Impressionism and the Modernization of Time

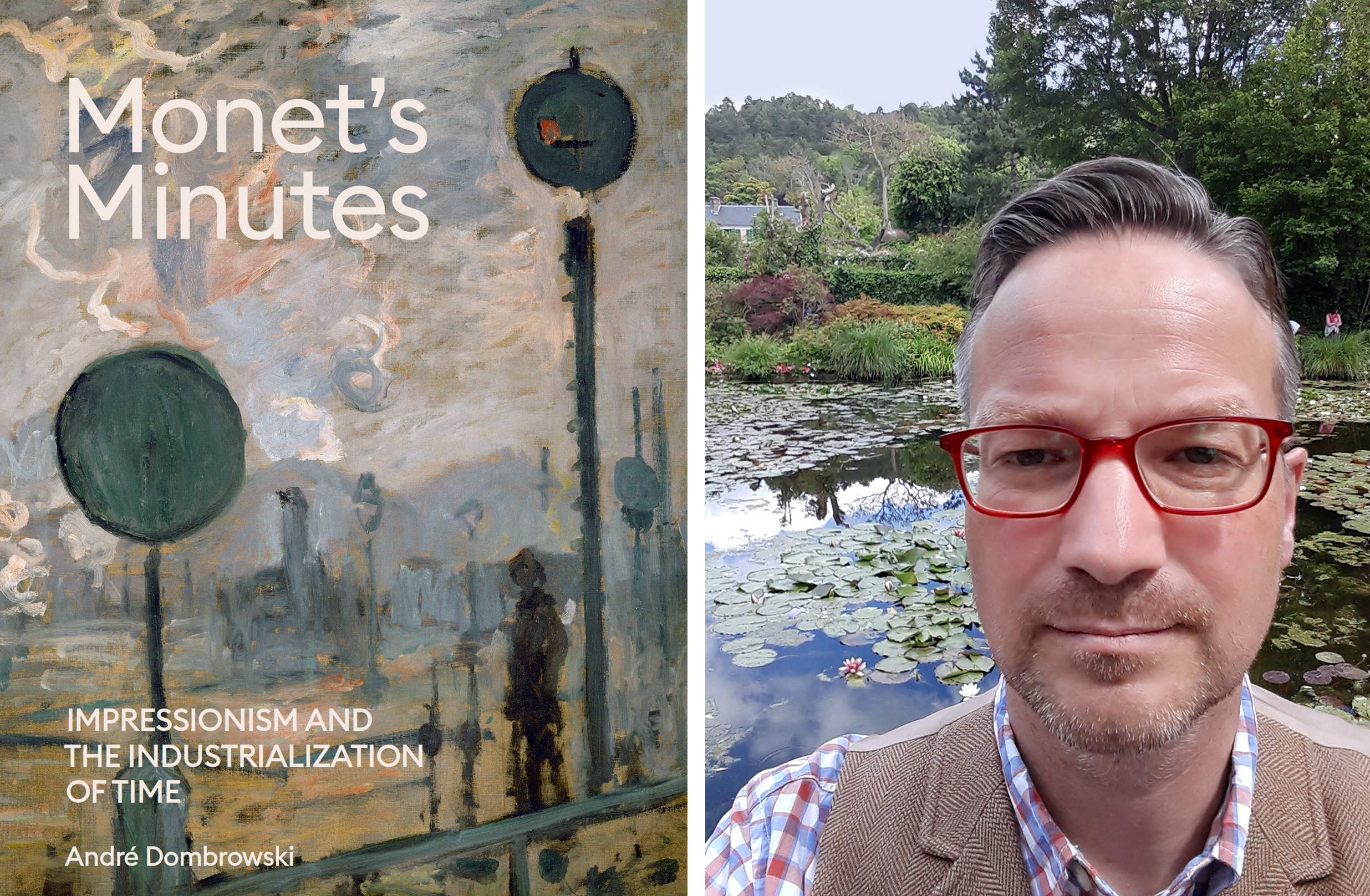

A new book from History of Art Professor André Dombrowski knits together the works of artists like Claude Monet and the nature of time as it emerges in its present-day form.

For many Impressionist painters, capturing a fleeting moment—what’s known as “instantaneity” in Claude Monet’s own words—became a popular theme for their work, especially during a period in history when society was grappling with the emergence of modern timekeeping.

In his new book, Monet’s Minutes: Impressionism and the Industrialization of Time, André Dombrowski, Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Associate Professor of 19th Century European Art in History of Art delves into the subject, arguing that Monet’s celebration of instantaneity was more than just a simple aesthetic choice. Rather, it was deeply rooted in the shift during Monet’s lifetime toward a world increasingly concerned with keeping accurate time and the technologies invented to do so.

Inspiration for Dombrowski’s new book came when he was teaching a course on Impressionism. He realized the parallels between the major dates of the movement and the development of modern timekeeping.

The book’s inspiration came to Dombrowski while studying the early work of Paul Cézanne, particularly a painting called The Black Clock that led him to consider, and read extensively on, the history of time and timekeeping technology. “I came across a book that is absolutely fantastic, by Peter Galison, called Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps, about the relationship between modern bureaucratic time and the theory of relativity. At the same time, I was teaching an undergraduate lecture course on Impressionism. Going through the major dates associated with Impressionism, I was realizing just how incredibly parallel they were to the development of modern timekeeping,” he explains.

The birth of Impressionism, an art movement focused on capturing the transient effects of light and color in the natural world and widely known by the work of artists like Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, occurred in the mid-1860s, with the first major exhibitions in the 1870s. The movement marked a significant departure from the traditional, detailed, realistic representation of subjects previously prevalent in art.

Around the same time, the world started reconsidering the nature of time. In 1865, Dutch physiologist F.C. Donders began to think about reaction time in humans—the quickness with which our organism responds to a stimulus—and whether it was measurable. In 1877, a clock contest was held in Paris to standardize and coordinate the major Parisian clocks, and a few years later in 1884, in Washington, D.C., nations around the world voted to establish Greenwich as prime meridian and create what eventually would become the modern global time zones. In 1886, the final of eight Impressionist Exhibitions occurred.

In the book, Dombrowski knits together the two histories to unearth their concrete interactions and intersections. Monet is his central player, an example of an Impressionist artist who had a “sophisticated, beautiful, stunning response to the emergence of these developments in time management,” Dombrowski says. “Monet really registers this profound change toward a much more artificial, cultural, standardized approach to time.”

Alumni Learners

In 2023, more than 150 learners logged in from 14 countries and various time zones to hear a three-part seminar by History of Art Professor André Dombrowski on the overlap of Impressionism and the modernization of time. The seminar, called “Monet Painting Time,” was sponsored by the Penn Alumni Travel Office, part of an effort to highlight new research and publications from faculty for an alumni audience, and gave participants a glimpse into Dombrowski’s new book, Monet’s Minutes, published in November 2023.

For example, Monet painted laborers carrying coal to shore in a very orderly manner; it was around this moment that standardization of time and the workday started coming into play around labor. “It’s an excellent example of a truly temporally regulated painting that isn’t seen in the same way in his other works,” explains Dombrowski, whose book also discusses Monet’s paintings of trains and train stations, with their newly exacting schedules, and his “series” paintings that depicted one subject, like a haystack, seen during many different times of day or seasons.

Though modern audiences think of Impressionism as an “utterly pleasant style, about sunshine and beach vacations and lovely colors,” Dombrowski says that at the time Impressionism emerged, it was not overall well received, mostly panned by critics, and commercially unsuccessful.

Artists like Monet were compelled to create paintings that felt like “they were over in an instant, that pretended they showed nothing but a gust of wind or a ray of sunshine,” Dombrowski explains. “My book asks, ‘Why did paintings emerge at this time that pretended to be quick on all kinds of levels—quickly painted, and showing very insubstantial, very brief moments in time? Where does all this time pressure in painting come from?’” Dombrowski argues it’s partially because such artists were influenced by, but also partly rejecting, the blunting reality of newly routinized, standardized, and universalized time.

Dombrowski says he hopes readers come away with a different understanding of Impressionism, one rooted in the context of time habits shifting from more natural ones, like rising with the sun, to what exists today, a clock- and schedule-based standard and uniform time that garners almost universal agreement regarding its function, meaning, and value.