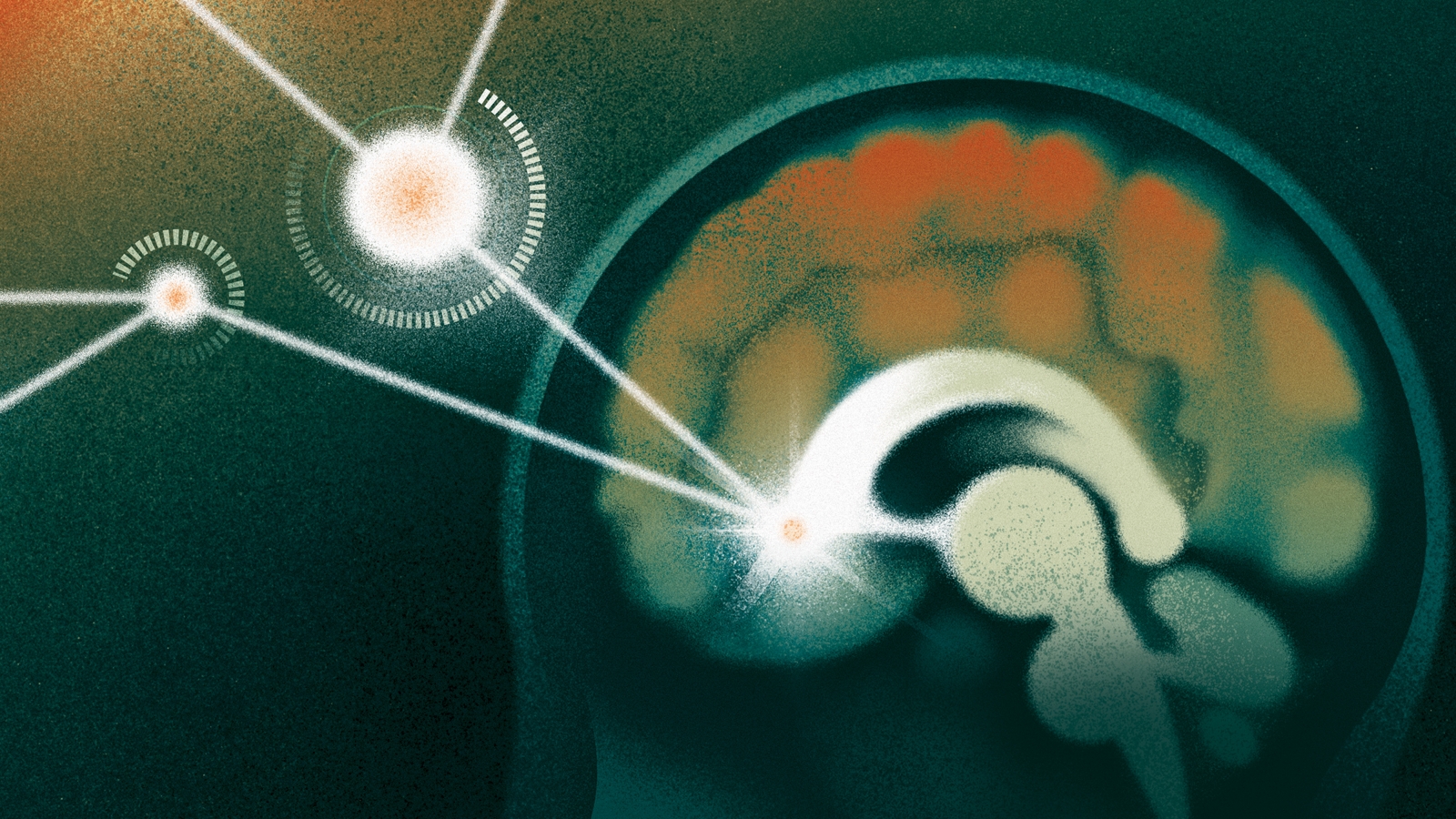

AI-Guided Brain Stimulation, Memory, and Traumatic Brain Injury

A collaborative study shows that targeted electrical stimulation in the brains of epilepsy patients with TBI improved memory recall an average of 19 percent.

Many people with a traumatic brain injury (TBI) struggle with short-term memory. Now a new study in the journal Brain Stimulation shows that targeted electrical stimulation could help, boosting word recall in such patients by 19 percent, on average.

A team of neuroscientists led by Michael Jacob Kahana, Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Term Professor of Psychology, studied TBI patients with implanted electrodes, analyzed neural data as patients studied words, and used a machine-learning algorithm to predict momentary memory lapses. Other lead authors included Wesleyan University’s Youssef Ezzyat and research scientist Paul Wanda, formerly in the Kahana lab.

“The last decade has seen tremendous advances in the use of brain stimulation as a therapy for several neurological and psychiatric disorders including epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, and depression,” Kahana says. “Memory loss, however, represents a huge burden on society. We lack effective therapies for the 27 million Americans suffering.”

Study co-author Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, director of the Perelman School of Medicine’s Traumatic Brain Injury Clinical Research Center, says the technology Kahana and his team developed delivers “the right stimulation at the right time, informed by the wiring of the individual’s brain and that individual’s successful memory retrieval.”

This new study builds on previous work of Ezzyat, Kahana, and their collaborators. In a 2017 Current Biology paper, they showed that stimulation delivered when memory is expected to fail can improve memory, whereas stimulation administered during periods of good functioning worsens memory. The stimulation in that study was open loop, meaning it was applied by a computer without regard to the state of the brain.

In a study with 25 epilepsy patients published the following year in Nature Communications, the researchers monitored brain activity in real time and used closed-loop stimulation, applying electrical pulses to the left lateral temporal cortex only when memory was expected to fail. They found a 15 percent improvement in the probability of recalling a word from a list.

The latest work specifically focuses on eight people with a history of moderate-to-severe TBI who were recruited from a larger group of patients undergoing neurosurgical evaluation for epilepsy. Seven of the eight are male, and Diaz-Arrastia says 80 percent of people who get hospitalized for traumatic brain injury overall are male.

Kahana emphasizes the importance of addressing TBI-related memory loss. “These patients are often relatively young and physically healthy,” he notes, “but they face decades of impaired memory and executive function.”

The researchers’ primary question was whether stimulation could improve memory across entire lists of words when only some words were stimulated, whereas prior studies only considered the effect of stimulation on individual words. Ezzyat says this development is important because “this suggests that an eventual real-life therapy could provide more generalized memory improvement—not just at the precise moment when stimulation is triggered.”

More work remains before this kind of stimulation can be applied in a therapeutic setting, and scientists need to study physiological responses to stimulation to better understand the neural mechanisms behind improved memory performance, Diaz-Arrastia says.

“These are still early days in the field,” he adds. “Eventually what we would need is a self-contained, implantable system, where you could implant the electrodes into the brain of someone who had a brain injury.”