A Monumental View of the Ten Commandments

Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures Assistant Professor Timothy Hogue sees the foundational text as more than just words.

When Timothy Hogue started working on a book about the Ten Commandments, the ACLU had recently sued to prevent their display at two courthouses in Kentucky. This summer the commandments made news again, as Oklahoma and Louisiana sought to pass laws requiring all public schools to post them.

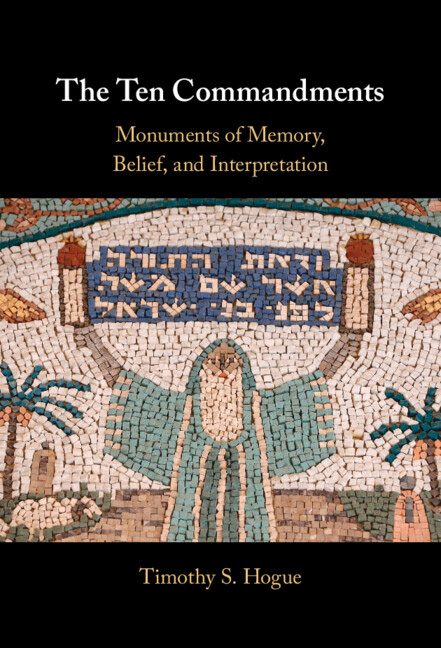

In his new book The Ten Commandments: Monuments of Memory, Belief, and Interpretation, Hogue argues that instances like these are just the latest in a history of the Ten Commandments as a monument, rather than just text, with the goal—then and now—of defining a community.

He makes his case by comparing their words, presentation, and how people interact with them in the Biblical narrative to other monuments of that time. “What are they written on?” he asks. “Where are they placed? What are the ritual or political practices of engaging with them? And how did all those aspects change over time?”

Hogue is an assistant professor of Middle Eastern languages and cultures whose specialty is the Hebrew Bible and ancient Israel. His field of study is the Levant, the area now occupied by Syria, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, and Jordan. Roughly 3,500 years ago, he reports, a new type of monument appeared there, designed to embody a king or other elite and create a community around that person. By the Iron Age, when scholars believe the Bible started to be written, it was the region’s most popular monument form. Their text began with the words “I am,” then identified a person, their deeds, and the behavior incumbent on followers because of those deeds.

“It was kings, or in some instances, queens, presenting themselves to a group of people and laying out their expectations about what they were to believe and how they should act,” Hogue says. “And that formed the community.” He points out that although it’s often left out of public versions of the Ten Commandments, in the Bible they begin with “I am Yahweh, your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of slavery.” The commandments themselves, then, were the behaviors intended to define how followers should act.

Through his research, Hogue discovered that such monuments evolved in text, style, and placement, depending on the social or political concerns of the times. He points to the fact that the Ten Commandments appear in the Bible twice—one of the few repeated texts. “In Exodus, the commandments are set up with an altar and stelae on a mountain, and the entire community is gathering around it,” Hogue says. “Then in Deuteronomy, suddenly it’s on tablets that get hidden in a box, and there’s much more social stratification, with the people getting at it via the priests and the Levites. That matches other historical changes happening in the region.”

Here he refers to a period starting about 3,000 years ago, when the Levant was in flux after the Bronze Age collapse of all the area’s superpowers, leaving political instability. People, including the Israelites, were trying to create new communities. “But even there it’s shifting over time,” says Hogue. “They’re trying to figure out how to draw those boundaries.” In the ninth and eight centuries BCE, he adds, “the kingdom gets destroyed, but the identity survives, and they’re trying to figure it out again. The Ten Commandments are produced to try to answer these questions.”

When Timothy Hogue started working on a book about the Ten Commandments, the ACLU had recently sued to prevent their display at two courthouses in Kentucky. This summer the commandments made news again, as Oklahoma and Louisiana sought to pass laws requiring all public schools to post them.

Take the directive to remember the Sabbath. In the Exodus version, followers are to do so because God created the world in six days and then rested. In Deuteronomy, it’s because the Israelites were enslaved in Egypt, and they must keep the Sabbath to let their own servants rest in the same way they are given rest. “It moves from this high-level theological reason into a much more practical, I would even say social justice-minded, one,” Hogue says.

It’s also important that the commandments are first seen at Sinai, which was understood by both Israelites and Egyptians as just beyond the border of Egypt. “They’ve passed outside of that political domain,” Hogue says. “By setting up the monument on the edge, it implies there should be another one somewhere else. Then Deuteronomy fulfills that promise.”

Hogue believes such modifications were instrumental in the longevity of the Ten Commandments. “There were intense efforts to maintain its monumentality. They updated the text. They moved it to the next stage. It starts getting put onto small artifacts that you can carry with you on necklaces. And once these communities are purely religious, there’s a stronger impetus to preserve it. Multiple communities coalesced around it, trying to update its relevance and preserving it in the process.”