A Classic Hat Trick

In one year, Sheila Murnaghan, Alfred Reginald Allen Memorial Professor of Greek, published a translation of Medea and books on the Beat generation and classics for children.

“I have a problem saying no to things,” says Sheila Murnaghan on how she managed to publish three books in 2018. “I’m really interested in what makes classical literature speak to people today and finding the less obvious or counter-cultural strands within antiquity.”

In a four-month span Murnaghan, the Alfred Reginald Allen Memorial Professor of Greek, published a new Norton translation of Euripides’ Medea; the essay collection Hip Sublime: Beat Writers and the Classical Tradition, co-edited by fellow Penn classicist Ralph Rosen, Vartan Gregorian Professor in the Humanities; and Childhood and the Classics, coauthored with Deborah H. Roberts, a professor of classics at Haverford College.

The three projects required different mindsets. “For Medea, my only collaborator was Euripides,” says Murnaghan, whose approach to translation treads a line between “the literal and the spirit…. You can’t be too experimental in a work intended to present students with a surrogate for the Greek text,” she says. “We’re living in an era of many wonderful adaptions of classical works, where creative writers are rewriting tragedy so that it resonates with contemporary issues, but if you want people to be able to appreciate what an adapter does, you have to give them something that represents the original.”

The collection Hip Sublime looks at how the ancient classics influenced the work of the Beat generation, including Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, but also less-well-known authors like Kenneth Rexroth and Diane di Prima. Flourishing in the wake of World War II, Beat writers distanced themselves from the common culture of the time and are seen as non-traditional, but the book examines all the ways they were shaped by and responded to the classics.

“One of the things that reworking the classics does is bring different facets of the material to light, so that you see that a poet like Catullus—whom many people read in an intermediate Latin class because his Latin is relatively accessible—was actually a very avant-garde writer,” Murnaghan says. “To the Beats, that made him seem like a soulmate. Sappho, the only female Classical poet who survives to us in any large amount—it’s easy to see her as a counter-cultural figure. They were out there, ancient poets who could seem subversive.”

Murnaghan brings that approach to the classroom in courses like The Odyssey and Its Afterlife. “I want to disrupt the idea that ancient texts are monolithic and upholding a single set of very often hierarchical values. In fact these works are really questioning the values of their society in all kinds of ways.”

Beat writers also saw themselves in the big mythic narratives of the classics, she says, especially in the epic hero’s descent to the underworld, and were interested in mythic patterns that transcended the divide between East and West.

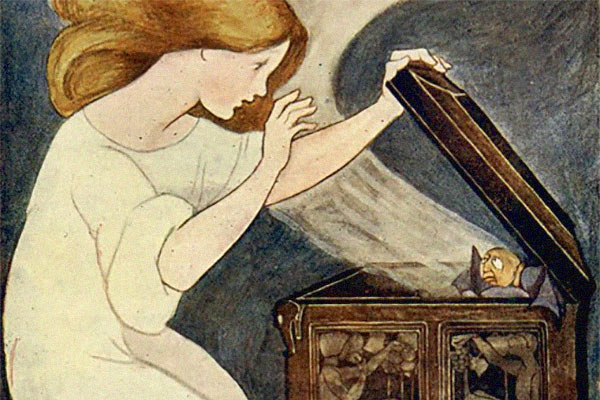

The book Childhood and the Classics, on how classics were transformed into children’s literature, spans the mid-19th century to about 1965. Children were taught the classics before then, says Murnaghan, but often with dry, academic handbooks. Then in the middle of the 19th century there was an explosion of children’s literature intended to be read for pleasure rather than education.

One of the people most responsible for this change was Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter. “Most people today think of him as the author of this book they had to struggle through in high school, but he actually wrote fantastically engaging and interesting versions of classical myths for children,” Murnaghan says. “His first book was called A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys—he put girls first, which is really interesting.”

Murnaghan believes Hawthorne and his British counterpart, Charles Kingsley, had multiple motives for their work: stimulating imagination, enlarging sensibility, and introducing moral empathy—not to mention making money. “Through the years people have also felt it was important for children to know classical mythology and ancient history for cultural literacy, and so the inviting, child-friendly versions are a way of drawing them into this knowledge,” she says.

The authors end the book in the mid-1960s, following the publication of the D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths in 1962 and on the brink of new developments that included a “jokier and, in some ways, less confident approach,” says Murnaghan. “It was like, oh, here are these hoary classics, but we’ll jazz them up by making fun of them and retelling them in new genres.”

Writers and entertainers today continue to find new ways to introduce the classics to young people. Murnaghan cites the bestselling Percy Jackson series by Rick Riordan, in which the main character’s father is the Greek god Poseidon. Other forms include comic books, video games, and fan fiction.

“The ancient myths are widely known in a way that transcends the individual moment and becomes available to everyone,” she says. “This is where I think being given classical mythology in childhood really plays a role, because you are given a version of these myths that you can inject yourself into.”

Beyond that, she hopes people will turn—or return—to the classics throughout their lives. “I think it’s a real shame if these great works of classical literature are only read by 18- to 21-year-olds. They have a lot to say to people at all stages of life.”