OMNIA Q&A: Beyond the Bodies

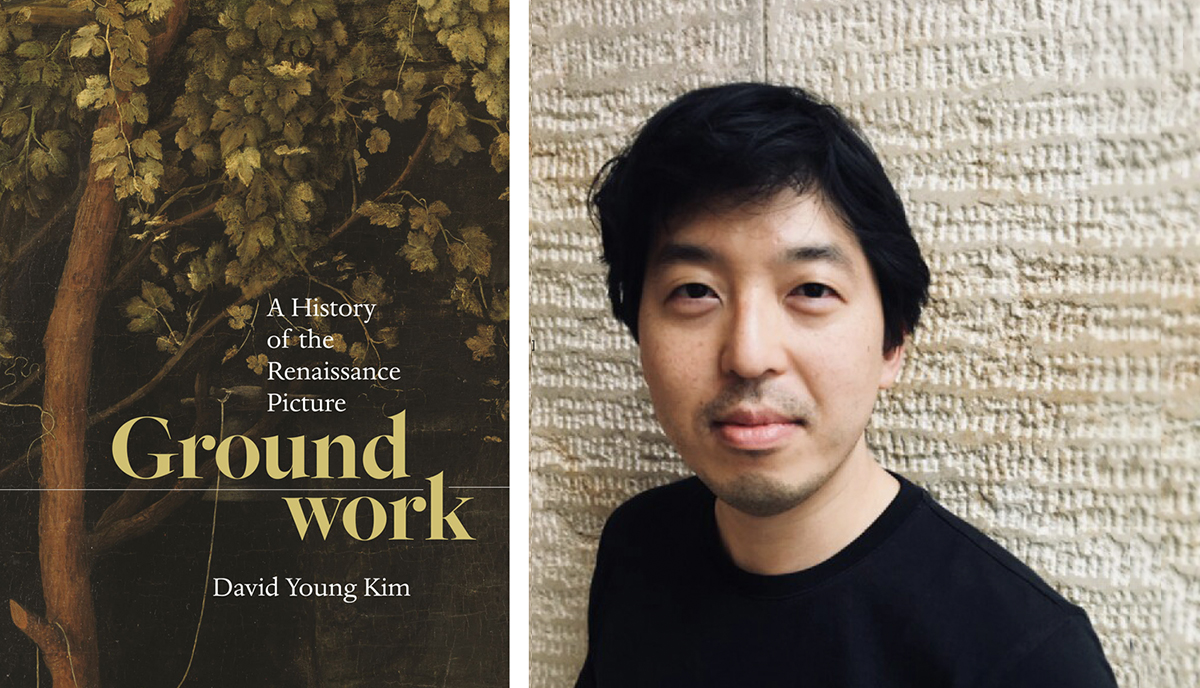

David Young Kim, Associate Professor of History of Art, encourages art historians and enthusiasts to look beyond the figures in Renaissance art to notice the richness of the groundwork.

David Young Kim, Associate Professor in the History of Art, studies Italian Renaissance art, a period that he says has always been preoccupied with “bodies, bodies, bodies.” In his new book, Groundwork: A History of the Renaissance Picture, he challenges the assumption that bodies are the only sites of meaning in Renaissance art and takes a slower, closer look at the meaning of what’s behind, beneath, above, and around the human figures. Groundwork is the first in-depth examination of the complex relationship between figure and ground in Renaissance painting, with the ground referring to the preparation of a work’s surface, the fictive floor or plane, or the background on which figuration occurs.

Here, we speak with Kim about his inspiration for the book, the significance of ground forms in Renaissance paintings, and how his viewpoint is shaped by his Korean-American identity.

Why did you choose to write a book on this particular topic?

In the art period that I study, which is the Renaissance, you just see bodies, bodies, bodies. It's a type of art that is really preoccupied with the figure. At least, that's what I thought at first. However, if you look beyond the figure, there's so much going on around the figure, below the figure, next to the figure, but art historians don't pay attention to that. They assume that the figure is the primary vehicle of meaning and interpretation. But in teaching at Penn, students would ask, "Professor Kim, what's actually happening next to the figure, behind the figure, or underneath the figure?" I would think, "I don't really know." I sort of wrote the book to address the perceptions of the students who, I think, have a different and more holistic view of the art than I was trained to have when I was a student.

What were some of your major findings on the significance of these ground forms?

At Penn, we have several students who are enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. So, because I'm not an artist myself, I would ask them, "What do you think is happening in this painting?" One student responded, “For me, what's most interesting is what's happening before the painting seems to emerge." Artists actually spend a lot of time thinking about the composition even before they draw the figure. For example, preparing the canvas, laying down the ground, laying the second layer of ground, laying down gold ground—all this stuff before the supposed major part of the painting comes into being. That is actually a fundamental part of the artistic process. And so, what the student said was that art historians look at the figure first and the ground second, but artists look at the ground first and think about the figure second. I just thought that reversal of art history’s priorities was really exciting to explore and a bit of a paradigm shift.

Why do you think the complex relationship between figure and ground in Renaissance painting has been largely overlooked?

I think it's because human beings fixate upon human beings. When we actually go through the world, we encounter the world through our bodies, and we look for other bodies as sites of meaning. Also, we often don't realize that those bodies in the world are actually dependent upon placement and space. It's an obvious thing, but it's often easy to overlook. I think that because I don't come from a typical American background, I never really feel comfortable anywhere, to be honest. When I look at someone, I'm thinking not about who they are, but how do they locate themselves in space? For me, that's the way I encounter the world. I think that that's why I sort of have that weird perception of things.

What do you most want readers to take away from this book?

The first thing I want readers to do is go to the museum and look at works of Renaissance art in person—not only on the screen, as important as that experience can be—and actually look at the entire picture, not just what seems to be important at first glance. The more time you spend with these paintings, the more that emerges, comes to the fore, and grabs your attention—not just the figure, but that which is around the figure. It really creates a more holistic, richer, and maybe even deeper experience, not only of the painting, but also of your own experience of looking at the painting. That is to say, by spending more time in front of the painting, you yourself are aware of certain perceptual capabilities that you may not necessarily have been aware that you had.

Looking back at all these Caravaggios and Fabrianos, was there a particular piece that took on a new resonance or meaning for you?

It would have to be Giovanni Bellini's St. Francis in the Desert, because it's a painting that demands not only to be looked at, but to take you on a journey through the painting. We tend to think of looking at art as something we do in a single glance. But what's interesting and what I'm trying to do in the book is to think about looking not as a single instance, but through many, many different instances to actually think about looking at art on a multi-temporal scale, rather than simply from one moment to the next.

I think that with St. Francis in the Desert, we tend to think of the desert as a place of emptiness, as a place of non-life. But when Giovanni Bellini was painting the desert, he was actually really interested in the desert as a site of a lot of potential: potential for life and potential for meaning and potential for a relationship with the divine.

Who do you imagine picking up this book? Who's your ideal reader?

Obviously, I hope that lots of people read it. But when I think of readers, I reflect on growing up in a family in which my mother's English is such that she may not necessarily be able to read scholarly prose in English, but she can get a sense of the argument of the book from the images within it. Because what I've tried to do in the book is use the power of the details to actually bring to the reader or viewer realizations like, "Oh my gosh, I never noticed this detail in the background of this painting.” So, perhaps my ideal reader is actually an ideal viewer. Hopefully, people will grasp the argument of the book from images. But it’s written for anyone—from the scholar to people who are just generally interested in art. I’ve learned that, in teaching, you can never take enough time with a painting. And so, I guess what I wanted to do in the book is translate that experience of taking time with a painting within a classroom into book form. I also made a film that's related to the book with the purpose of using cinema to recreate, again, this idea of slow looking and close looking.

Are you working on a new project?

Yes, I'm writing a new book about a 20th century translation of Giorgio Vasari and more generally, the role of biography in art history and for the art historian. Vasari was the first art historian. He published his book, The Lives of the Artists, in 1550 and 1568. It was translated into Korean in 1986. My new book is about what it means to actually think about art history across languages, how the Italian Renaissance can be transported into different geographic areas, and what it means when it is encountered by or understood in a different geographic area by transnational readers and thinkers.