that doesn't provide for people.

Ghodsee: Most of the fastest-shrinking countries in the world are in Eastern Europe, and there is also a strong and growing presence of virulent right wing nationalist parties. Look at Russia, Poland, or Hungary, for example, who are embracing what has been called illiberal democracy, which is when countries have elections, but those elections are manipulated so there is the veneer of democracy rather than the substance. We may be potentially dealing with a renewed Cold War, partially because of the legitimate frustrations of people in this part of the world. I think that we ignore Eastern Europe at our peril because these are countries who have suffered a lot, and in the case of Russia, still have a lot of nuclear weapons.