My VIPER Summer

Students and professors in the Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research spent the summer in the lab.

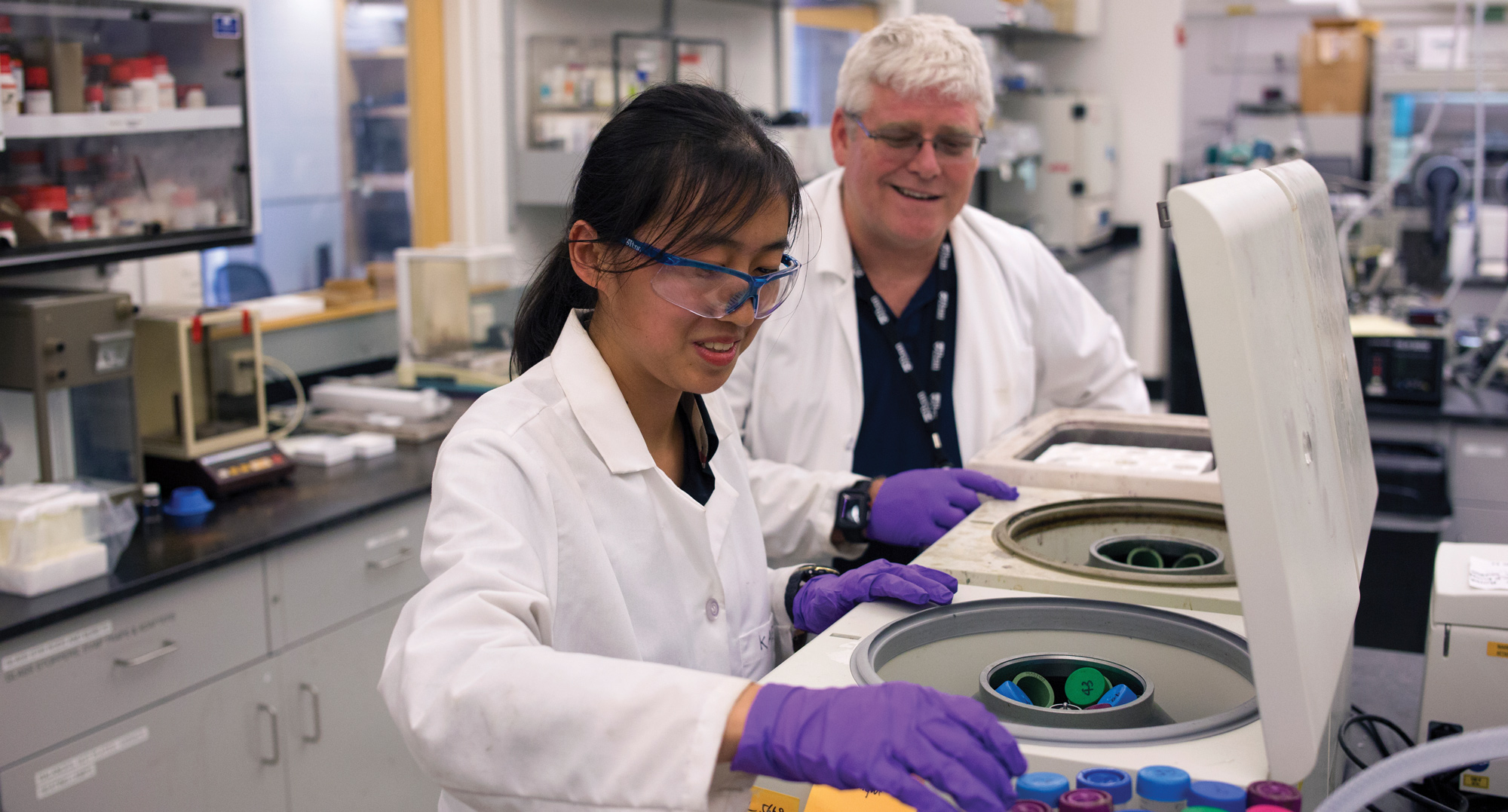

Karen Goldberg, Vagelos Professor in Energy Research in the Department of Chemistry and Director of the Vagelos Institute for Energy Science and Technology, and Bernie Wang, C’21, E’21

“I still want to know what your middle school science projects were,” says Karen Goldberg, Director of the Vagelos Institute for Energy Science and Technology, to Bernie Wang.

“The first year I was shooting lasers through Jell-O, pretty much,” answers Wang, C’21, E’21. “The next year, I found a biofuel project where you soaked chunks of cotton rope in oils.”

You don’t often get to hear an undergraduate chat about his seventh-grade science project with an internationally known researcher, but Wang has been collaborating with Goldberg, who is also Vagelos Professor in Energy Research in the Department of Chemistry, for almost two years. This mentorship is just one part of how the Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research (VIPER) gives its students graduate-level experience by the time they earn their undergraduate degree.

VIPER is a small and select cohort of students committed to solving the energy problems the world faces. They all complete two majors, one in Penn Arts & Sciences and one in Penn Engineering, so they can look at problems from both a scientific and a technological perspective. And they all spend the summer after their first year in a professor’s lab, beginning their research related to energy resilience.

“The idea is that they engage with state-of-the-art research as soon as possible,” says Andrew M. Rappe, Blanchard Professor of Chemistry, Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, and VIPER Faculty Co-Director.

John Vohs, Carl V.S. Patterson Professor of Chemical Engineering and the other Co-Director of VIPER, also notes that, “This early research experience allows them to become integral members of a research group while still an undergraduate. Many VIPER students have published papers on their research in prominent scientific journals by the time they graduate.” Wang, for example, was an author on an article published this fall.

The students continue to do lab research throughout their undergraduate careers, learning how to deal with the challenges of investigation and to write and present scientific information for different audiences. In Goldberg’s lab, Wang is helping to design a multi-catalyst system to convert carbon dioxide and hydrogen to methanol. Using three catalysts instead of just one allows them to optimize each step individually, improving the overall yield.

Both Kate Jiang, C’22, E’22, and Luka Yancopoulos, C’21, E’21, are conducting research at the sub-atomic level. Jiang is working with Christopher Murray, Richard Perry University Professor of Chemistry and Materials Science and Engineering, to use atoms and molecules to build new types of materials that can convert light to other types of energy. In the lab of Marija Drndić, Fay R. and Eugene L. Langberg Professor of Physics, Yancopoulos is fabricating nanopores, tiny holes which can measure DNA or other materials. It’s very fundamental research, but membranes with these pores could be used for energy storage or water filtration.

With Deep Jariwala, Assistant Professor of Electrical and Systems Engineering, Natalia Acero, C’21, E’21, is exploring how thin photovoltaic-like structures can be, down to just five or 10 atoms. A possible use: solar cells to power devices where weight is important, like in outer space.

Often, one of the first things students learn in the lab is what can go wrong. Acero says, “At the beginning you’re very surprised at how common it is for things to actually not work out, or that you’re working on something for months and suddenly think, ‘You need to drop this.’ But it’s also a huge motivator.”

“There may be some interaction that is unpredicted, but you discover you can use it for your benefit or you get an idea how to turn it into a useful thing,” says Drndić. “Everything is science, basically, even a negative.”

Throughout the summer, the VIPER students meet weekly for lunch. “We have students from all different major combinations, from physics and chemical engineering to earth science and bioengineering, and all kinds of researchers,” says Jiang. “It’s just great. By listening to their presentations and asking them questions, I get to know more than just what I’m working on.”

The bond the students form with their professors, lab mates, and classmates may be as big an advantage as the technical knowledge they acquire. “I’ve absolutely gained the confidence of knowing I can be given a new topic and I can understand it because of my mentors in the lab,” says Yancopoulos, who is conducting his own research project.

The professors welcome the undergraduates’ fresh outlooks. “VIPER undergraduates have unique perspectives because they are looking at the basic science side as well as the applied side, and they ask questions that get you thinking in a new direction,” says Engineering’s Jariwala.

I’ve absolutely gained the confidence of knowing I can be given a new topic and I can understand it because of my mentors in the lab.

By the end of the summer, says VIPER Co-Director Rappe, the students will have new questions that will drive them to get further knowledge in the classroom, and that fuels their interest to return to the lab.

Perry University Professor Murray adds, “By the time students have spent a couple of summers on a project they really are operating on the level of our graduate population. And then it’s just a joy.”