Letters from a Titanic Survivor

Sophie Michi, a master’s student studying English, transcribed correspondence from the noted maritime disaster while learning to work with archival material.

Sophie Michi’s not big into romance, or comedy either. She gravitates toward “whodunits, action movies, thrillers. I love the movies where the world is ending,” she says.

This might explain why Michi, a master’s student in the English department, transcribed handwritten letters from Titanic survivors as part of a project for the course Professional Archiving and Curating for Academic Settings, co-taught by Holly Mengel, Head of Archives and Manuscripts Processing at Penn Libraries, and Zita Christina Nunes, Associate Professor of English.

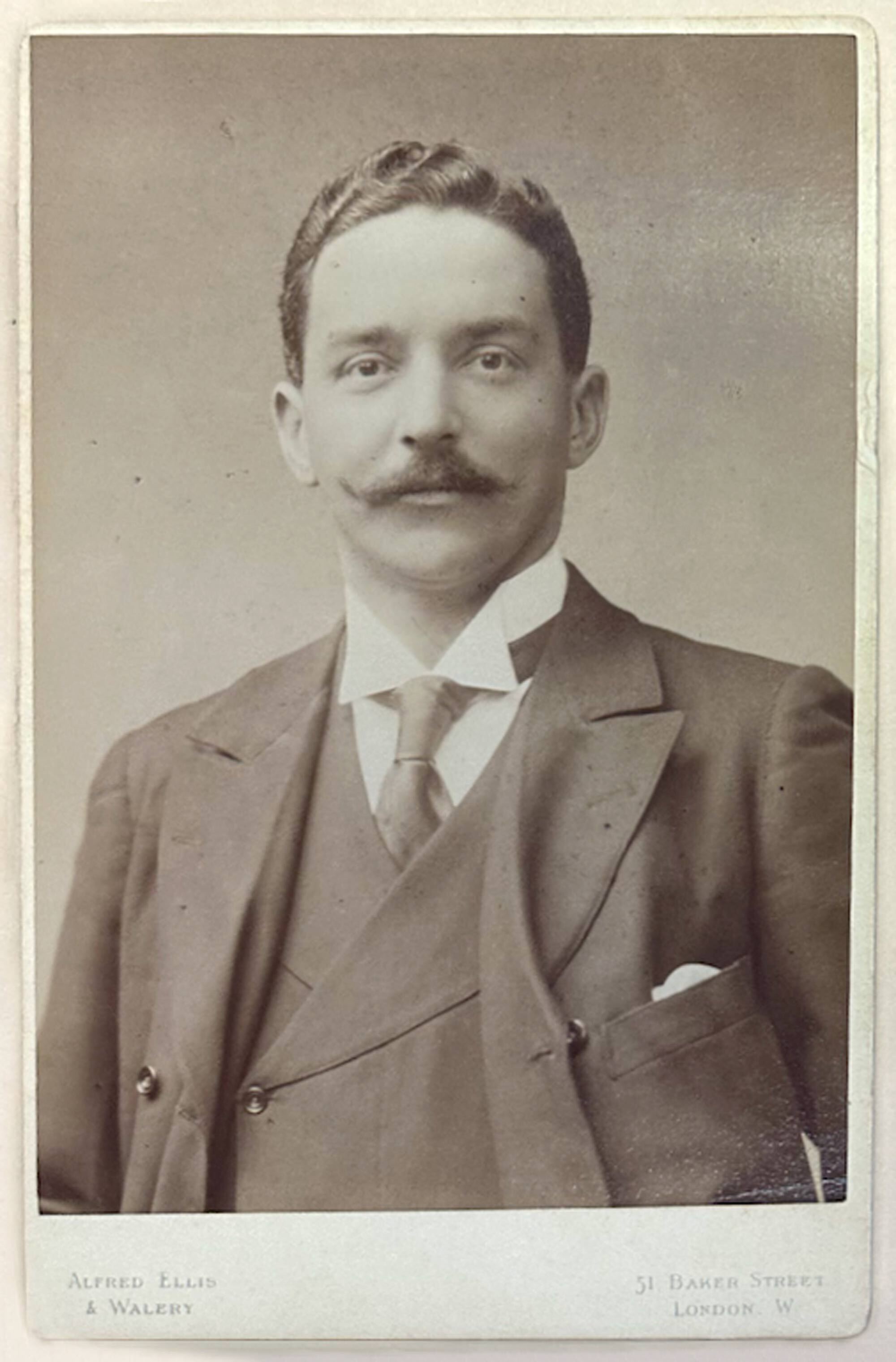

Joseph Bruce Ismay, Chairman of the White Star Line and President of J.P. Morgan’s International Mercantile Marine Company, was a passenger on the Titanic who survived the fateful April 1912 accident. (Image: Thayer Family Material/Penn Libraries, photographed by Sophie Michi)

Mengel and Nunes hosted guest speakers every week, Michi says, including one who presented on paleography—the study of handwritten materials. Mengel pulled up samples from the Penn Libraries, one of which was a letter from the “John B. Thayer Memorial Collection of the Sinking of the Titanic,” housed at the Kislak Center for Special Collections.

Michi was riveted.

It was like the point in an archaeological movie when the protagonist uncovers some lost thing, she says. Reading the letters was “like decoding something, like a spy. It was a little bit of a thrill.” The sinking of the Titanic is such a well-known incident, she adds. “You grow up knowing about it. It’s always on your radar.”

The project wasn’t without its challenges. The early 20th-century cursive, for example, proved harder to transcribe than Michi had originally assumed it would be. “At first, I saw them, and was like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t read anything.’” Together with Mengel, Michi carefully combed through one page, front and back; slowly, with context, the letter came together. “When you get a new skill,” Michi says, “it’s like a door that unlocks.”

After that initial success, Michi transcribed several more letters on her own. They revealed the deep remorse of Joseph Bruce Ismay through letters written to Marian Longstreth Thayer, the widow of Ismay’s friend and business partner, John B. Thayer, who died after the Titanic struck an iceberg and sunk into the Atlantic Ocean in April of 1912.

Ismay, of course, survived. Two first-class female passengers, whose own husbands had died, suspected that because Ismay was chairman of the White Star Line, he had received preferential treatment at the expense of women and children. Ismay, who writes that he was ordered to board a lifeboat along with another gentleman when there were no more women and children in sight, felt he should have “gone down with the ship,” Michi says. He was only exonerated after a painful trial, details of which the archive also included, in the form of newspaper clippings.

Throughout the trial, Ismay corresponded with his friend’s widow:

I cannot interest myself in anything, my mind seems to refuse to retain anything but the recollection of that awful disaster. I can only hope that time away helps me. What an ending to my life. Perhaps I was too proud of the ships & this is my punishment, if so it is a heavy one.

The letters show the burden that Ismay carried, Michi says. “The man is so apologetic. He’s distraught. He’s been put in the line of fire for this.”

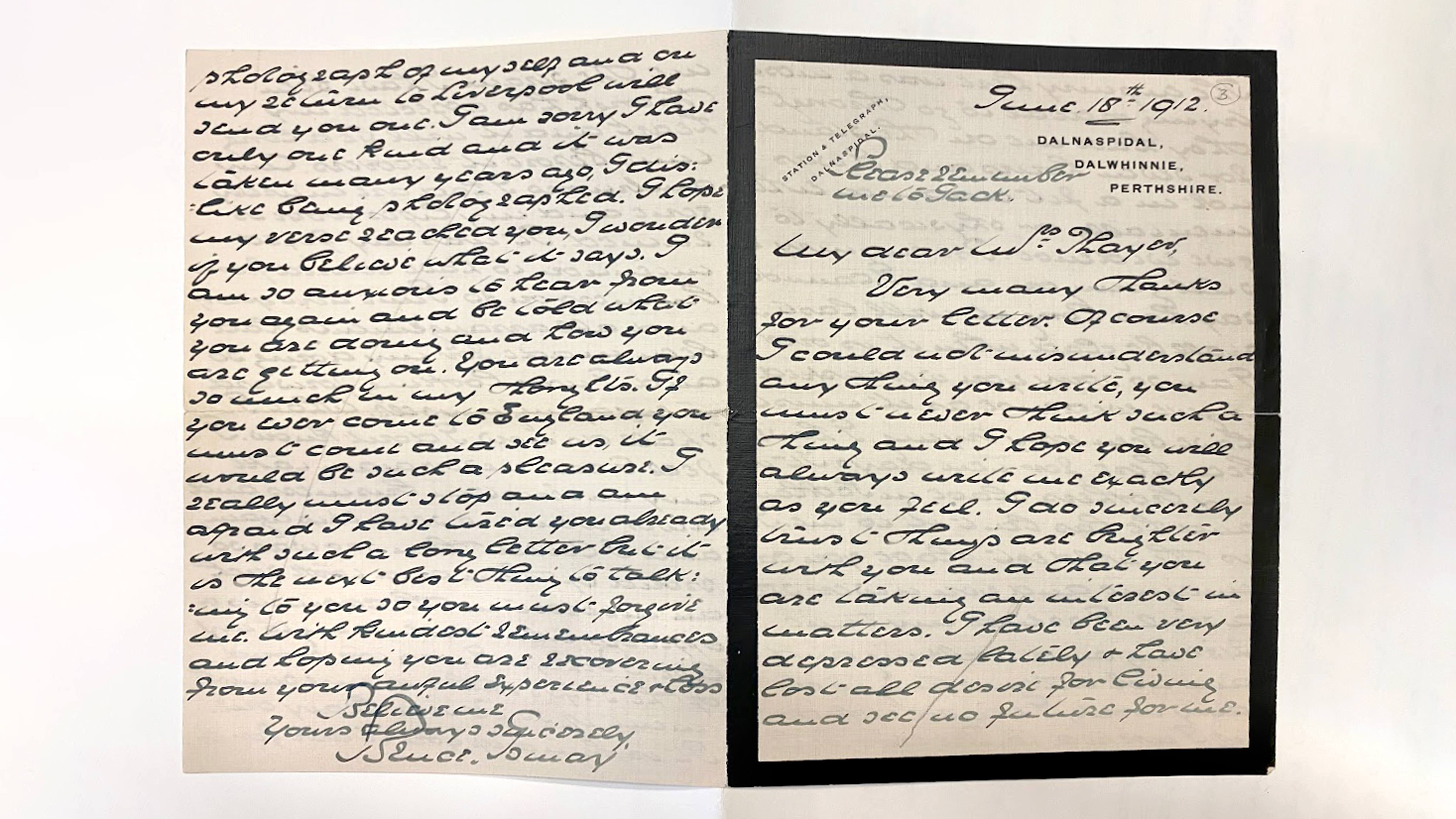

A letter from Ismay to Marian Longstreth Thayer, the widow of Ismay’s friend and business partner, John B. Thayer, who died on the Titanic. (Image: Thayer Family Material/Penn Libraries, photographed by Holly Mengel)

While Ismay suffered from survivor’s guilt, both he and Thayer also seemed to be plagued by depression. “I do hope you are bearing under your awful sorrow,” Ismay wrote to Thayer. “I am sure you are acting bravely and not giving way and thinking of others who are so dependent on you and who you love. I cannot tell you how sorry I was to hear your trouble has returned and that you are suffering and sincerely trust it may soon pass away.”

Michi, who is Indian and Italian, says she is drawn to heroic acts in history. She comes from a family of Italian restauranteurs, and according to family lore, her grandmother hid Jewish people upstairs while feeding Mussolini’s generals downstairs at her restaurant. “These were regular people,” she says, speaking of her family. “Lots of people did something to help.”

The same was true around the Titanic sinking, a disaster that forever impacted countless lives of ordinary people. The letters between Ismay and Thayer, Michi says, came from a time in history that she will never know, an archive that showed the disaster’s long tail. “How many people,” she says, “get the chance to have something real from that tragedy, or the aftermath of that tragedy, right in front of them?”