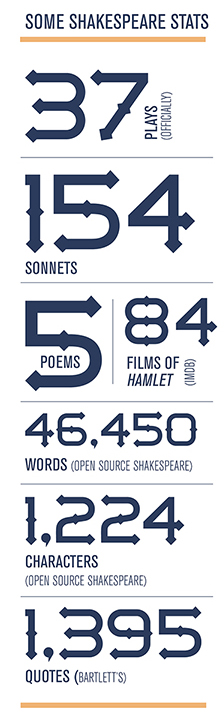

As of April 23, William Shakespeare has been dead for 400 years. The day came complete with its own hashtag, #Shakespeare400, and an emoji of the globally recognizable bald guy. But why do we care? When was the last time you read some Shakespeare on the train, or even saw one of his plays performed?

“One thing that’s remained constant over 30 years of teaching is that students think they know Shakespeare but are also intimidated by it,” says Rebecca Bushnell, School of Arts and Sciences Board of Overseers Professor of English, of the distance created by the works’ language, highbrow reputation, and some characterizations we now find repugnant.

One high school teacher recently caused an uproar by dropping Shakespeare from her lesson plan as irrelevant to her students. Others try to connect their pupils with his plays by studying the characters and their motivations “almost as if they’re real people,” says Bushnell, a past president of the Shakespeare Association of America.

Actors and directors have done the same, according to Cary Mazer, associate professor of theatre arts and English and author of Double Shakespeares, a history of contemporary performances, and the play Shylock’s Beard. Performances today include radical departures from the script, especially in international productions that may not feel limited by the famous language. One version interviewed middle-school students about Romeo and Juliet and acted out the responses, while another, Sleep No More, was staged in a warehouse. As audience members walked around the set they’d realize that the story was Macbeth, presented out of order and mostly unspoken.

“The plays are alive. They feel very present,” says Bushnell, whose books include A Companion to Tragedy and Tragedies of Tyrants: Political Thought and Theater in the English Renaissance. “But they were created at a particular moment in English and European history and they mean something in that context. We want it to be relevant, but we also want you to understand that it’s different from you, and that difference is interesting.”

“I think the students are very surprised, once we get more in depth, by some of the things that are happening in the plays and the strangeness of the Shakespearian world,” says Melissa Sanchez, an associate professor of English. The author of Erotic Subjects: The Sexuality of Politics in Early Modern English Literature, Sanchez cites scholars who say that most Europeans at that time still believed in the “one sex” model: that women and men had the same sex organs but inverted. “That meant that women and men were actually not so different, and theoretically women could become men and men women,” she says. “So when Lady Macbeth says ‘Unsex me here,’ she might mean that literally.”

Sexual norms were also different, with same-sex activities not specifically defined as gay or lesbian, and rape prosecuted as a property crime. Sanchez says, “The Shakespearian sexual world, much less all the other worlds that he represents to us, is not just this exciting and interesting and liberating world. It’s a very disturbing and troubling and upsetting world in a lot of ways.”

Instead of using history to contextualize Shakespeare, Margo Todd uses Shakespeare to teach history. The Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History specializes in early modern English and Scottish history and uses Richard III and Henry VIII in her classes. “Richard III is a great play, Henry VIII is not, but both are great historical pieces,” she says. Both works give a positive picture of the Tudors who ruled England; when Elizabeth I is born in Henry VIII, she is presented as a “heaven-sent princess.” “Shakespeare always had an eye to contemporary politics, not just to curry favor but to give warnings,” says Todd. “Richard III sends messages about what is legal and moral and what is not.”

In the 21st century, the digital humanities are giving us new ways to study Shakespeare using big data. These include stylometrics, a controversial approach to determining authorship by doing an analysis of style, grammar, and vocabulary. The arguments about whether or not William Shakespeare really wrote the works credited to him have subsided somewhat with the understanding that most dramatic writing at the time was done collaboratively. “It’s not what they show in Shakespeare in Love, with Joe Fiennes sitting up in his study writing about his relationship with Gwyneth Paltrow,” Bushnell says. “Instead you have this amazing culture of collaborative production of stories.”

Other recent approaches include ecocriticism, which examines the way the characters engage with the politics, social aspect, and aesthetics of nature; and the use of ideas from psychology and cognitive studies to look at what Shakespeare says about how our brains work. Bushnell herself is working on a book that connects tragedy in drama, film, and videogames. “Videogames have something to tell us about how tragedy works because they bring out the idea of being able to manipulate and control action and time, which is the heart of any classical tragedy,” she says. “While historical context is important, I’m also arguing that contemporary media can tell us something about the works of the past.”

English Professor Zachary Lesser will be considering these approaches and more as one of the three general editors of the fourth series of the Arden Shakespeare, a leading scholarly edition begun in the 1890s. “Students ask, ‘Oh, you work on Shakespeare. How could you ever come up with something new to say?’” he says. “But because Shakespeare’s so central to English literature, it means he changes constantly because the way we think about literature changes.”

The plays were written for a particular set of shared conventions and codes by which the audience understood the performance, Mazer says, and yet there’s enough there for later artists to appropriate material from which they can make their own theater pieces. “In Shakespeare the characters come to understand one another’s feelings by the act of empathy, and in the audience, whether or not we share values with them, we empathize with them.”

“Everybody knows him,” Bushnell sums up. “Some see that as a kind of global expansion and imperialism of English culture. I don’t, because one of the wonderful things you see when you look at what’s happened to Shakespeare over 400 years and the span of an entire globe is that everyone takes it and makes it their own. There’s something about that body of text in those plays that has a kind of power that people want to tap into, but they also want to adapt and possess and transform it. And I think that’s great.”

Penn’s Incredible Shakespeare Collection

Penn’s H. H. Furness Memorial Library contains virtually all English-language editions of Shakespeare’s plays and poems, including all four of the folios and even rarer materials such as Hamlet’s third quarto. Arts and Sciences Board of Overseers Professor of English Rebecca Bushnell helped to develop the virtual version of the library, but says, “For all of our ability to see everything on the Internet, the books themselves are still really powerful.

“For years I’ve taken my students in to see these books, and they’re blown away. The books embody the aura and power of the past, which they feel they can touch,” she says. “But recently I’ve realized I was in a new world because they all had their cell phones out and were taking pictures.”

Shakespeare Said What? (Online Exclisive)

All Shakespeare comes to us through at least one editor. “We don’t have any of Shakespeare’s manuscripts,” says Zachary Lesser, a professor of English who studies material texts. “We may have a page and a half of writing that may be his, that’s part of a play that was never printed and seems not to have been performed, but we don’t know. We only have the printed text.”

And the surviving printed text is far from reliable. Most of the plays were produced first as quartos, comparable to cheap paperbacks. In 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, his plays began to be put together in folios—larger and better-bound publications that were intended to last—but texts can differ greatly from version to version.

Lesser has written a book, Hamlet After Q1, about the uproar in 1823 following the discovery of the earliest-known edition of that play. Published in 1603, the text in this quarto was substantially different from the Hamlet that had become venerated in the meantime. One example: Instead of “To be or not to be: that is the question,” Hamlet says, “To be, or not to be, I there’s the point. / To Die, to sleepe, is that all?” Scholars today theorize that it might be an earlier draft or a pirated version.

The first quarto and first folio versions of King Lear also differ radically. The Norton Anthology of English Literature now prints both along with an editor’s conflated text. Other editions print the two versions on facing pages so readers can see differences at once.

Rebecca Bushnell, Arts and Sciences Board of Overseers Professor of English, says it’s impossible to think that somehow we could determine what the real King Lear was—something that unsettles students. “In close reading, we talk about why the author uses a particular word—and then you look at the notes and say, well, maybe he did and maybe he didn’t.”