“My mother’s whole crowd she used to hang with died of cancer. Like come on. No way … Her, my step-dad, the neighbors around the side, the neighbors across the street … everybody was dying back to back …”

The typed note was pinned to a cork board inside a basement meeting room in the Donatucci Library in South Philadelphia, where city residents gathered along with climate activists, public health advocates, artists, and Penn students on a frigid December day to talk about the Philadelphia Energy Solutions Refining Complex (PES). An explosion and fire on June 21, 2019, had resulted in the shuttering of the 150-year-old refinery, leaving the site and its surrounding communities with an uncertain future.

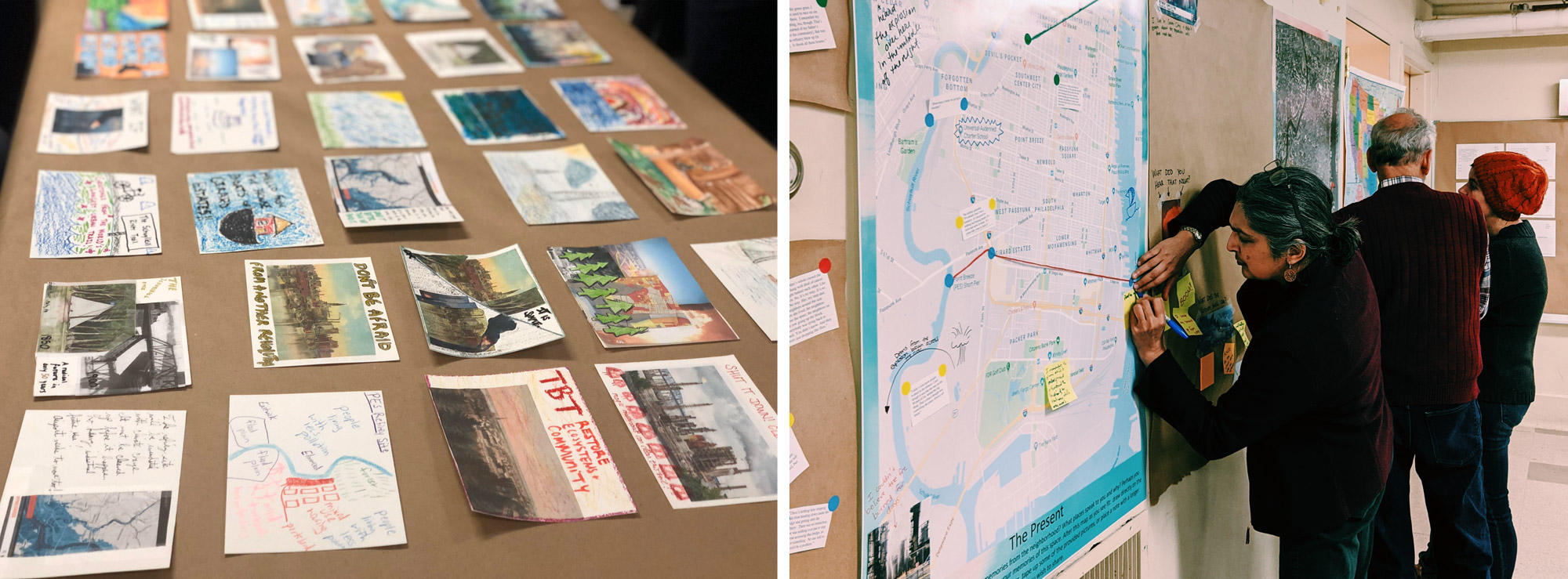

The meeting was part of a day-long event that included guest speakers, an arts-based visioning workshop, and community-led tours of the Gray’s Ferry neighborhood, which sits just to the north of PES. The day’s programming was part of a long-term project called “Futures Beyond Refining.” It was designed by students in a fall 2019 graduate seminar called Environmental Humanities: Theory, Method, Practice, taught by Bethany Wiggin, Associate Professor of German and Founding Director of the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities (PPEH).

Now in the third year of a four-year pilot grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, PPEH focuses on interdisciplinary, collaborative research; public engagement; raising awareness of environmental issues through collaboration with creative artists; and building a digital archive. The program supports Penn faculty in developing new courses and projects that extend the reach of environmental study. In fall 2020, PPEH will begin offering an undergraduate minor. Read more about PPEH.

As an example of community-based participatory research—in which universities and other institutions partner with community members who have a stake in the research process and findings—Futures Beyond Refining was designed to have a tangible impact on the Gray’s Ferry neighborhood.

“One of the things that we in PPEH have said from the very beginning is that we’re challenging the notion of what it is to study the environment,” says Wiggin. “It’s not just about remote forests or mountain peaks, or the supposedly pristine places thought of as ‘nature’ apart from humans. In fact, we’re interested in waterways and landscapes in which humans are very much a part. We’re thinking through the connections between environment, social justice, and public health. And we hope that by working together—often with the help of artists and writers—we can shine a light on the interdependence of human and environmental health to galvanize attention in this era of climate and ecological crisis.”

Each of the students in Wiggin’s seminar had a role to play in the Futures Beyond Refining project, from finding a location to inviting speakers and participants to publicizing the event. Wiggin and the students made contact with neighborhood activists and residents through a local group called Philly Thrive. Most students partnered with a Gray’s Ferry resident to collect and record oral histories. The residents told of profound health impacts from living so close to the largest refinery on the East Coast, including high rates of asthma and cancer, as well as a lack of timely information about the plant’s emissions and the effects of the June explosion.

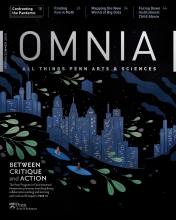

The oral histories will form the basis of a digital tour and mapping project of Gray’s Ferry that captures and amplifies people’s wishes and desires for the future, says Wiggin. “The project will consider the burdens that people have lived with and will continue to live with, and that certainly would be exacerbated if refining continues.”

DIALOGUE ACROSS DISCIPLINES

The students in Wiggin’s PPEH seminar entered the class with a range of interests and experiences. They began the semester with readings and research on other “fence-line communities” located near industrial sites. The students designed the Futures Beyond Refining project to explore the historical relationship between PES and its surrounding neighborhoods, disseminate data on impacts, and engage residents in imagining alternative uses for the site—literally a “future beyond refining.”

“We thought about the ways that energy infrastructure like PES so radically changes not only the land it’s built on, but also its surroundings through pipelines and transportation systems,” says Wiggin. “We wanted to understand the cultures that grow up around this massive infrastructure.”

We want our students to grapple with complexity and the complicated histories feeding the natures and cultures we inhabit together.

Alexandre Imbot, C’20, the only undergraduate in the course, majored in environmental studies with a concentration in sustainability and environmental management. He had prior experience in public outreach thanks to an academically based community service course called Community Based Environmental Health, taught by Marilyn Howarth of the Perelman School of Medicine—another member of the PPEH faculty working group.

Imbot is convinced of the importance of personal narrative. “It’s about asking people to share their ways of knowing and being with the refinery, beyond just hard numbers,” he says. “What does it smell like? What has been constant living here and what has changed?”

For his senior thesis, Imbot continued to build on the Futures Beyond Refining project by assessing how ethnography and community-based participatory research can create meaningful space for local knowledge in measuring the risks of large polluting facilities.

“I think one of the most powerful parts of the class was that everybody came from such different backgrounds,” he says. “We all had different ways of approaching the same material and the same issues when planning this project.”

A fourth-year student in the Perelman School of Medicine, Berryhill McCarty, G’21, M’21, is taking time away from her medical studies to earn a master’s degree in English through Penn Arts & Sciences. The move is part of her interest in medical humanities, a growing field that includes the humanities, social sciences, and the arts and their application to medical education and practice.

“I decided to take Bethany’s class because the environmental humanities is very similar to the medical humanities and because the environment is so inextricably linked to human health,” McCarty says. “We’ve seen again and again in history the need to understand the environment our patients live in.”

We spent the first month of the semester living in the critique space, doing a lot of reading, and then once we had that background, we began putting our knowledge into action.

McCarty was intrigued by one of Wiggin’s favorite descriptions of environmental humanities: “Bethany told us that the ‘environmental humanities inhabits the space between critique and action.’ We spent the first month of the semester living in the critique space, doing a lot of reading, and then once we had that background, we began putting our knowledge into action.”

McCarty created maps showing the refinery site in the 1800s, the present day, and in the climate-changed future when sea level rise will be even more apparent across South and Southwest Philadelphia. “The December event wasn’t just about the health data or the air quality data that some of the guest presenters spoke about,” she says. “It was also about telling the story in such a way that will engage the community and get people to care.”

Meredith Hacking, a doctoral student in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, studies medicine, food, consumption, and appetite in German literature with a special focus on plant matter and ideas of healing. For her, the project resonated with her interest in health and what people take into their bodies.

Hacking is a Philadelphia-area native who grew up exploring the Wissahickon Creek, one of the tributaries of the Schuylkill River. “In Bethany’s class we thought very carefully about climate change right now,” she says. “What are the different perspectives on what is happening to the lowlands around the Schuylkill River and how is our knowledge incomplete? What other perspectives do we need to bring in?”

Hacking interviewed community activist Charles Reeves, who led one of the neighborhood tours in December, and recorded his memories about growing up as an African American in Gray’s Ferry during segregation. The two held a long conversation on a small bridge where Reeves said he played as a child.

What’s Your Climate Story?

To collect and record lived experiences of climate change, the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities (PPEH) is building a digital story bank with a project called “My Climate Story.” Planetary warming is documented by atmospheric and ocean sensors, but My Climate Story recognizes that human sensations also provide important data for sharing and understanding localized impacts around the world.

Bethany Wiggin, Associate Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures and Founding Director of PPEH, and several of her students presented their own personal narratives as part of the Penn Arts & Sciences 1.5 Minute Climate Lecture series, held weekly last September in front of College Hall. The storytellers told of dropping water levels in Oregon’s Willamette River, severe drought and water shortages in South Africa, and heat waves in Wisconsin. Wiggin herself recalled growing up in Maine, where the ocean was too cold for swimming when she was a child, but is no longer.

To browse stories or record and submit your own climate story, visit stories.datarefuge.org.

“I wondered, why would kids be playing on a bridge over railroad tracks next to a refinery?” says Hacking, “and it’s because the Black kids could not use the local playgrounds. The area was segregated.”

Wiggin’s seminar aligned with Maggie McNulty’s interests as well. A student in Penn’s Master of Environmental Studies program, McNulty first heard about PPEH as an undergraduate at Drexel University, where she earned a degree in environmental studies and sustainability.

“The Futures Beyond Refining project was a great way to engage with the public outside of the classroom,” McNulty says. “As an undergraduate, I did ethnographic research and assisted a professor with interviewing people who lived in southwest Philadelphia regarding flooding and mold in homes—related to climate change specifically—and the subsequent health impacts.”

Her community partner was Melissa Toby, and McNulty got to know Toby’s entire family and their concerns: “In talking to Melissa, what she really wanted to accomplish through this partnership was for us to really understand what it’s like to live there.”

Wiggin’s seminar continued this spring, conducted online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two students worked remotely with neighborhood residents to gather additional narratives and help establish the tours as a permanent community resource.

“When you’re doing community-based participatory research, an academic semester doesn’t mean anything to our partners, so you can’t build projects solely driven by one class,” Wiggin notes.

PPEH public events and activities continued digitally as well, including initiatives exploring the confluence of pandemics and climate change, a full slate of Earth Week presentations, and an international conference in May titled “Climate Sensing and Data Storytelling.” Wiggins gave a presentation contextualizing the Futures Beyond Refining project in terms of public health. “Moving the conference online gave us an opportunity to try out the Nearly Carbon Neutral digital platform developed at UC Santa Barbara,” says Wiggin. (Recorded presentations from the conference are available at climatesensing.org.)

Learn more about the Futures Beyond Refining project:

WHAT THE ARTS CAN DO

Storytelling and other creative arts are key avenues of exploration for PPEH, and each year the program engages an artist-in-residence. In 2019, the visiting artist was filmmaker, multimedia artist, and Temple University professor Roderick Coover.

For nearly 10 years Coover has kayaked along both shores of the Delaware River from the Delaware Bay to the falls at Trenton, creating online maps of the heavy industry lining the shores that indicate future water incursion levels at these facilities if climate change remains unchecked, with implications for the river’s health. His project, “Altering Shores,” was performed last November at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts. It featured words and images projected onto translucent screens while 20 “unscripted performers”—including Wiggin—walked among the projections.

“The images were text heavy and included words like ‘toluene’ [a benzene derivative] and a ton of chemical symbols,” says Wiggin. “As you walked around the screens these chemical names and symbols were projected onto your body. It wasn’t until I was immersed in that performance that I realized—we’re all living in a chemical bath.”

Wiggin says creative expressions like Coover’s project provide a vital mechanism for understanding problems like climate change that can seem too overwhelming for people to fully comprehend and respond to.

“We’re living in a time and a reality that is so difficult to understand,” she says. “The vision that creative people bring can be more instructive than a sober analysis of data. The scale and size of what we’re in and what we’ve caused exceeds, I think, our human capacity for realistic representation, and these experimental projects are ways of describing a very complex reality.”

Understanding the complex reality of human interaction with the environment through different modes of inquiry, and using that knowledge to make a difference, are the central tasks of environmental humanities.

Says Wiggin, “We want our students to grapple with complexity and the complicated histories feeding the natures and cultures we inhabit together.”

Public Research Internships

One of the ways the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities (PPEH) engages students outside of the classroom is through public research internships that follow two tracks: storytelling and finance.

Alex Imbot, C’20, helped create a de-carbonized investment portfolio as part of a climate finance internship, a joint initiative between PPEH and the Wharton School. The “Sustainable Investment Portfolio Challenge” calls on students at Penn and across the country to identify ways that university endowments can invest in less environmentally harmful industries while remaining profitable. Wiggin was eager to have the climate finance interns document the process and interview investors. Imbot explains, “We’ve built a website about climate finance, looking at what is the role of investment in terms of a path toward a cleaner, de-carbonized future.”

Urban studies major Piotr Wojcik, C’20, was a PPEH storytelling intern, part of a team that helps produce the PPEH podcast and blog, “Data Remediations,” and supports the My Climate Story project. Wojcik attended the Futures Beyond Refining program last December to record interviews for the podcast. Community engagement was not new to him. Last summer, he held an internship with the Heidelberg Project, a public art project in Detroit that called attention to vacancy and neighborhood disinvestment.

“Because of my interest in storytelling and public engagement through the arts and humanities, and how they intersect with environmental issues and political organizing, this internship was perfect,” Wojcik says. “Whoever has control over the story ends up having power in imagining the future. When we imagine ‘futures beyond refining,’ it’s about leveraging Penn’s institutional resources to raise the voices of the people.”

More About the Penn Program In Environmental Humanities

The Futures Beyond Refining project is typical of the multi-modal, immersive approach embraced by the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities (PPEH), which grew out of student demand for environmental dialogue across disciplines. The growing field challenges the idea that environmental studies should be situated only within quantitative and natural sciences. The PPEH faculty working group includes professors from across Penn Arts & Sciences—representing traditional partners like earth and environmental science and biology, but also anthropology, sociology, history and sociology of science, cinema studies, and English—as well as the Perelman School of Medicine, the Wharton School, and the Stuart Weitzman School of Design.

Daniel Barber, Associate Professor of Architecture in the Weitzman School, serves on the PPEH faculty working group. “We are accustomed to working across disciplinary boundaries to understand the contours of an urban or landscape situation,” he says. “Collaborating with other schools greatly enhances this process, providing a rich knowledge base to students and helping them see the broader context of their design interventions. At the same time, the strategies and methods of design contribute to explorations in other schools, providing visual and representational tools and offering new perspectives.”

Each year, PPEH courses, projects, and events revolve around a central theme or topic with a rotating faculty director. (Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many events this spring were held virtually.) Nikhil Anand, Associate Professor of Anthropology, served as director for the 2019–2020 topic, “Elements.” It references the four elements of fire, water, earth, and air, which many traditions hold as central to the composition of both human character and the world. “The topic was organized around re-thinking the elements going forward,” says Anand. “We looked at what we might make of them now that they have been shaped and altered through different human projects to control them.”

Barber will lead next year’s topic, “Transition/Transformation.” It will explore ways to effect a transformation to a world less dependent on fossil fuels, looking beyond changes in technology and behavior toward creation of a society that is more equitable and less carbon intensive.

PPEH engages with other universities and research partners through conferences and information sharing. Its global reach is illustrated by a multi-year collaboration between Wiggin and Anand called “Rising Waters: Philadelphia and Mumbai.” The project studies the threats posed by rising sea levels in these two port cities, each characterized by significant amounts of landfill that have transformed wetlands into dry land, where industrial infrastructure often sits in proximity to low-income communities.

“In both cities, people living in the social, political, and economic margins have been pushed to the spatial margins of the city through evictions and displacement,” Anand says. “Industry is simultaneously occupying these marginalized, infilled lands, so both Philadelphia and Mumbai share a history of people being thrown into harm’s way.”

Kristina Lyons, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, is affiliated with the Latin American and Latino Studies program (LALS) and PPEH. She joined Penn in August 2018 in a faculty hire designed to grow the School’s strength in the environmental humanities.

“PPEH was one of my main reasons for coming to Penn,” says Lyons. “I was really excited about the program’s emphasis on public engagement and interdisciplinary collaborations between the social and natural sciences and the arts and humanities. PPEH is creating generative and exciting opportunities for faculty, graduate, and undergraduate students, both at Penn and internationally.”

Lyons’s research focuses on the intersections of socio-ecological conflicts, justice and reconciliation, and feminist science studies in Colombia. “I’m hoping to participate in creating a bridge between PPEH and LALS,” she says, “and that we can generate opportunities to address socio-environmental issues within and across the hemisphere, the Americas.”

For more information about the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities, including video, podcasts, online resources, and events, please visit ppehlab.org.