Lessons in Philosophy

As philosophers-in-residence at the Academy at Palumbo in South Philadelphia, Ph.D. students Jacqueline Wallis and Afton Greco are teaching high schoolers how to contemplate life’s big questions.

Afton Greco stands in front of 23 ninth graders in a world history class at the Academy at Palumbo in South Philadelphia, her backdrop a slideshow with passages from Leviathan by 17th-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Greco, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Philosophy, is sharing strategies for reading philosophical texts amid the students’ unit on the Enlightenment.

“Philosophers have a lot of really interesting things to say, but a lot of them are bad writers,” Greco begins.

She instructs the high schoolers not to worry if they don’t understand everything on the first read, priming them with several questions to consider as they parse the text. Reading aloud, Greco pauses at bolded words to ensure students know what Hobbes meant by “nature” and “confederacy” and “industry,” and students share their thoughts on Hobbes’s conclusions about the need for authority to avert war. During the next period, Greco repeats the lesson, which ends with a spirited discussion among a few students about the meaning of a sovereign.

Greco is one of two “philosophers-in-residence” at Palumbo, along with fellow fourth-year philosophy doctoral candidate Jacqueline Wallis, who taught the same lesson to two classes earlier in the day. Embedded in the school for about 10 hours a week, one of their roles is to provide what they call a “push-in,” which involves dropping into any 9th- through 12th-grade class, by request of the teacher, to discuss philosophical issues around a topic related to the course material. They also run a Philosophy Club that meets weekly after school, help teachers come up with discussion questions for lessons, and provide other professional development.

The mission of the program is really to bring opportunities to engage in philosophy and philosophical thinking to students who don’t really have a chance to do that.

“They’re good at getting the students to think about difficult questions in a way I think is manageable,” says J.P. Leary, the Palumbo instructor who teaches the world history class and who previously brought in Greco and Wallis to talk about freedom. His goal, he adds, is to encourage his students to be curious and open-minded.

“Comfortable in Our Uncertainty”

Wallis began as a philosopher-in-residence in January 2023 with Yosef Washington, GR’23, then a philosophy Ph.D. student at Penn. Greco joined last fall. As their first push-in, Washington and Wallis taught a lesson about theories of time travel for a class reading Octavia Butler’s time travel novel Kindred.

This past fall, Wallis also provided a lesson on philosophical theories of time for an astronomy class. “It’s not a settled question what time is, so I think it was fun for the students—in a science class—to get exposed to questions that weren’t settled,” she says. She has also offered push-ins on evaluating evidence in environmental science and the ethics of stem cell technologies.

Wallis says teachers have told her a few times that more students participate in these discussions than normal. Greco thinks one reason is that “these students see Jacqui and me being comfortable in our uncertainty, which is maybe a newer thing for the students. So many of these questions are open-ended. There’s a range of answers that seem reasonable, but we don’t really know which one is right.”

Beyond Standalone Programs

The philosopher-in-residence program is an initiative of the Philosophy Learning and Teaching Organization (PLATO), a national group dedicated to bringing philosophy and ethics into schools. The program at Palumbo is administered by Penn’s Project for Philosophy for the Young (P4Y), which philosophy professor Karen Detlefsen—now vice provost for education—founded in 2014.

“One of the most exciting aspects of P4Y is the role that graduate students play in producing ideas for innovative programming and in putting these ideas into play,” Detlefsen says. “The ideas that Afton and Jacqueline have developed through their engagement with the philosopher-in-residence program are perfect examples of this.”

Dustin Webster, a postdoctoral fellow serving as P4Y co-director adds, “The mission of the program is really to bring opportunities to engage in philosophy and philosophical thinking to students who don’t really have a chance to do that.” He notes that though philosophy is common enrichment in private schools, he believes it’s an opportunity all students should get.

Penn P4Y originally began working with Palumbo as part of an Academically Based Community Service course, through Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships, focused on an event called the National High School Ethics Bowl. Detlefsen and Webster brought a regional Ethics Bowl competition to Philadelphia in 2020. The event differs from a debate in that students are not assigned opposing views but rather have open-minded conversation about difficult subjects.

Until last year, P4Y largely provided standalone programming, such as running an after-school club. But these activities were not always integrated into the school, Webster says, and, while there are options for curriculum development for educators, he adds, “teachers are already so overworked and overburdened it’s hard to want to add things to their plate.”

That’s what made PLATO’s philosopher-in-residence program so appealing to P4Y. PLATO launched the program in a Seattle elementary school in 2013, and it has since grown. Thanks to a grant from the Whiting Foundation, PLATO funded the pilot expansion in January 2023 into three high schools across the country, including Palumbo. The others are in Seattle and Boston. PLATO Executive Director Jana Mohr Lone says she reached out to Penn because she knew the school’s past work with philosophy for young people, and Webster is on PLATO’s Academic Advisory Board.

“Wondering about the world is a really important part of being a human being, and young people wonder about all kinds of things,” Lone says. “At some point I think many of them get the message that that’s not really a valuable way to spend your time. Engaging in philosophy reminds them that you can wonder about these questions your entire life.”

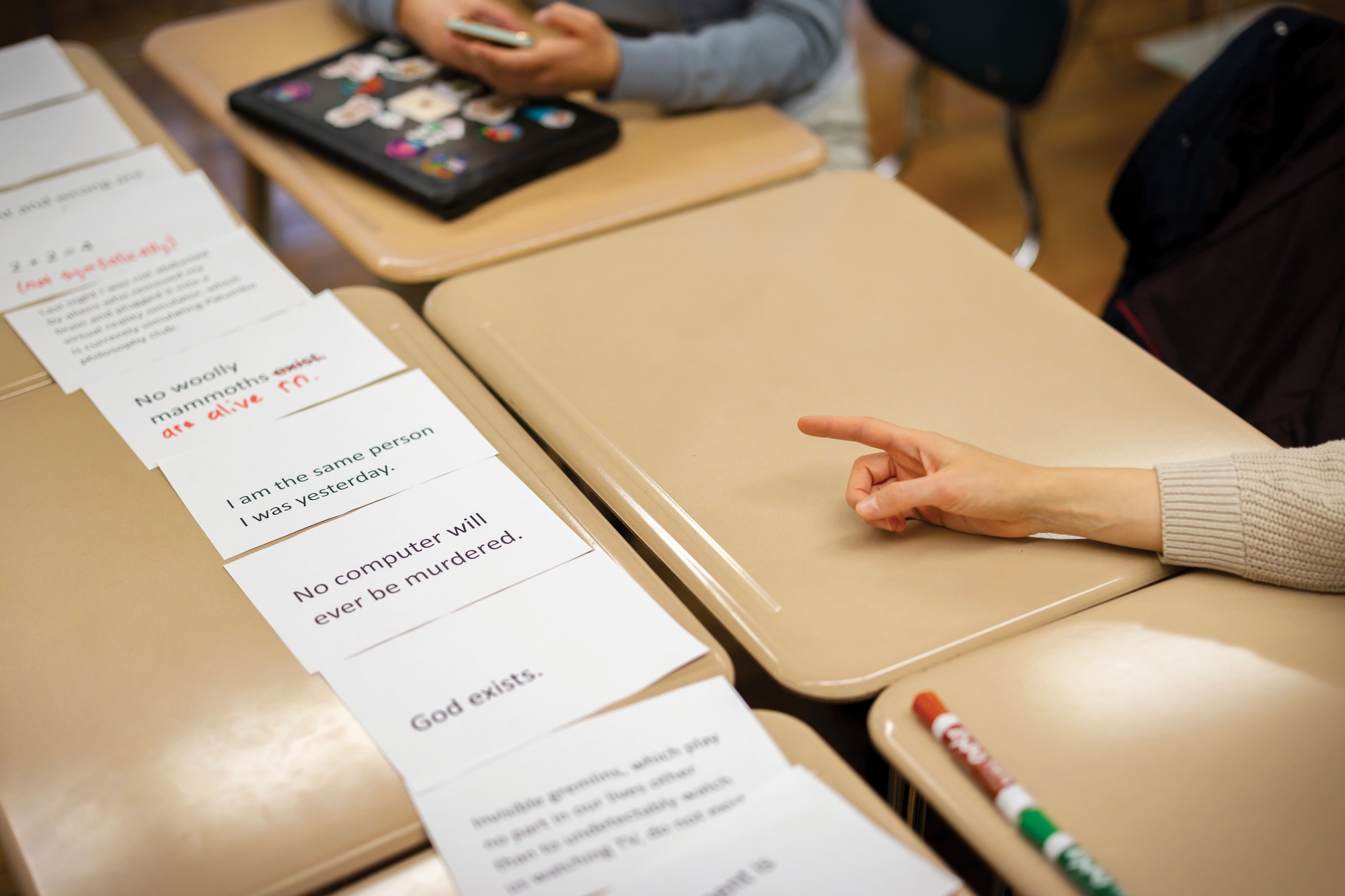

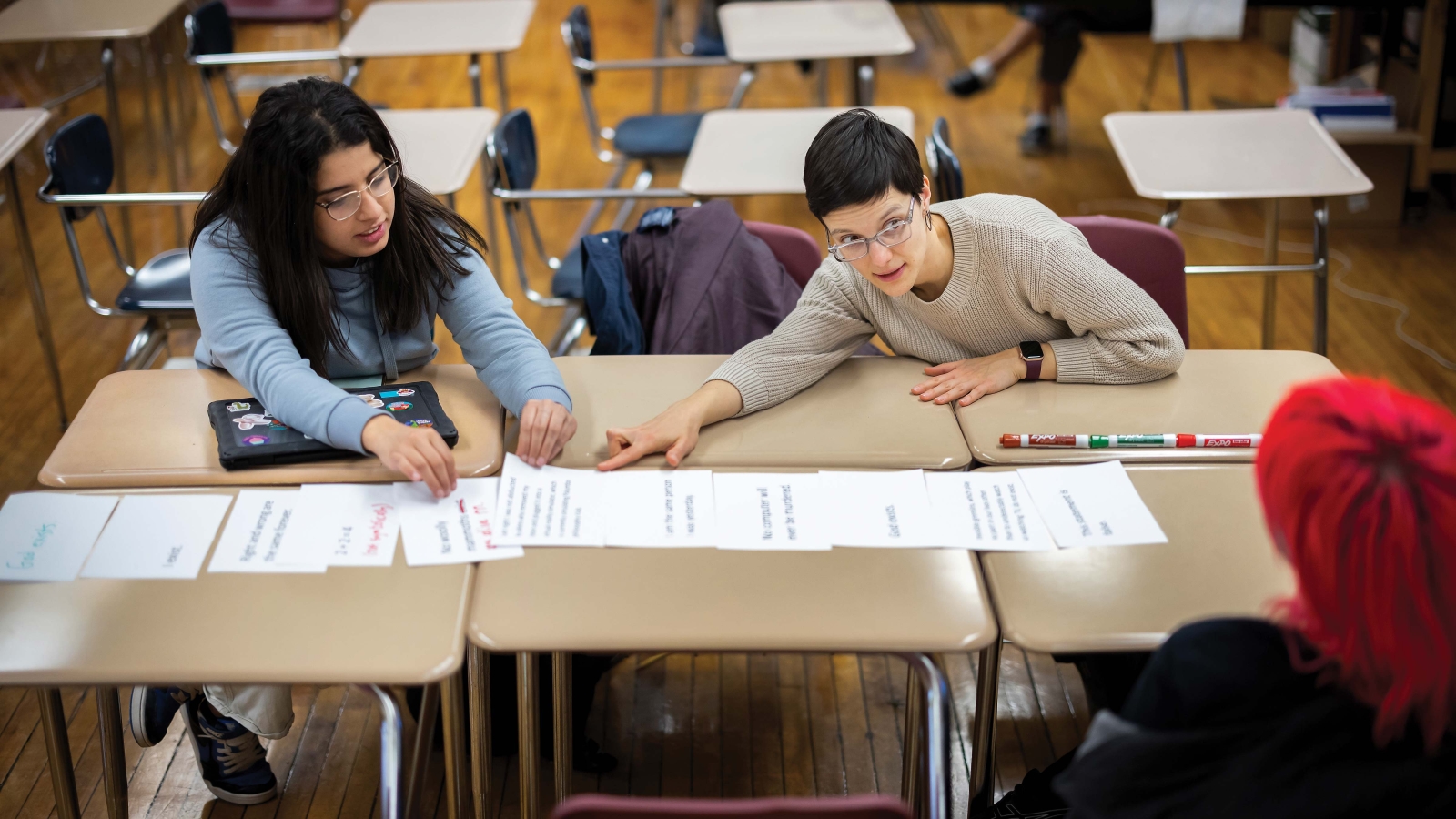

Here Wallis talks with students during an after school philosophy club she runs with Greco.

Extracurricular Thinking

As part of the philosopher-in-residence program, Wallis and Greco run an after-school Philosophy Club, an informal gathering where students can show up as little or often as they like to discuss a range of topics. At the students’ request, the focus of the fall semester was bioethics, Wallis says.

One Thursday, after the two conclude their four push-ins about how to read philosophical texts and the school day ends, they and a few high school juniors, including Marty Signes, Oreoluwa Oyefeso, and Adina Cooper, convene to talk about Jean-Jacques Rosseau—a good bookend to their conversations about Hobbes earlier in the day.

“I really like to talk to people who think about things,” says Signes, who would like to eventually major in philosophy in college. She recalls trying to talk to someone about the trolley problem—the ethical question of whether to sacrifice one person in order to save a group of people—and getting the reaction, “That’s so dumb because it’s never going to happen to me.” But Signes says she wants to talk about much more than only what might affect her.

So many of these questions are open-ended. There’s a range of answers that seem reasonable, but we don’t really know which one is right.

Oyefeso tries to encourage people to think beyond themselves, too, to contemplate how what they do might affect others and the planet. “People are not really open-minded when it comes to talking about philosophy,” Oyefeso says. Nor are they always willing to change their minds, Cooper adds. “I like saying, ‘How do you know that?’”

The club is an outlet the high school students indicate they don’t always get elsewhere. Like with the philosopher-in-residence program as a whole, they are guided by Greco and Wallis, given a space to contemplate big questions surrounded by others doing the same.