Students of the Occult

In a class this semester, Becky Friedman, C’10, Associate Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of English, leads students down the dark, historical spiral of witchcraft, examining its persecutorial past and transition to palatable and raucous entertainment.

Three mottled crones stirring a frothing cauldron—it’s a near-unanimous mental evocation when the word “witch” dare be uttered. But the trope made famous by Shakespeare, says Becky Friedman, C’10, only scratches the surface of something ancient and storied that cuts across time and geography and is mired in violence, and, eventually, comes to epitomize how society molds taboo subjects into entertainment.

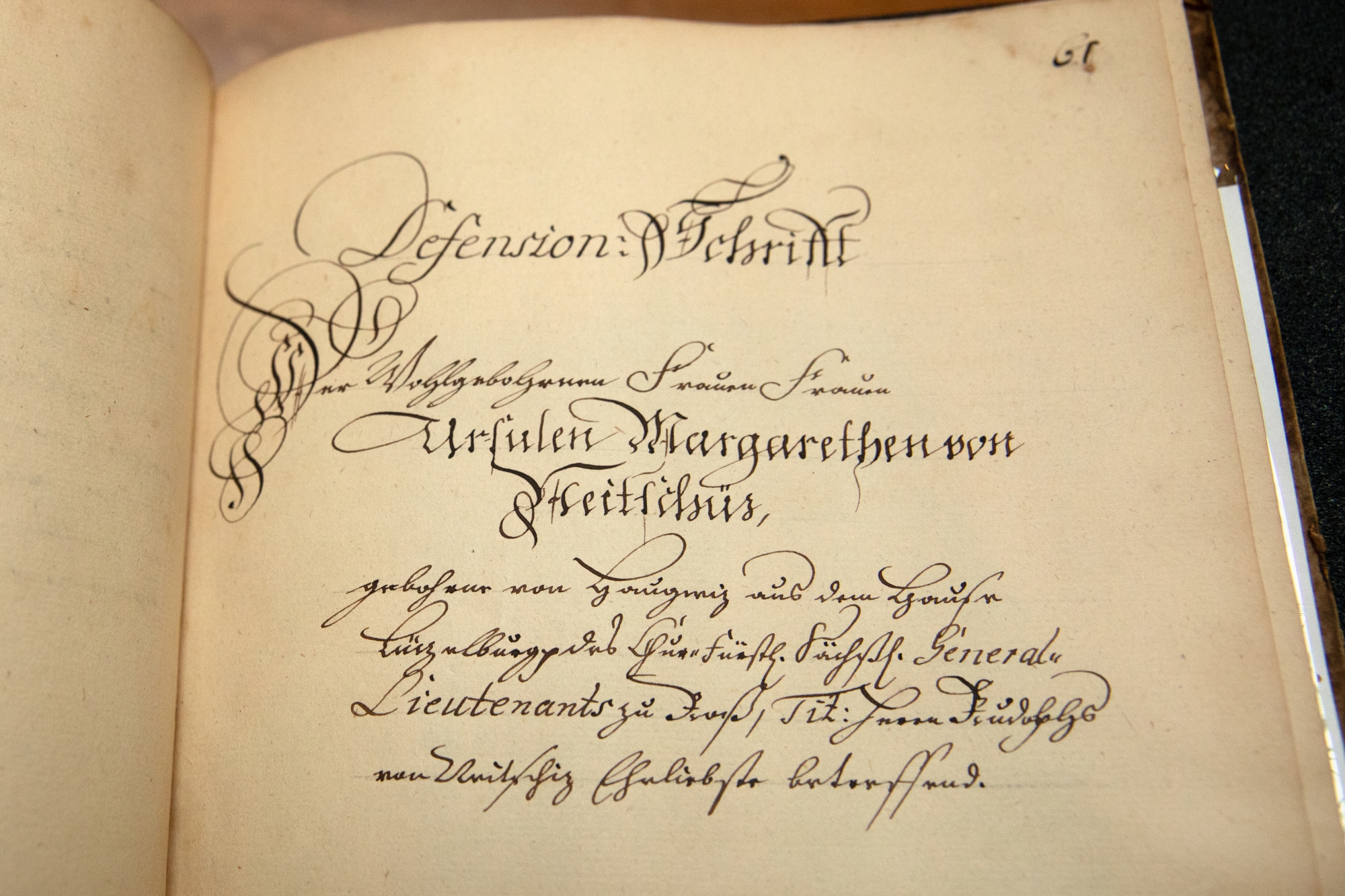

The lore behind the witch archetype is inextricably tied to the development and distribution of the printed word and is enmeshed in all manner of fraught topics, according to Friedman, Associate Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of English. In her class, Witchcraft and the Occult, students examine said texts, mostly of European origin, that document firsthand historical accounts of witchcraft and demonic possession, giving them an eerie, intimate window into how accusations of occult practices resulted in all-too-real legal proceedings and executions.

“Extra! Extra! Read All About It!”

Often, these accounts were recorded in pamphlets, which were short, unbound, easy-to-distribute books. “Pamphlet literature was affordable and could address a range of readerly interests, including social, political, and religious issues, but also more sensational matters like witchcraft cases,” says Friedman, whose own research focuses on religion during the English Renaissance and the ways in which deviations from contemporary ideas of “Englishness” resulted in exclusionary attitudes.

“Some of these printed materials cover witch trials—allegations, the interrogator’s questions, and the accused’s answers,” Friedman continues. “So, there’s a sense that these documents can give us a front-row seat to the judicial proceedings of the time.”

In addition to pamphlet literature, students also delve into seminal works that addressed the occult, including Reginald Scott’s Discovery of Witchcraft, published in 1584, which approaches witchcraft with serious skepticism, and the Malleus Maleficarum, which translates to “Hammer of Witches,” published by two Dominican friars in 1486 in Germany. The latter text played a large part in mapping the persecutory process of witches at the time, tying witchcraft to heresy, which would ultimately result in the execution of those found guilty.

Danju Zoe Liu, C’26, mentions a 1646 collection of confessions and testimonies from eight witch trials. “These confessions had absurd and humorous moments—for instance, the Devil is a cat named Tissy in one—but they also serve as reminders of the humanity of both the accused and the accusers, posing difficult questions about the psychology of fear, blame, and belief.”

This type of persecution in Europe became widespread in the 15th century and lasted for hundreds of years. Some accounts put its victims in the hundreds of thousands, most of whom were female. Even female healers, unable to get accreditation for practicing medicine, might be accused simply for providing care.

“There were many categories of witchcraft, which could include sorcery, necromancy, and demonic pacts, but then there was also a more benign form of magic performed by ‘cunning folk,’” says Friedman. “In England, people would go to these practitioners for charms, cures, balms, all kinds of treatments and help, but it was sort of a fine line between being able to heal the sick and having inexplicable access to powers.”

Devilish Depictions and Artifacts of Power

Students spend a large portion of the class analyzing depictions of witchcraft across other various mediums, examining the transition of witchcraft from object of persecution to taboo-shattering entertainment. It wasn’t without its diabolical rumors and controversy, however.

“Playwrights adapted witchcraft narratives, capitalizing on the spectacle of occult rituals and the drama surrounding the people who performed them,” says Friedman. “Over time, rumors would sometimes emerge that actual devils would appear on the stage. That says something about the danger or scandal associated with witches, even in theatrical settings.”

One assignment involves students reflecting on the ways that news reports and pamphlets from the period interacted with popular entertainment culture of the time. “They’re tracing the connections between historical documents and the plays that draw from them, considering why a playwright might turn to recent events for source material and how these productions entertained while they explored questions of religion, authority, morality, and much more,” says Friedman.

Another assignment sees students choosing a film that includes a representation of either a deal with the devil or witchcraft and analyzing how depictions have either remained consistent or evolved.

“There’s a media blitz around the movie Wicked now, for instance, and that film engages with many of the ideas we’re examining in class, such as difference, exclusion, power, and, of course, witches,” says Friedman. “These representations should be familiar to us because of the ways they’ve been reproduced on the stage and on the screen in the centuries since they were first constructed. As in Shakespeare’s time, popular culture continues to produce content that reveals our fascination with the occult and the figures who engage with it.”

To give students an in-person glimpse of some of these macabre texts, Friedman helmed a class trip to Penn’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts. There, they studied a selection of materials linked to the occult in various forms, all deriving from issues connected to the historical period. This included a few artifacts, like a dagger used in old productions of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and associated with Edwin Booth, a famous actor in his day and brother of John Wilkes Booth, the infamous assassin of Abraham Lincoln.

“The dagger prop led me to learn that Edwin and John Wilkes had a sibling rivalry sparked by their father, which reflected violence both on stage and in real life,” says Alexander O’Connor, C’25, who adds that he’s been “enchanted”—pun intended—by the discussions that have arisen in class. “Only by continuing into the rest of the semester will I learn what more witchcraft has in store,” he adds.

And how does a class centered on the occult celebrate Halloween?

“Every day is Halloween in this class,” Friedman laughs. “But we are going on an excursion to the University Club for lunch. So, I guess you could call it our own little Witches’ Sabbath for All Hallows Eve.”

Liu says the semester has, so far, been “magical, one of the most memorable classes I've taken at Penn,” she says. “Through the lens of witchcraft, this class has fostered fascinating discussions about the line between news and entertainment, religion and power, and fears surrounding the female body.”