Omnia 101: Listening to Music

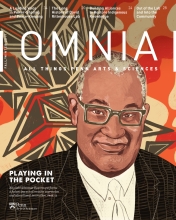

Jairo Moreno, Associate Professor of Music, explains how listening is at once historical, social, personal, affective, and technical.

Omnia 101 offers readers a peek into what faculty do every day in their classrooms, and how they bring their expertise to the next generation.

Did you ever hear a song that was popular when you were younger, one you hadn’t heard in years? Maybe you were surprised by how quickly and effortlessly the lyrics come rushing back. Jairo Moreno, Associate Professor of Music, says that such a modern, personal relationship with music can be traced, roughly, back to Beethoven, whose compositions and approach to the circulation of music caused a radical shift in the way music was experienced, even if audiences at the time couldn’t explain it. “We don’t necessarily have to know that the crooner is possible because microphone techniques were developed that allowed for that sort of whispery intimate voice to be recorded,” he says. “We just hear that somebody’s speaking to us.”

In this installation of Omnia 101, Moreno, a Grammy-nominated bassist, considers what we mean when we say we listen to music, and how that meaning changes depending on time, place, and cultural expectations. The author of a major study of the history of listening in early modern and modern music and a professor of introductory and advanced music theory, his musical appreciation runs the gamut from Mozart (“incredibly complex”) to Dolly Parton (“a musician’s musician”) and Missy Elliot (“ahead of her time”).

What is the difference between hearing and listening?

Hearing describes the sense of perceiving sound, whilst listening entails some sort of intention. Even if you’re not “paying attention,” with listening there is a possibility you will be called upon by the sound. In recent decades, there has been lot of theorizing that says that listening is always a relationship between things. There is sound—and sometimes that sound is music—but then there is something else that listens. Only analytically, and not practically, can we pull them apart.

Are there standard listening practices?

Different cultures and expectations have developed around listening. The contemporary concert hall, for instance, inherits from the 19th century certain attitudes about what it is to listen. Among other things, those attitudes require silence from the listeners. It involves a particular form of submission, willful and productive, but none the less, a submission.

Then there is the more contemporary example of a DJ performing for a massive group of dancers. Is the DJ “playing?” Are the dancers “listening?” In a way, yeah. The dancers are listening in that they are attuned to something, and the listening becomes dispersed through bodily activity. Though they are part of a group, each dancer experiences the sound through individual consciousness and embodied experience. And dancers and listeners enter in a feedback loop with the DJ, who in a way, listens back and calibrates her tracks in response. Listening straddles the collective-individual assemblage even as it can encourage sharp distinctions within it or blur them altogether.

How has technology shaped how we listen?

Beethoven was a composer who obsessed over trying to fix every aspect of musical notation. Obsessed, and failed, in a way. He spent much of his life adding words on top of the music, trying to tell the performers how to play here, how to play there, doing the best he could within the constraints of his notation system. Then we entered the phonographic era, and instead of notes written on a page, music could be circulated aurally.

Let’s imagine I am a ten-year-old using music editing software like Garage Band or Logic: I could create and combine sounds, and learn how to deal with them, really early on in life. That sort of making, that composing, that putting together—it was not possible when you inscribed music via notation. These are not radical shifts in themselves, rather they represent recalibrations of the interfaces by which music is registered. Listening, though it too changes, remains a constant.

Can you teach people to be “good” listeners?

I have children, so I know, anecdotally at least, that young people listen a lot, and they’re very judgmental about what they like and what they hate. Sometimes it’s just a simple reaction: “Oh that’s the music of my parents,” or, “Dad, this is weird.”

One thing you can do is try to have them articulate what they like or don’t like about a song. Often, that’s rhythm or beat. We have a species-given capacity to attune to cyclic repetitions of some kind—it’s just part of who we are.

If you start there, you can move to things that may be less obvious. Is a song repetitive? Does it have a melody? We have genres of music for which melody is not valued and others for which it is central. A good pop tune—it could be the Jonas Brothers, Ariana Grande, or Ed Sheeran—will tend to have a melodic line. In rap, you can focus on the delivery of words in a complex and creative way, very different than what a pop song is trying to do.

There’s a lot of comparative work that can be done by listeners. Why and how does Billie Eilish sound different than Miley Cyrus? That’s a debate between my daughters. They can see, in different modes of musical organization, something significant, and relevant to their interests as listeners.

Does musical knowledge make for a better listening experience?

There is an argument that goes something like, “Well, you’re robbing the mystery of the music, because now I understand the powers by which it moves me!” But the reality is that when you press play, music’s powers do not wane by the fact that you can now name the chorus and the verse. With knowledge, I hope there is a sense of discovery, an excited, “Oh! Listen to that part!”

What music do you like listening to?

I love jazz, and jazz as a modern aesthetic phenomenon values complexity and virtuosity, while there are other types of music for which that is not important. But as a music theorist, I’m always listening to different kinds of music. I’m amazed by the many ways in which we, as a musical species, are able to shape sound. It never ceases to amaze me that there’s always something, anywhere in the world, anywhere in time, that is just so marvelously creative and impactful.