Black Voices on Confederate Monumentation

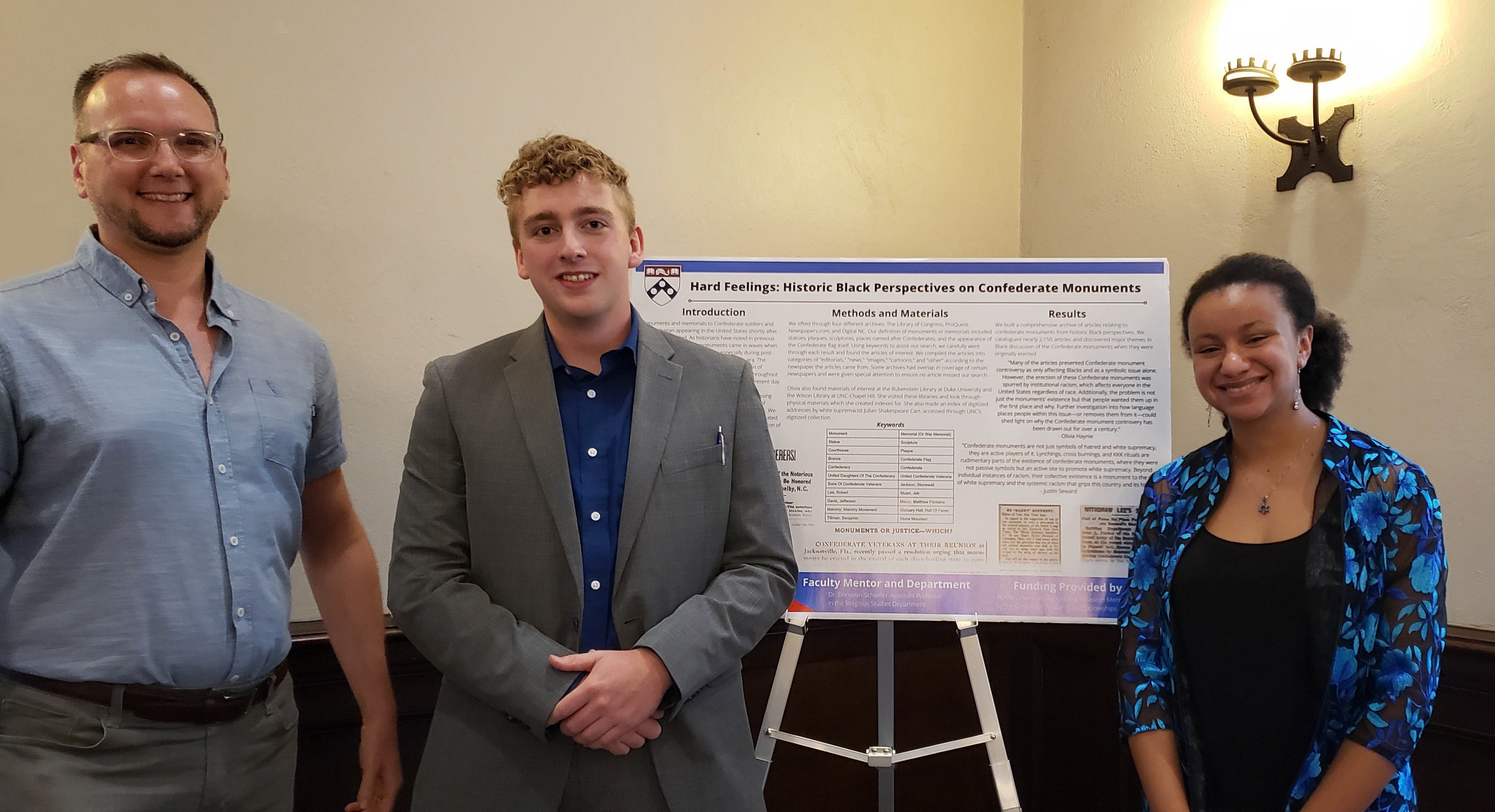

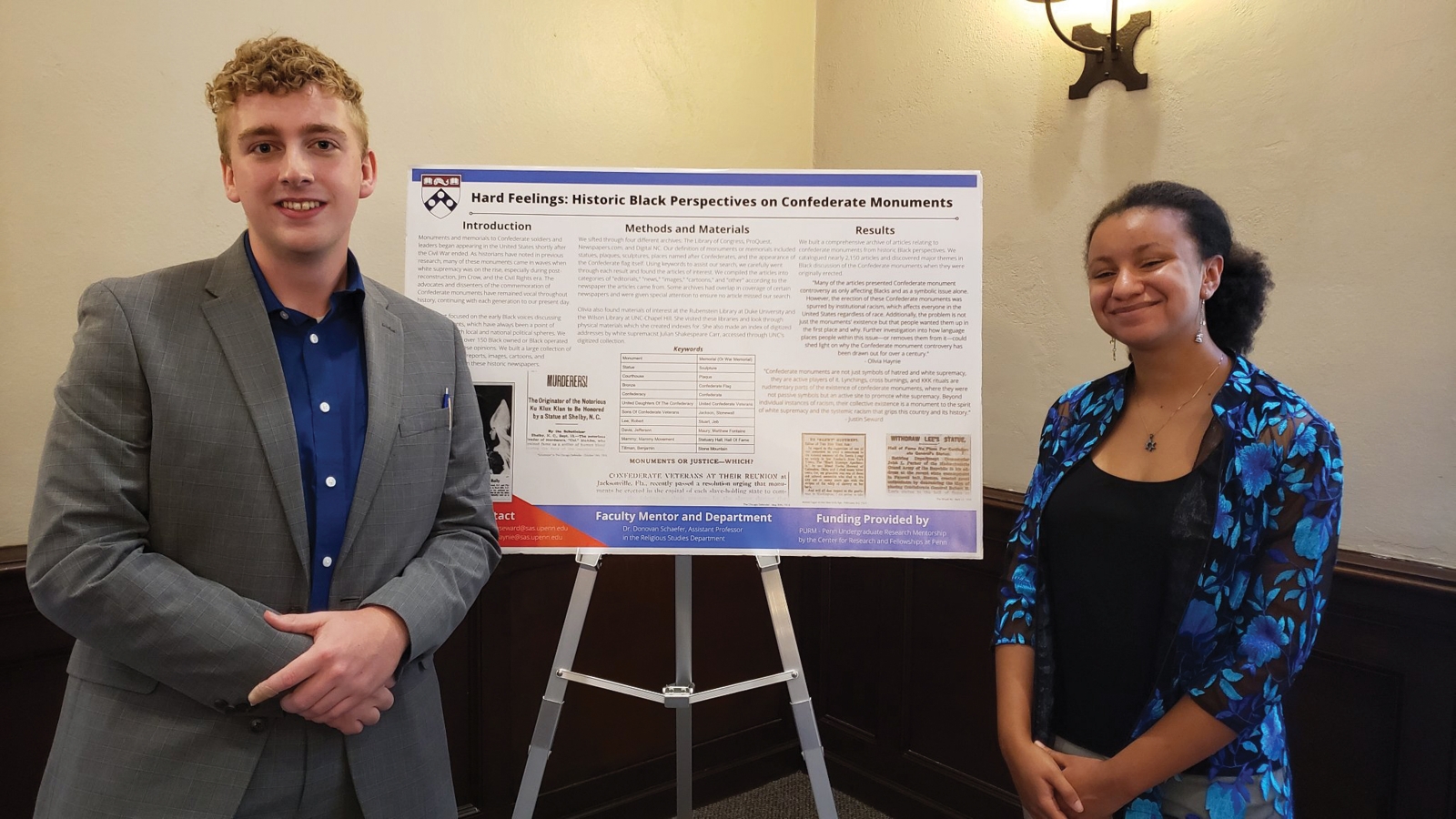

Olivia Haynie, C’24, and Justin Seward, C’25, spent the summer researching historical Black perspectives on Confederate monuments.

Hundreds of white nationalists and Neo-Nazis descended on Charlottesville, Virginia in opposition to the removal of a Confederate statue in 2017. Media images showed the group marching through the University of Virginia campus with lit torches, waving Confederate flags in the town, and later, the aftermath of the death of a counter-protester mowed down by a white supremacist in his car. Since then, other instances of Confederate monumentation like the carvings at Stone Mountain, the Confederate flag flying over the South Carolina State House, statues of Confederate generals across the country, and many others—alongside the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement—have sparked ongoing anger, debate, and controversy across the United States.

While it may seem like the issue of Confederate monumentation has only recently been brought to the fore, the controversy surrounding these monuments long pre-dates the modern day, say Olivia Haynie, C’24, and Justin Seward C’25. In particular, the Black community has been writing and speaking on the topic of Confederate monuments since their construction began shortly after the Civil War—though their voices have been largely marginalized and unexplored, the duo says.

Through the Penn Undergraduate Research Mentoring Program (PURM), Haynie and Seward spent the past summer researching Black opinions on the topic of Confederate monuments in more than 150 Black-owned or -operated newspapers. They were advised by Donovan Schaefer, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, with whom they’d recently taken the course Sacred Stuff: Religious Bodies, Places, and Things.

Under Schaefer’s guidance, Haynie and Seward defined monuments as statues, plaques, sculptures, places named after Confederates, and the appearance of the Confederate flag itself. They examined 2,150 articles and 600 addresses, including news reports, images, cartoons, and advertisements cataloged from the online archives of The Library of Congress, ProQuest, Newspapers.com, and the Digital NC database (a project of the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center), from the immediate aftermath of the Civil War until today. Additionally, Haynie, a CAMRA Mellon fellow who is majoring in sociology with a minor in religious studies, spent time in the physical archives at UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke University. Haynie notes that touching physical documents from the past was interesting, but also emotional. “At UNC, I handled a Confederate scrapbook of articles and memorabilia that someone had put together. It was fascinating to try to put myself into the shoes of someone who is so different from me,” she says. “My father grew up as a Black man in rural North Carolina where the Klan would march with Confederate flags in the Christmas parade. That was part of the hometown tradition. So, obviously it’s a personal thing for me. It was startling to handle documents—to read and realize more fully what my family went through.”

The student-researchers found upticks in Black commentary on Confederate monumentation during specific historical time periods like the post-reconstruction era, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights movement. Largely, the commentary was critical of any Confederate monumentation, but there were differences of opinion on certain types of monuments. Haynie says, “some of the ‘Mammy’ monuments or monuments to the ‘loyal slave’ during the Civil War were seen by some Black people as good because they might be good for the perception of Black people, for example. Or differences in opinions on more modern monumentation like the Confederate flag flying over the South Carolina State Capital and the NAACP encouraging a statewide boycott—some Black people felt the NAACP should leave it alone because there are bigger fish to fry, so to speak.”

Seward, who is double majoring in sociology and religious studies, says the research reinforced that “Confederate monuments are not just symbols of hatred and white supremacy, they are active players in it because they perpetuate white supremacy.” And although he finds the “emotion and call to action” surrounding the modern conversation hopeful, he did see similarities between today’s debates and those around the time of the Civil Rights movement, calling into question how much movement has been made.

During the research process, Seward dug deeply into the long and storied development of the carvings of Confederate imagery on Georgia’s Stone Mountain—the largest Confederate monument in the world. “Conversations about the carvings began in 1906-07 and it took over 60 years to finally complete them in 1972, with lots of contention and drama throughout,” says Seward. The carvings depict the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, and Confederate Generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee on horseback. Seward adds, “There was a lot of controversy over Stone Mountain’s imagery from conception to its final completion. There were varying political opinions coming from whites in the North and the South and Black people throughout the country, and I was struck by how a lot of the writings sounded like they could be modern New York Times op-eds.”

For Haynie, the research also highlighted how much the conversation hasn’t shifted much at all, and that Confederate monumentation continues to be presented as a problem that only impacts Black people. “It’s frustrating to read articles from over 100 years ago and feel like the language and framing hasn’t changed. Many of the historical articles presented Confederate monuments as only affecting Blacks and as a symbolic issue alone. However, the erection of these monuments was spurred by institutional racism, which affects everyone in the United States regardless of race.” She adds, “It’s becoming more common for people from all backgrounds to be against Confederate monuments, but the way we're discussing the problem really hasn't progressed; it feels like we’ve been treading water.”

The next stage of this research will be to identify a methodology to analyze and code the contents of the articles, says Seward, a Benjamin Franklin Scholar, Penn Civic Scholar, and E. Digby Baltzell Scholar of Sociology. He will continue working with Schaefer this upcoming summer, while Haynie is not yet sure of her summer plans. The pair anticipates that the documents will eventually be available to the public through a digital archive.

Haynie, who is particularly interested in audio ethnography and film, is hopeful that “further investigation into how language places people within this issue—or removes them from it—could shed light on why the Confederate monument controversy has been drawn out over a century.”