OMNIA Q&A: 2,800 Years of Ideas

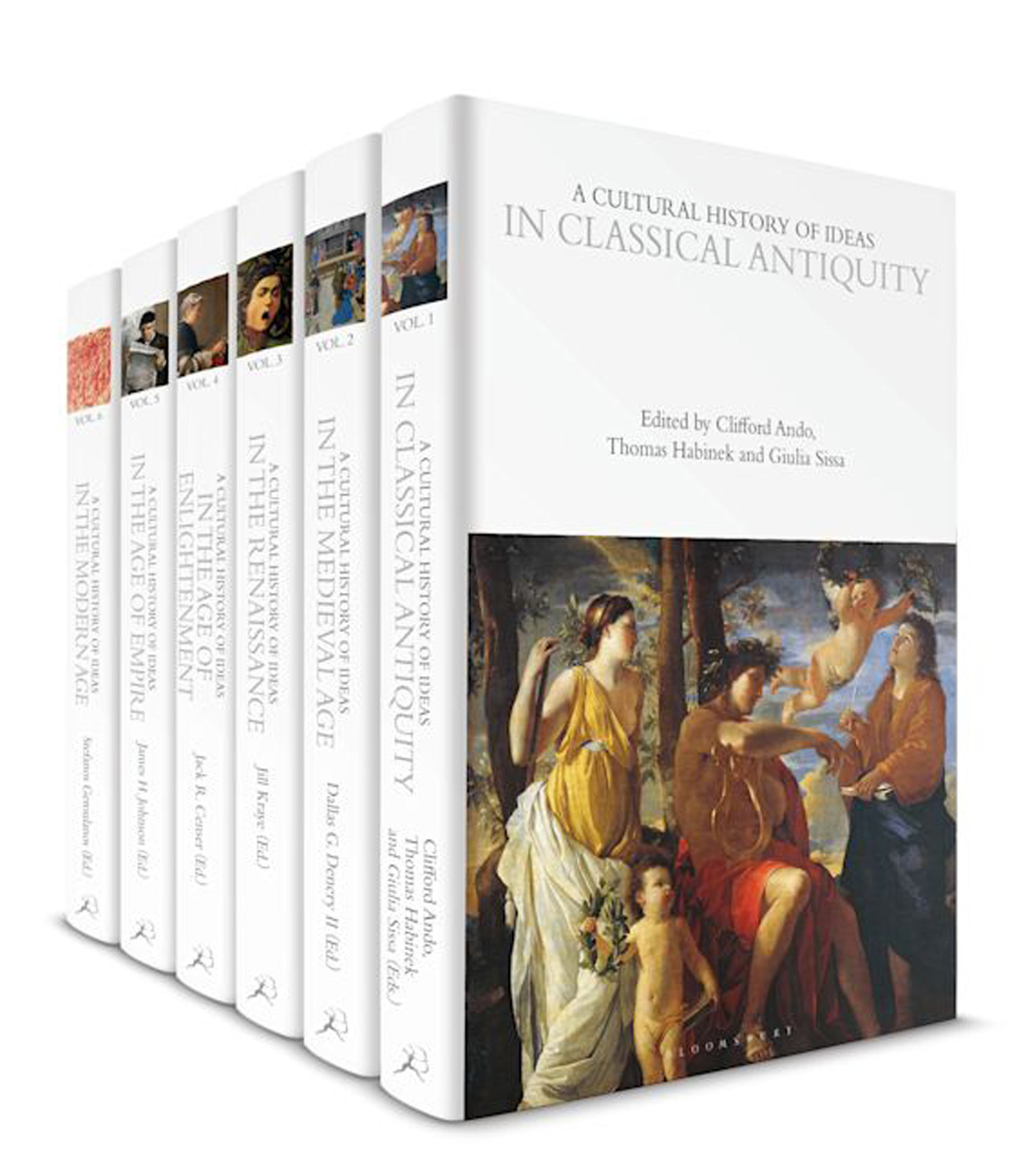

Sophia Rosenfeld, Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History, and Peter Struck, Professor of Classical Studies, discuss their new book series, A Cultural History of Ideas.

How do you capture the nature of ideas over the course of 2,800 years? How do you adequately convey how each distinct time period and social, political, and cultural context shaped the development of those ideas?

These are the weighty questions that Sophia Rosenfeld and Peter Struck set out to answer as coeditors of a new series, A Cultural History of Ideas. The series features 62 expert contributors across six volumes covering Classical Antiquity, the Medieval Age, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, the Age of Empire, and the Modern Age. Each volume has identical chapter titles and themes that cohesively organize the series across volumes: Knowledge; the Human Self; Ethics and Social Relations; Politics and Economies; Nature; Religion and the Divine; Language, Poetry, and Rhetoric; the Arts; and History.

Here, we speak with Rosenfeld, Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History, and Struck, Professor of Classical Studies, about why they were eager to take on this massive undertaking, how people might approach the series in a variety of ways, and what they most hope readers will take way from the volumes.

How did you both become editors of this series?

Rosenfeld: The English publisher Bloomsbury has many series called A Cultural History of... So, our project is not the first such series, but I was approached by the publisher and asked, “Did I want to do a cultural history of ideas?” That’s a big idea in and of itself. My first thought was that I couldn’t possibly do this by myself. The only way I could possibly imagine doing this is if Peter Struck did it with me.

Struck: When Sophia came to me with the idea, I was delighted, but we both asked each other, “Is it crazy to think about doing almost 3,000 years of intellectual history in a coherent way—in a way that's going to contribute something new to our field?”

Rosenfeld: The scale of the project was enormous. We're talking six books, but within the six books, a whole series of sub-editors of different volumes, and then in every volume, multiple articles. None of us has the expertise to easily think about several thousand years of intellectual history and cultural history across a range of topics. But I knew that with Peter, who has a remarkable range over antiquity—Greek and Roman—and through the medieval and Renaissance period, I could dovetail my knowledge of the Renaissance onwards. Much to my luck, Peter agreed.

You knew this was going to be a herculean undertaking, yet you agreed to take it on. Why?

Rosenfeld: The first major challenge was coming up with categories that would make equal sense whether we were talking about Athens in the ancient period or Western Europe in the 1950s. Would concepts like nature, the divine, the arts, or even the self, make sense across those moments? Some of our most interesting conversations were trying to figure out categories that would be loose enough, but also meaningful enough, to work across this whole 2,800-year period. Another challenge was thinking about the right contributors. Who was doing interesting work that would allow us not to write a history of the famous thinkers lined up in a row, but rather to proceed much more in the vein of the cultural history of ideas, considering how ideas emerged, how they were put into practice, and how they were adopted and remade over time.

Struck: For me, the opportunity to contribute to a new perspective in the field was the most exciting piece. Part of what we're doing here is to claim that ideas don't just float around in space as prepackaged, little quanta of thinking that bounce around from place to place. They're produced in particular social contexts for particular reasons, and that means that there's a distinct way each age and each culture constructs knowledge for itself.

How should people to approach this series?

Rosenfeld: I don't think most people are going to read all six volumes article by article. That seems like a daunting task. But we hope they will be tempted to read these volumes and the chapters within them in a variety of different ways, including by topic or by period. We also hope different readers will take different things from them. A student might find a particular essay useful as a supplement or part of a class syllabus, or a researcher might read a chapter for background on a subject they are working on, or a general interest reader, who just wants to know something more about a particular topic, the arts in the 18th century, say, could very profitably do that. And some people will read our methodological introduction and be interested in the case we're making for a particular way of doing intellectual history that's not the way everybody in the field does it. And others will probably be less interested in the methodological piece and want to read more of the juicy content from our authors. Our ideal reader is any smart, engaged person who just wants to think about some of the big questions about where our ideas come from and how they operate in the world.

What do you hope readers will take away from the series?

Struck: My hope is that the broad view of history continues to inform work in the history of ideas. The aim of doing justice to the particularities of periods and cultures was a key intellectual driver in the humanities of the second half of the 20th century. While really important, that kind of thinking can make scholars reluctant to think broadly. But broad thinking opens unique insights, not in order to valorize some timeless wisdom (and I’m not even sure there is such a thing as timeless wisdom) but in providing a perspective that allows us to see how different times and places, including our own, produce their intellectual worlds.

Rosenfeld: In the best case, when you read good history, it makes you feel differently about the world in which you live right now and about your own surroundings. My real ambition for these essays and for the volumes as a whole would be that they leave the reader thinking differently about the past but also, as a result of estrangement, about the contemporary and the familiar. What did it mean to think about religion in a world that doesn't resemble our religious landscape? Or what did it mean to think about rhetoric and speech in a world that doesn't treat speech the way we do? And what conditions are responsible for these differences? My hope is that the reader will come back to the present and think, “Hm, the assumptions that I've made about my world are also really culturally embedded and specific; they're not universals, but they're particular to my own time and place and susceptible to change too.”