As a graduate student in Penn’s English PhD program, Lauren Alcindor had visited plenty of archives, yet she had only a vague sense of what an archivist actually did.

“In my mind,” she says, the work “took place alone in a small, dark room.”

Now she knows that notion is less than accurate—a fresh insight she arrived at by way of a graduate-level internship course, Professional Archiving and Curating for Academic Settings, offered for the first time in the fall 2024 semester. Co-taught by Zita Nunes, Associate Professor of English, and Holly Mengel, Head of Archives and Manuscripts Processing at Penn Libraries, the course gave students firsthand experience processing an archival collection and sharing their work through a pop-up exhibit.

“Even for students who don’t want to be archivists,” says Mengel, “understanding what happens to a collection before it reaches them can make them a better researcher.”

Getting the Big Picture

The idea for the course came about, explains Nunes, when she was graduate chair of the English department and saw how students’ career goals were changing. While some PhD students still aimed for tenure track positions, others sought alternate avenues. The course she developed with Mengel equips students with skills in archival processing and introduces them to professional archiving as a possible career path.

The first few classes focused on the big picture of archiving. How are collections acquired? What does it mean to process one? What ethical issues can arise? How are materials preserved? The curriculum then progressed to covering the history of specific archives, including those in Penn’s Kislak Center, around which the course was centered.

By week four, boxes had been brought out of storage and gloves donned for the hands-on portion of the course. Those boxes—more than 20 in all—contained the Kislak’s recently acquired Karen Burke LeFevre Research Collection, as-yet unprocessed and ready for the students.

The materials in this collection tell several stories.

One relates to Frances Steloff. Born to Russian-Jewish parents in 1886, Steloff was the founder of New York’s famed Gotham Book Mart, which became a haven for avant-garde writers including Saul Bellow, Marianne Moore, and Arthur Miller. A second story is about Karen LeFevre, an English professor who, in the 1990s, set out to write a book about Steloff and the Gotham Book Mart. A third thread tells of the censorship the bookstore—a focal point for controversy over banned books—experienced and the copyright dispute that ultimately led to the cancelation of LeFevre’s publishing contract. Mengel says she chose this collection because she thought its literary nature would mesh well with the students’ interests and because it had “so many little nuggets and human moments.”

Up Close and Processing

The group spent much of the semester organizing the collection and consolidating the boxes, whittling them down to a more manageable 16 and categorizing the materials by broad themes useful to researchers.

One of the least understood aspects of archiving, says Mengel, is that no piece of paper is important on its own. “As an archivist works through a collection, they don’t make a decision about a single piece of paper,” she says. “They make a decision about how those pieces of paper work together. A lot of preliminary thought goes into how the papers reflect what a person did or what their work process was—Karen, for example, was influenced by meeting Frances Steloff and that changed the way she worked—and only then can the archivist begin to understand the collection and sort through the materials.”

Nunes, whose research focuses on African American and African Diaspora literatures, says both she and her students were struck by seeing how many decisions individual archivists make and how these practices impact the final form of a processed collection. “Realizing that there are many ways to engage with the material,” Nunes says, “and that the way it’s presented is a snapshot in time tied to a set of decisions will help us when we’re researching in archives in the future.”

On a practical level, the students physically removed paper clips, sticky notes, and staples—all bad for paper—and placed items in acid-free folders and boxes. They identified material to be digitized and earmarked fragile papers for conservation. Mengel was surprised by how much the students relished these more tangible aspects of the course.

“I thought they would enjoy the theoretical thinking more than the tedious, repetitive work,” she says, “but they were happiest when they had things in their hands and were working on actual collection material. That really seemed to make a huge difference in their overall understanding.”

The final step in organizing the collection involved creating a finding aid, an online document that includes a short description of the materials, biographies of the key players, and an inventory detailing everything in the collection.

“We had to be careful because PhD students in the humanities like to write a lot,” says first-year English PhD student Jordan Trice. “We had to remember our own research experiences when we would often glance over the finding aid without reading the entire thing.”

Telling Their Story

Because teaching from a collection is an important part of academic archival work, the students created blog posts about the collection and others in the Kislak Center, as well as created a pop-up exhibit for the final class assignment. Alicia Meyer, a Kislak Center curator, helped them think through how best to present the collection to an audience encountering it for the first time.

“It was an interesting experience because there were eight students in the course, and we had all seen different parts of the collection, so we all had different areas where we wanted to turn our attention,” says Trice. “We had to work together and see how we could tell a full story.”

Meyer helped them “see the forest for the trees” by disconnecting them from the “nitty gritty stuff” they had been embedded in while processing the collection and leading them in a crowdsourcing exercise to identify major themes that could be illustrated with concrete examples.

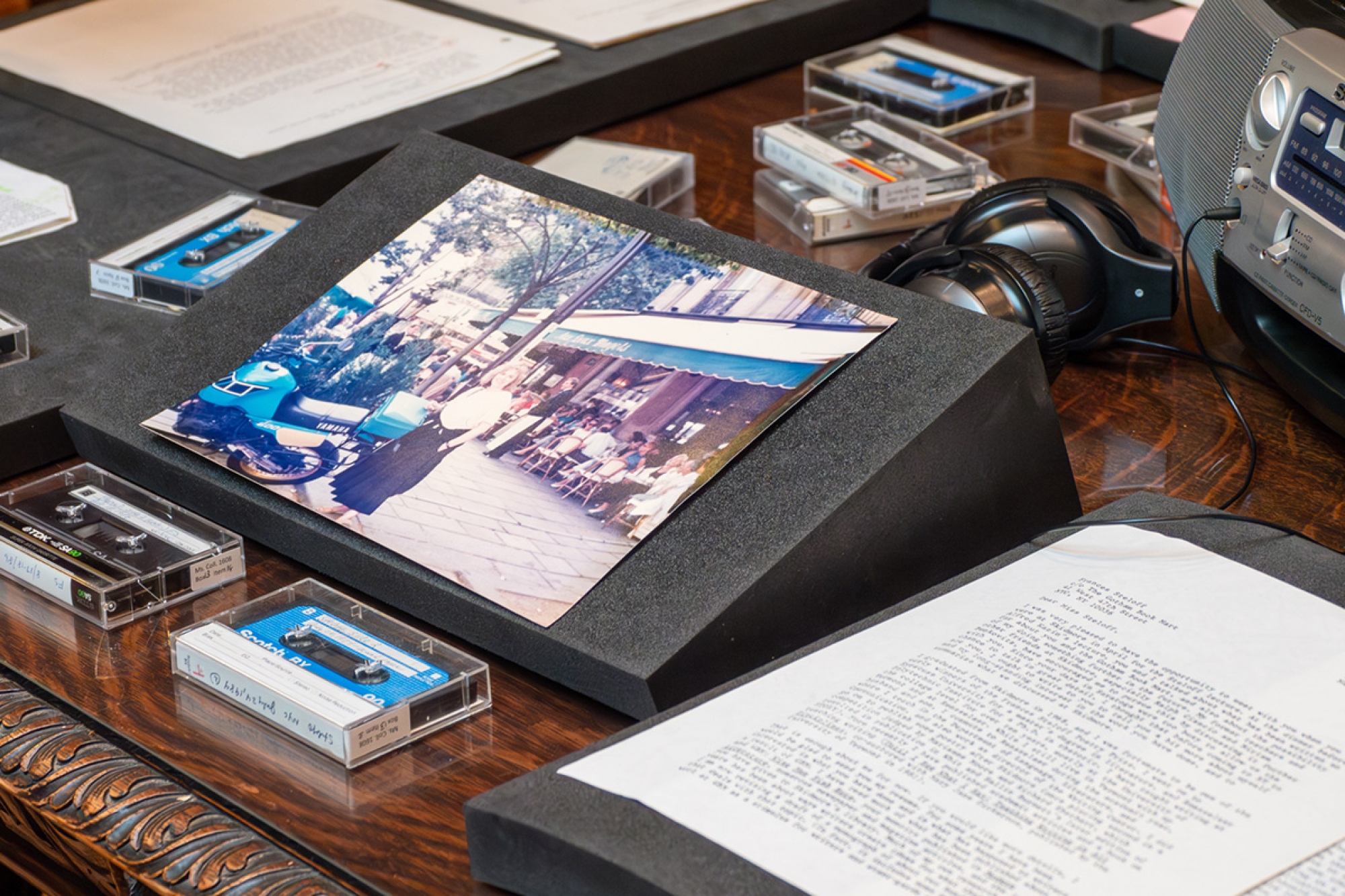

The exhibit, which took place in the Lea Library on December 5, featured a large round table with objects that told the story of Steloff and the Gotham Book Mart, a table in the back filled with banned books that had been seized by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (a public morality watchdog disbanded in 1950), and a third table that recreated LeFevre’s desk—with work papers and cassettes and headphones strewn about—showcasing her experience as a scholar trying to tell Steloff’s story before hitting legal roadblocks.

I thought they would enjoy the theoretical thinking more than the tedious, repetitive work, but they were happiest when they had things in their hands and were working on actual collection material. That really seemed to make a huge difference in their overall understanding.

“That was the narrative the students wanted to tell,” says Meyer, “how Gotham had experienced this period of censorship and how Karen herself had her own experience of censorship. It was useful to them as researchers early in their careers to situate their own moment in history and look back at how another scholar, like Karen, or somebody in the literary world, like Frances, had managed those issues.”

Alcindor admits she had some anxiety about how the audience would connect with their framing of the collection, especially since LeFevre herself attended virtually (with the help of an owl camera). “I wanted to make sure I did Karen’s story justice,” Alcindor says, “and I was nervous to recount part of her story in front of her, but I think it worked out.”

Meyer says the exhibit was “a tremendous success” because the students “managed to both get their own voices in there and make room for the audience to interact with the objects, to think about questions of censorship and academic integrity and all of the intellectual issues that the collection brought up for them.”

Inspired by the Kislak Center curators and archivists she met, Alcindor says the course “definitely showed me possible options I might want to pursue after my PhD.” She also gained “a really deep understanding of how archives work and the dynamics of the people who maintain them.”