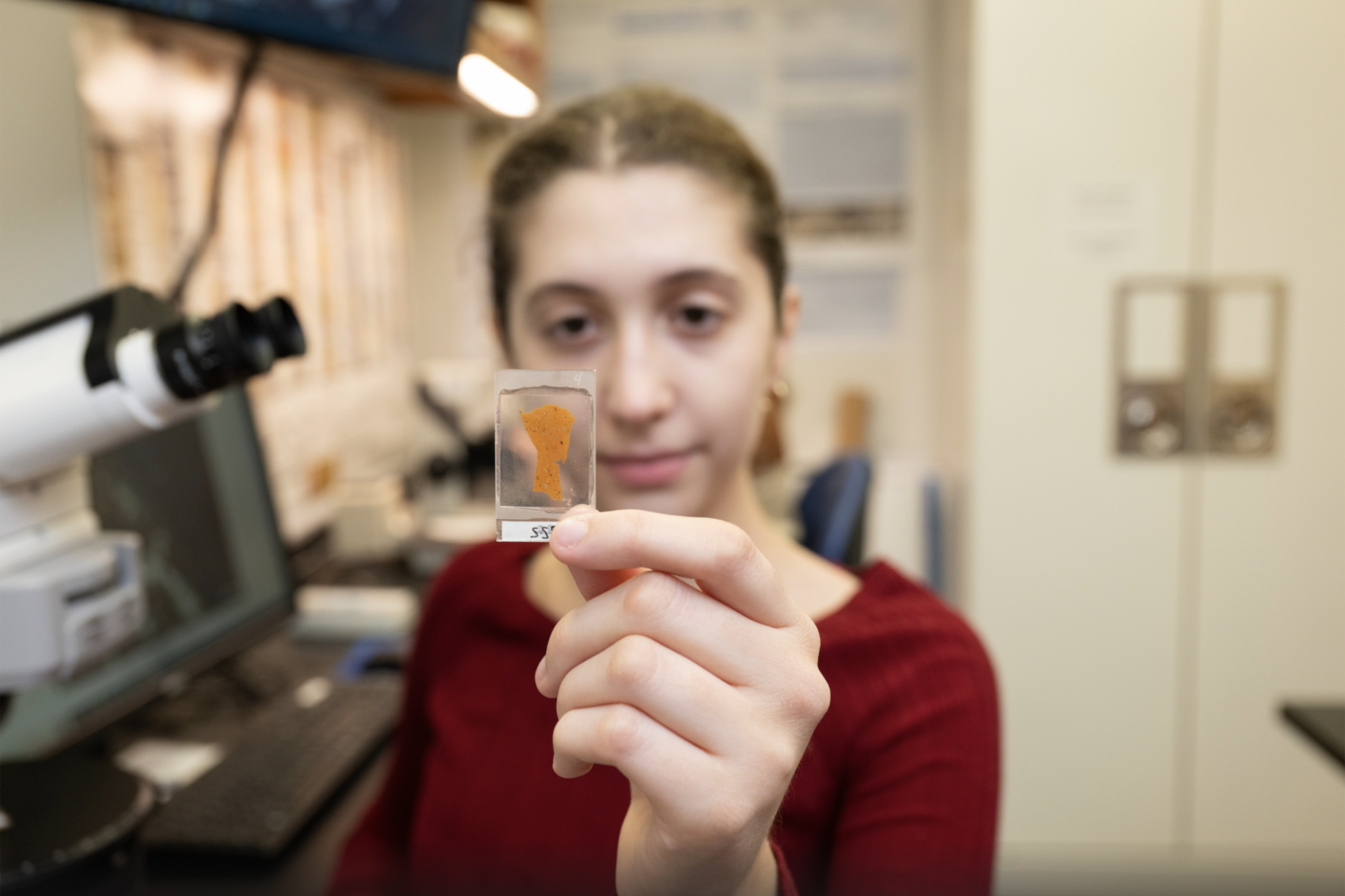

Doctoral candidate Mark Van Horn has been tracing the economic networks of the ancient Roman Empire through its cooking pots. As it turns out, family farmers among a network of rural sites in southern Tuscany made very few of their own ceramics, as had been the longstanding assumption, but rather imported them from producers who made them 50 or more miles away. Van Horn determined this through a scientific technique known as ceramic petrography, a skill he honed working with mentors in the Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials (CAAM).

“CAAM has been completely integral to my entire dissertation and graduate experience,” says Van Horn, who will soon defend his PhD dissertation.

This year marks the 10th anniversary of the opening of CAAM, a joint endeavor between Penn Arts & Sciences and the Penn Museum. Some 2,600 students have come through the center, which teaches and mentors undergraduate and graduate students in a range of scientific techniques crucial to archaeologists and other scholars. It provides laboratory and classroom facilities, materials, equipment, and expert personnel as students seek to interpret the past in an interdisciplinary context that links the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities.

We’ve really spent the past decade ensuring we are at the forefront of teaching archaeological science.

It all began when Marie-Claude Boileau, CAAM Director and Teaching Specialist for Ceramics, and Tom Tartaron, Associate Professor of Classical Studies and CAAM Executive Director, assembled a laboratory to understand the production, usage, and cultural significance of ancient ceramics. It was a proof of concept that was so successful, according to Tartaron, that it inspired an ad hoc committee to discuss furthering archaeological education at Penn.

“We were originally interested in putting together a series of archaeological labs, but that led to the idea of forming a partnership between SAS and the Penn Museum, and equally important, to launching a whole associated curriculum,” Tartaron says. “We wanted the center to be about teaching and mentoring, not just about research, and with donor support, we were able to make CAAM a reality in 2014.”

Boileau notes they were thoughtful in developing CAAM coursework. They wanted classes taught by specialists who could present archaeological science in an applied and hands-on way to any Penn student, from first-year undergrads through advanced PhD students. Today, the program covers metal, ceramic, and stone analysis; botanical and zoological remains; and conservation. “We’re uniquely positioned at the Penn Museum with access to its incredible collections,” Boileau says. “We’ve really spent the past decade ensuring we are at the forefront of teaching archaeological science.”

Students from across the University can take CAAM courses like Food and Fire: Archaeology in the Laboratory, which uses artifacts to understand how the archaeological record can trace breakthroughs such as baking bread, weaving cloth, and firing pottery and metals. In another, Introduction to Digital Archaeology, students are exposed to the field’s broad spectrum of digital approaches; the class emphasizes fieldwork through a survey of current literature and applied learning opportunities that focus on the study of areas associated with African American burial practices and cemeteries in Greater Philadelphia.

Since 2014, more than 20 courses have been created or adapted for CAAM’s curriculum. Though CAAM is not a degree-granting program, it does offer a minor in archaeological science, a graduate certificate in archaeological science, and the opportunity for independent studies. CAAM also has fellowships and graduate assistantships in collaboration with the Penn Museum.

Van Horn, who has taken the majority of the courses CAAM offers, says that instruction significantly broadened his understanding of different kinds of archaeological study methods. Another doctoral candidate, Christopher LaMack, has also taken numerous CAAM courses in support of an archaeology-focused degree from the Department of Anthropology. He is also a teaching assistant in CAAM’s Digital Lab, and has been a research assistant on various CAAM lab projects.

“CAAM is an incredible resource for students in terms of training, equipment, and expertise,” LaMack says. “It’s also a source of intellectual and social community within the Museum—anchored by world-class researchers—that brings together students and others from diverse departments and scholarly traditions. CAAM elevates the study of the past at Penn beyond what’s available at peer institutions.”

Significantly, Van Horn adds, CAAM offers undergraduates a unique opportunity to experience and learn about archaeology firsthand. “Something that really sets CAAM apart is the degree to which undergraduate opportunities exist within the space,” he says. “Learning alongside graduate students helps undergraduates reach for the next level of content, in my opinion, but it’s also a chance for them to enroll in classes that often have original research as the product rather than a paper or final exam. It’s a really good way for students to, in some cases, get a publication before they finish their undergraduate degree—to be able to do that as an undergraduate is huge.”

Even with the growth that’s happened the past 10 years, Boileau and Tartaron are looking ahead. They recently completed a three-year growth plan for CAAM that aims to expand the types of courses offered, as well as provide more lab and fieldwork opportunities locally and abroad.

It’s a far cry from where it all began, Tartaron says. “We had to convince people that this thing would work: ‘If we build it, will they come?’ And the answer has been resoundingly yes,” he says. “Students who take our courses are coming from all over the University—different programs, different majors. It’s been extraordinarily successful, and that’s why our 10-year celebration is a true celebration of growth and potential for the future.”