How does one share knowledge and love of the medieval with the world in just 60 seconds? For English professor Emily Steiner, the answer was to put on a performance in front of Benjamin Franklin and College Hall, featuring some of her favorite Middle English words.

The idea for the performance was a response to the challenge to give a “60-Second Lecture,” an event series sponsored by the School of Arts and Sciences. On Wednesdays at noon in the spring and fall, invited faculty speak for a minute about their research. At select events, like graduation and homecoming, alumni and students also present. In the 15-year history of the series, Steiner’s was the first truly dramatic performance.

“I had to find a way to get people back into the Middle Ages very quickly,” she says. “What I actually had to do was make the Middle Ages come to them and pop into the present.”

And the best way to “pop,” she decided, was to put on a play. “I was going to have to call upon the great medieval tradition of outdoor drama if I was going to be able to do this effectively,” says Steiner, who also teaches a course at Penn on medieval drama.

Steiner’s lecture, she decided, would teach a few obsolete words that were popular six-hundred years ago. But choosing those words, she knew, would present a challenge. So she opened the debate to the public through Twitter, where her account @PiersatPenn has 14,000 followers and she often posts using the hashtag #medievaltwitter.

Steiner also realized she would needed a collaborator. She quickly recruited Aylin Malcolm, who was among the first who responded on Twitter.

Malcolm, a third-year Ph.D. student in English, suggested wlonk, her favorite medieval word “because of the tension between how it sounds and what it means, which is something really beautiful, or someone very noble and proud and physically appealing.”

The #medievaltwitter crowd was leaning more toward the gutter. “Chaucer's English has a lot of really naughty words,” Steiner says, “but we were trying to keep it clean. Although those are the ones people really wanted us to do.”

Initially, the goal was five words. But as they crafted the performance, 11 words were required to create a story with “just enough sparkle and spunk,” making every one of those 60 seconds count, Steiner says. They chose to write a narrative about elections, because of the approaching midterms and the fact that the topic gave them license to choose insulting words, of which Middle English has plenty. Their performance centers around two voters debating various candidates with medieval names.

“We had to pick words that kind of fell in together,” says Steiner. “We also wanted to call upon the ability of medieval English words to make you experience the sensation that they're describing.”

One of those was snurten, which they used with the “sense of turning your nose up, being really scornful.”

The topic Jangler is one, which means someone talks too much, in an unsophisticated way. “A babbler, or a chatterer,” Malcolm says. And, perhaps, doff, which refers to “idiots who use speech idiotically,” Steiner says.

Steiner and Malcom were thoughtful about the candidate names they chose. Steiner has conducted extensive research in medieval law in the 19 years she has taught at Penn. Reviewing her work, they chose names of real people who lived in the Middle Ages, through poll tax records from the 14th century. Surnames then often reflected character or profession or location, she says, like the character named Wynkyn-atte-Wall, who probably lived near a wall. Names also reflected characteristics or traits. For instance, a common medieval nickname is Hende, which means courteous and noble.

Other words were not common— kankerdort, for example, which means to be in a muddle, and hodir-modir, a rare word which means a secret--and they found only one sure textual record of it.

However, nesche, they discovered through Twitter, is still used in northern England, and Newfoundland. “I love this word because it means both ‘physically squishy,’ like brains or a jellyfish, but also someone who is a pushover and weak,” Steiner says. Similarly, bolken, to puke or belch, is obsolete in standard English, but a version, “boak” is still used today in Scottish slang.

During the performance, the 11 words, hand-lettered in bright-colored marker on four white posters, drew in curious passers-by from Locust Walk. Gestures were also important in trying to convey the meanings, for example pretending to dig with the word swinken, which means to toil or to work, as, for example, in an effort to get votes.

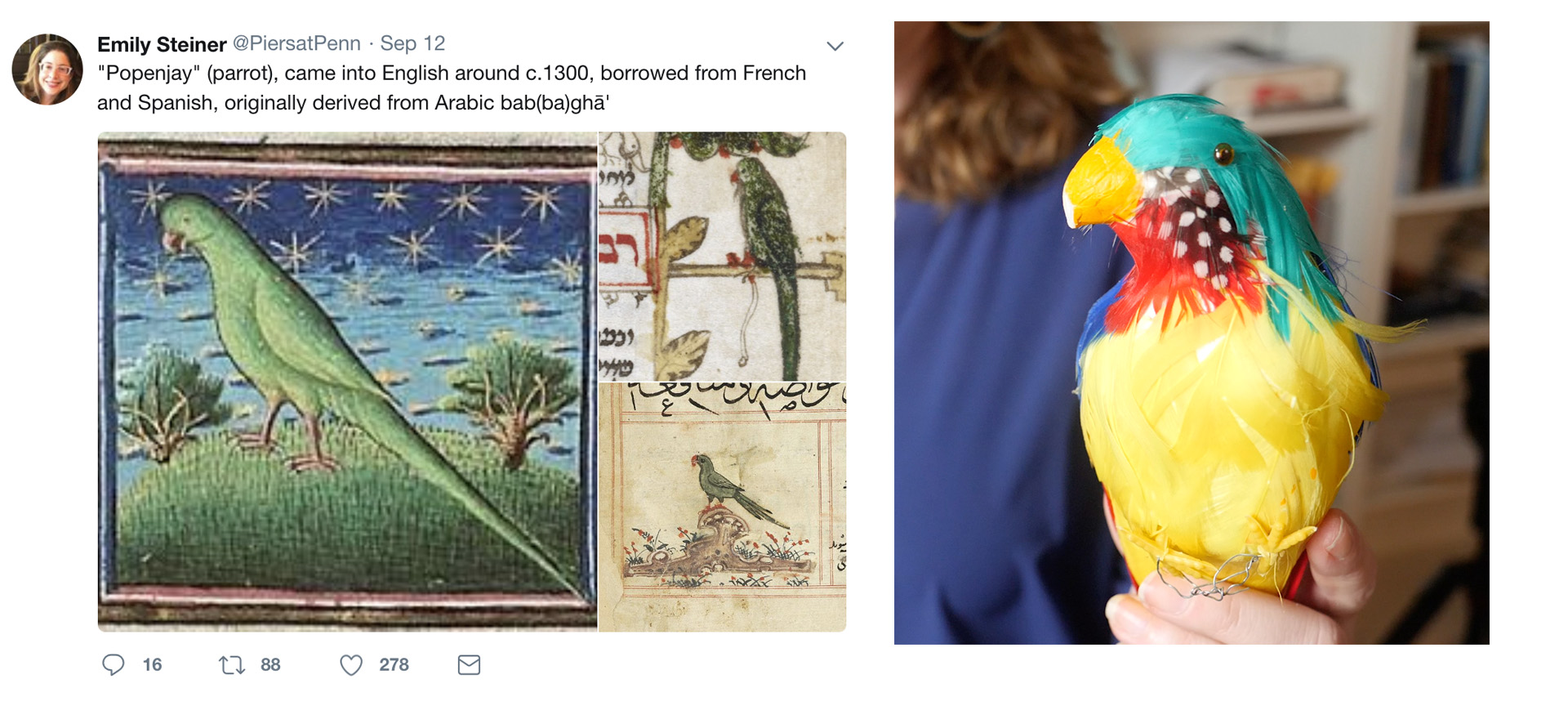

“I was determined to use this word popenjay,” Steiner says, which is what brought a stuffed parrot out of her basement and to the scene as a prop. Used frequently until about 150 years ago, the word can mean parrot, but is often used in Middle English to describe someone who is proud and conceited, a trait assigned to their candidate Pernel Puddingheart. It comes from the Arabic word for parrot, babagha, via Spanish. “I felt like it had this rich linguistic history.”

The words that didn’t make the cut? “Wanhope was one of our favorites,” Malcolm says. It’s the same word as despair but in the sense of a darkening of hope. “We weren’t sure how we were going to show that,” Steiner says.

Many favorite words had to be sacrificed to get it under the minute limit, since their first draft ran three times that length. Steiner’s experience on Twitter was helpful there, too. “That short-form discipline of Twitter, I think, is a potentially creative form. It's the same with a 60-second lecture,” she says.

Ultimately, the performance was the priority, not playing the part of the illustrious expert.

“I said to myself, ‘You know what? I'm going to throw dignity out the window,’" Steiner says, “because otherwise how am I going to get people to hear what I have to say about medieval words?”

. . .

Click here to watch Professor Emily Steiner and Aylin Malcolm's entire 60-Second Lecture, Lost Words: 5 Medieval Words That We Need Right Now.