Give and Take

Assistant Professor of History of Art Shira Brisman explores how printmakers of the Northern Renaissance promoted the open exchange of artistic ideas.

In the 15th through 17th centuries, artists sought inspiration not only by copying nature, but also by making careful selections from one another’s work. Assistant Professor of History of Art Shira Brisman explores how artists of the period used pictorial and textual language to represent the free exchange of creative ideas.

Trained as a print scholar, Brisman examines the interplay between German printmakers and metalworkers in a recent paper, “A Matter of Choice: Printed Design Proposals and the Nature of Selection, 1470 – 1610,” published in Renaissance Quarterly. It won the 2019 Schulman and Bullard Article Prize from the Association of Print Scholars, which recognizes publications featuring innovative research on prints or printmaking by early-career scholars.

“In the middle of the 16th century, artists who were trained in metalwork also began to publish designs in the form of prints,” Brisman explains. “We call them goldsmith-engravers.” These artists produced booklets that offered wildly inventive proposals for metalwork objects with title pages plainly stating that the designs were available for use by fellow craftsmen.

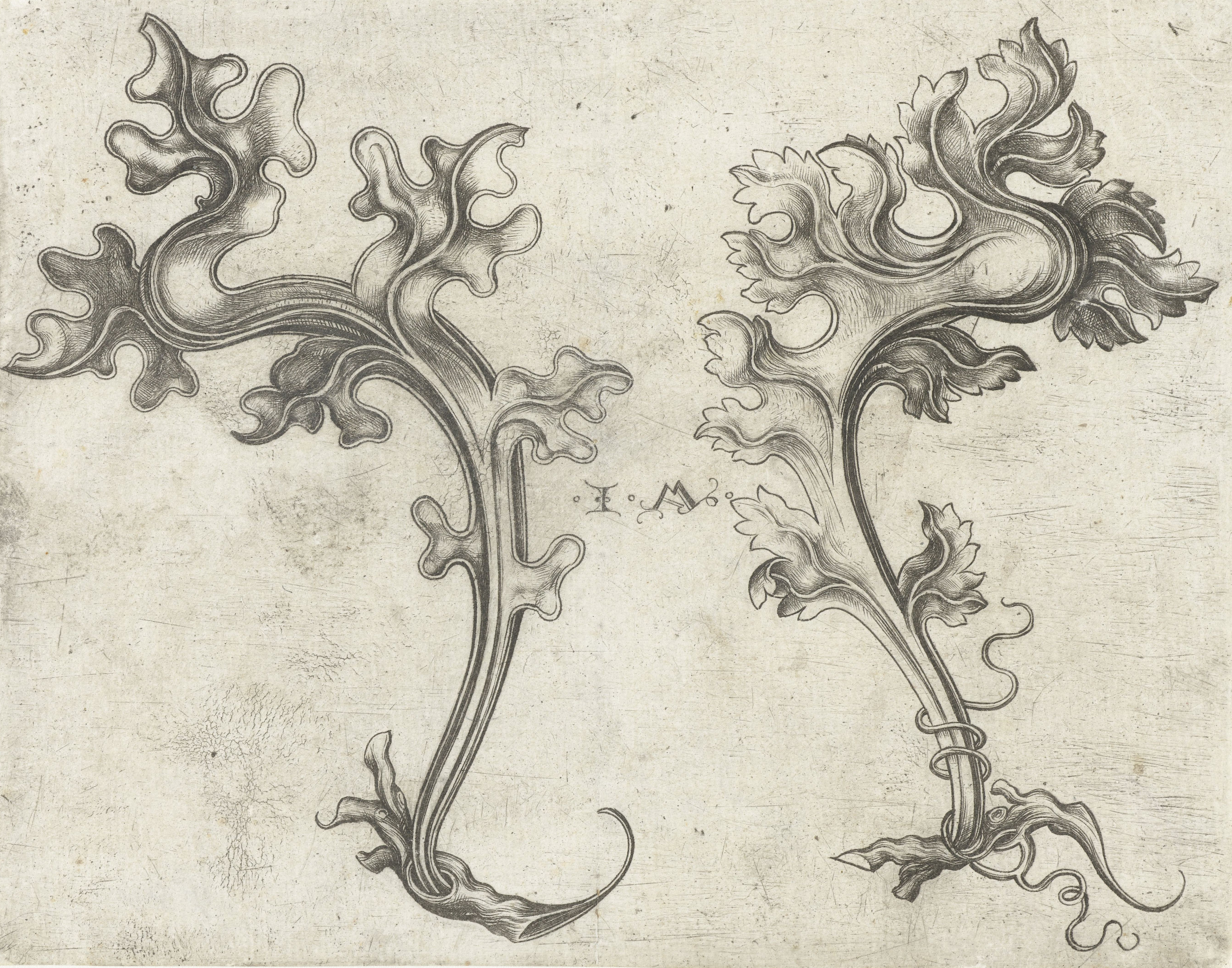

“These booklets, with their explicit addresses to other artisans, seemed to me to be formalizing indications of this communication that are detectable earlier—that is to say, before they start to verbalize with written words the invitation ‘make of my ideas what you wish,’ they were finding ways to promote this message visually,” says Brisman. “And one of the ways in which they do this is through motifs of ornamental foliage—stems, vines, and growths that pour forth from the earth. The sharing of designs becomes pictorialized through motifs of picking, plucking, and cutting. They make visible a metaphor, operative in textual sources at the time, that art gets its ideas from nature.” In her paper, Brisman argues that these artists were in fact behaving like nature—offering the fruits of their labor for others to take.

To Brisman, these communications represent a theoretical language about usage and ownership—what we now think of as intellectual property. “My research is motivated by questions that shape our culture today—to whom does an image belong, and how widely can it be shared?” she says. “The careful and rewarding process of working historically means that I apply these questions back to the period I’m invested in and say, ‘Well, what terms need to change? How do we understand the differences between their society and ours? How can we train ourselves to pick up on their hopes, their fears, and their jokes?’”

Her research also revealed that these gestures of sharing were only one side of the coin. City records from the period indicate that artists sometimes sued each other in disputes over materials, tools, and motifs.

To be sure, artists and artisans of the Renaissance had reason to be protective of their output, since they competed for commissions. And the Protestant Reformation in Germany in the 16th century meant there were few commissions coming from the church, the major source of patronage for metalsmiths.

“Martin Luther was very concerned about the corruption of people paying for their salvation through the commissioning of these valuable objects,” says Brisman. “Another concern was that there was simply too much gold stuff, too many shiny things. The Church was distracting people from devotion by having so many reliquaries dedicated to different saints.”

Restrictions placed on what churches could display led them to try to redistribute precious metal objects by melting down and repurposing the metal, or moving the vessels to the domestic realm. “I think it’s important to see the redistribution of crafted objects and waning of commissions as a backdrop to what the artists are doing,” she says. “They are showing how generative their ideas are, how many things they can make. They’re trying to advertise their creativity as having applications beyond the church. But there is also an urgency to keep artistic creativity alive. Though the behind-the-scenes court cases show them very much concerned about who owns and has rights to what sorts of tools, molds, and motifs, the rhetoric they produce is one that encourages taking, using, and adapting pictorial ideas into new forms.”

Brisman thinks these artists were participating in the creation of community in the sense that they were addressing audiences of fellow craftsmen. In some instances, they used imagery to make fun of one another’s names or to trade private jokes and insults. “To do research on prints is like eavesdropping on a conversation,” she says. “Prints often nest intimate messages within their seemingly public address. ‘Reading’ these prints alongside commissioned metalwork can provide commentary on these formal pieces of craft. Looking at a gilded-silver centerpiece is like watching an operatic performance. Looking at prints is like sneaking in backstage.”

The printed booklets—and the earlier, one-off engravings that look ahead to them—also address the non-artist who appreciates art for its own sake.

“Prior to the sixteenth century, drawings mostly stayed in workshops and were passed down from an artist to his protégé,” Brisman says. “This is something that changes in the early modern period with the advent of collecting prints—the notion that somebody who is not him or herself an artist could take interest in a work on paper that presents itself as being provisional, a medium in which we can see the artist’s mind at work.”

The concept of creativity as something that springs from the mind of a solitary artist persists today, but Brisman sees the creative act differently.

“I see creativity as residing in the act of making your ideas available for other people,” she says. “That is what the idea of the generative nature of art is in this period, and that’s different from the notion that artistic genius comes from a place of isolation.”