The Poetry Industrial Complex

Lecturer in Critical Writing Amy Paeth’s new book uses the history of the U.S. poet laureate as a window into how the arts, government, industry, and private donors interact and shape culture.

In the 1940s and ’50s, U.S. poets Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell traveled around the world as “cultural missionaries,” funded by grants from the Rockefeller Foundation but also the Farfield Foundation and the Congress for Cultural Freedom, both fronts for the CIA. When the Iowa Writers’ Workshop created its international program in 1967, it also received funding from the Farfield Foundation, as well as the U.S. State Department.

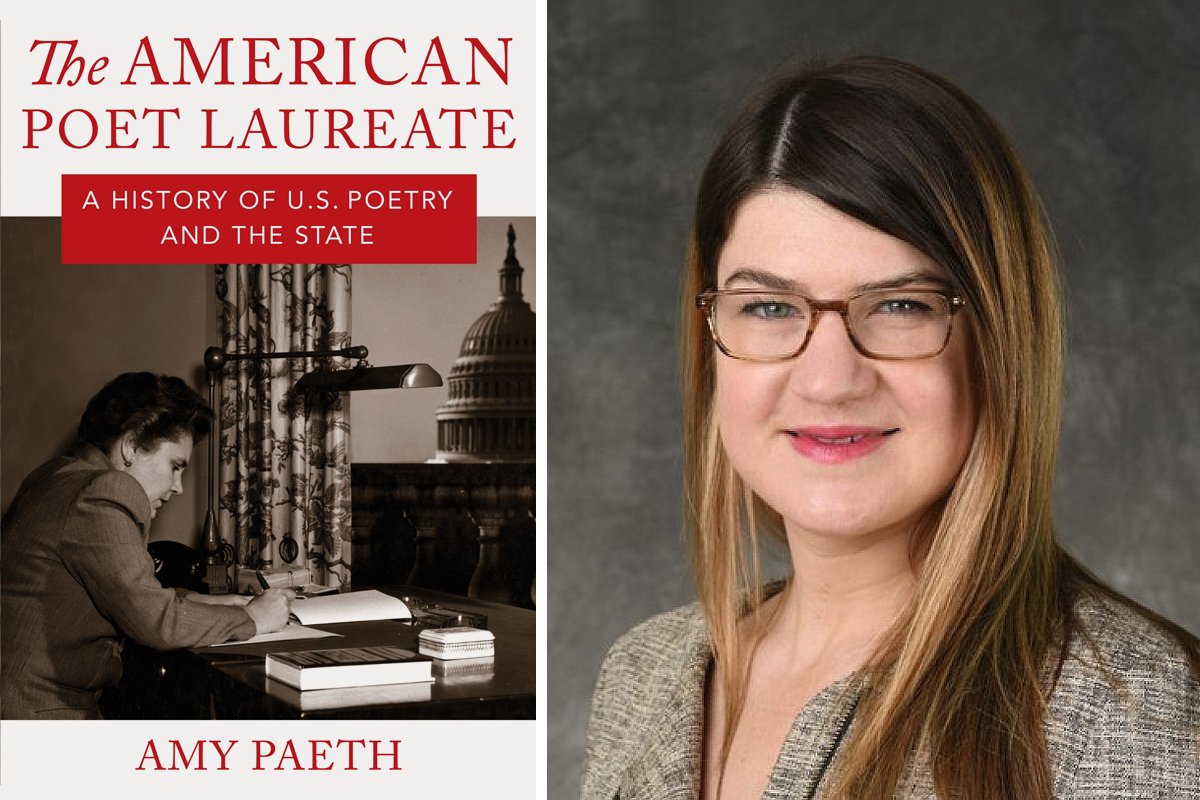

In her new book, The American Poet Laureate: A History of U.S. Poetry and the State, Lecturer in Critical Writing Amy Paeth, GR’15, uses the office of the U.S. poet laureate as a lens to illuminate the state’s influence on poetry—and vice versa—since World War II. The book received the Northeast Modern Language Association’s Annual Book Award and accolades from the Times Literary Supplement.

It is the first history of the national poetry office and the position now commonly called the U.S. Poet Laureate, held by Bishop and Wallace, Robert Frost, Gwendolyn Brooks, Robert Pinsky, and Tracy K. Smith, among others. But Paeth’s picture is bigger, showing how poetry has played a uniquely important and largely unacknowledged role in the cultural front of the Cold War.

Your Tax Dollars at Work

Paeth says the office has always been an example of how the state uses its resources. In the beginning, the job title was “Consultant in Poetry in the English Language at the Library of Congress.” “It was a weird little custodial endowment and people hung out there a little bit, maybe wrote some poems, but it was just a cushy situation,” says Paeth.

After World War II, the office became increasingly politicized. Controversies followed the awarding of the Bollingen Prize for Poetry (then chosen by Library of Congress fellows) to Ezra Pound and, later, the appointment of William Carlos Williams as the Consultant. Both were rescinded because of the recipients’ politics.

Paeth describes the Kennedy administration as a “huge breaking point” in the office’s history. Frost delivered the first-ever inaugural poem, and Kennedy sent him to Russia, where he met with Nikita Khrushchev, first secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. While there, Frost declared, “A great nation makes poetry, and great poetry makes a great nation.”

“Poetry had this new elevated value in the field of ideas, especially of what it meant to be a citizen, what the nation was, and during the Cold War it all becomes more important,” Paeth says. “Robert Frost saw poetry as an analog for national values. He really thought about how we use speech in poetry, what poetry stands for, the way we feel when we’re reading a poem—all of that has to do with who we are as citizens.”

Poetry also became personal. “The individual voice became very important as an idea in the American nation. The poem, more than other art forms, really had the power to express the ‘I’ speaker,” says Paeth. “To this day that’s how we think about poetry in this country. It probably seems unremarkable to us, ‘Oh, yeah, a poem was talking about the personal,’ but that is actually very historically particular.”

That individual voice also found a home in the many post-war GI Bill-funded creative writing programs that sprang up. So, eventually, did government priorities. When the director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—still one of the preeminent programs in the country—contacted the government for support to create an international version of the program, the government was happy to oblige: another example of the expansion of U.S. global power through cultural programming. “American poets relied on state support, and thus served its interests in new ways during the Cold War,” says Paeth.

Into the Archives

As a scholar of poetry, Paeth didn’t expect to become an archival researcher. She began this work as a way of making sense of the difference between how she was trained as an undergrad at Princeton and as a graduate student at Penn, a result of the “poetry wars” of the 1980s and ’90s between mainstream and countercultural poets. “I found that the way I could make sense of the poetry wars was to explore these tensions between poets, styles, values, and publications from an institutional perspective,” she says.

It’s a lesson she shares with her students.

“The way you start out doing your research is not always how it will end up,” says Paeth. “I never expected to be sweating on the BoltBus going down to the Library of Congress. It turns out that it was actually really important to look at all of those physical texts and documents, memoranda, letters from secretaries, personal notes, personal correspondences. Those really shaped the story. You’re not just relying on what someone’s repeating from someone else. You’re diving down into the meat of what actually happened.”

She cautions students against trying to begin by finding a source to support their idea. “You have to go out and find out what really happened on the ground.”

Poetry and Power

During her research in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, Paeth came across a 1949 letter from Hayden Carruth, then editor of Poetry magazine, about his failure to secure a vital gift from the Lilly Foundation. Carruth was fired a month later.

More than 50 years later, in 2002, the Lilly family made a donation that shocked the nonprofit world, gifting $100 million to Poetry. The money resulted in a complete overhaul of the magazine’s structure and in the birth of The Poetry Foundation, “the most central institutional player, other than universities, in the field of American poetry today,” Paeth says.

When she found the 1949 letter, “I [wondered] what Carruth would have thought if he knew that five decades later, his requests for funding from the Lilly family would finally come through—in spades,” says Paeth. Because of the gift, Poetry magazine is now a part of “this huge infrastructure. It’s great, but it’s extremely corporate.”

By looking at institutional paper trails, Paeth shows how the state now does its funding work “most expertly through shifting constellations of private networks,” she says. “The way I see it, it’s a capitalist country, so to understand the interests of the state, you have to understand other interests and the way they’re funneling their interests.”

Despite the behind-the-scenes politics around the office, Paeth believes having a Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (as the office was retitled in 1986) is good for the nation, an encouragement to think about arts in everyday life. “Gwendolyn Brooks was a fantastic example of what the office can do,” Paeth says. “She occupied it from 1985 to 1986, right before it was retitled. She was a Black American poet from the Chicago south side, and she used her stipend to bring in different reading groups and host different things,” expanding a community focus that is now the major part of the position’s work.

State support of poetry or civic-minded poetry programming is not necessarily problematic, says Paeth, “but understanding the complex nature of the interests that create public-facing poets is increasingly important.” The commitments of individual poets laureate will be important to follow, she adds, as their programs and poems “teach us not about poetry but how we should be citizens.”