Whatever You Say, Say Everything

Brendan O’Leary’s career, from aiding in the negotiating of peace in Northern Ireland to advising the Prime Minister of Kurdistan, has been guided by a simple principle: say exactly what you mean.

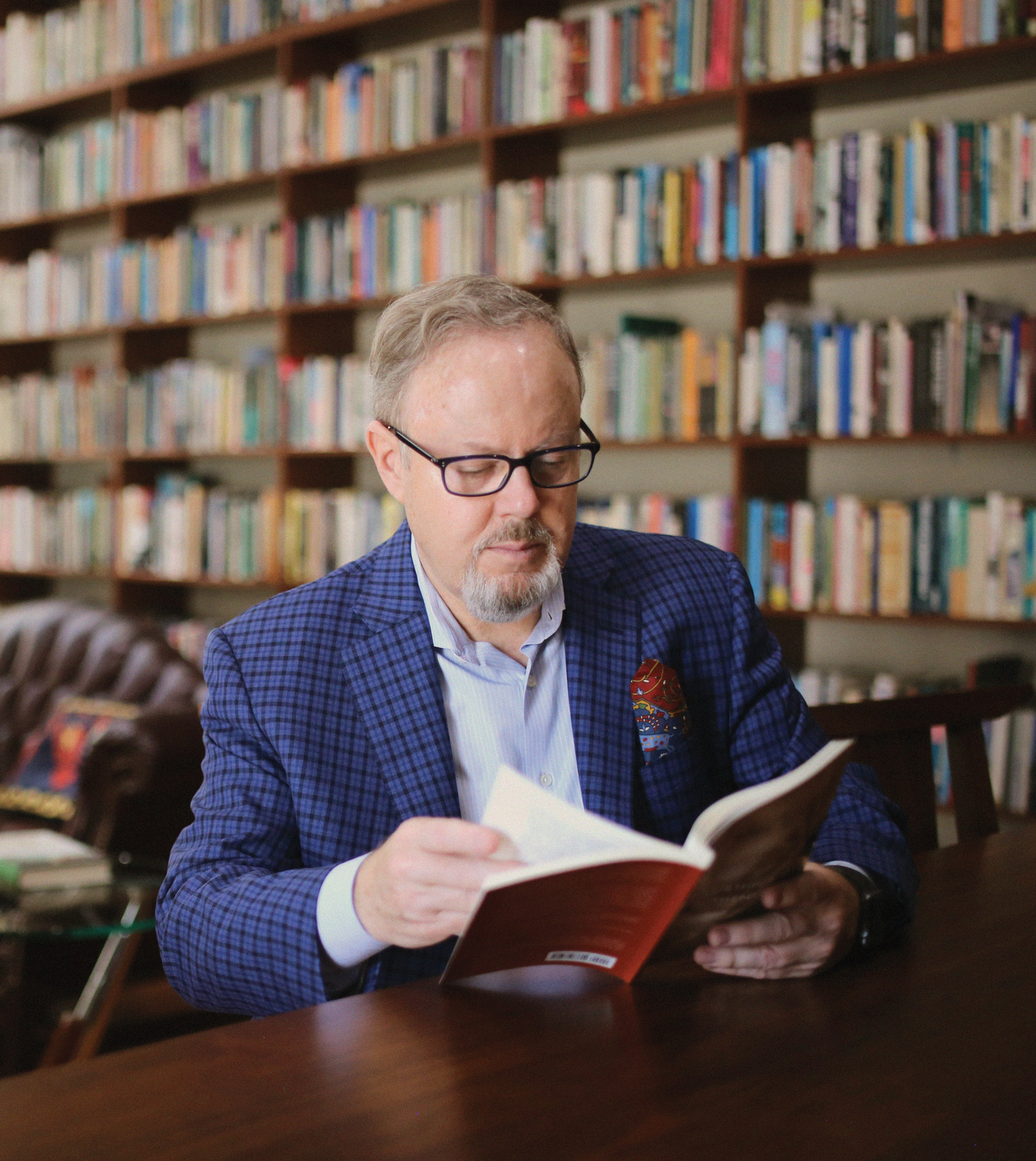

Brendan O’Leary is waging academic warfare. And trying his hand at comedy.

Both efforts are restricted to the endnotes in his recently published three-volume history of Northern Ireland. “After all,” he reasons, “you should be rewarded for going to the endnotes.”

O’Leary’s endnotes—the pages of annotations and explication that come after the main text—are where he dismisses a historian’s claims as lacking any textual justification and muses on folk memory in lyrics by Irish punk bands. But the endnotes aren’t the only unconventional part of this history. In the 1,240 pages of text, O’Leary’s training as a social scientist, as well as his commitment to thoroughness and his personal story, is present. For him, it’s a matter of principle.

I think it is incumbent on social scientists and historians to indicate where they come from, literally and figuratively, and how their views might potentially be challenged and how they might be wrong.

For the reader, it’s something that challenges typical treatments of Northern Ireland. It’s a history, but not written by a historian.

“I strongly believe in objectivity and reject the idea that everyone has their own facts,” O’Leary, Lauder Professor of Political Science, explains. “But, I think it is incumbent on social scientists and historians to indicate where they come from, literally and figuratively, and how their views might potentially be challenged and how they might be wrong.”

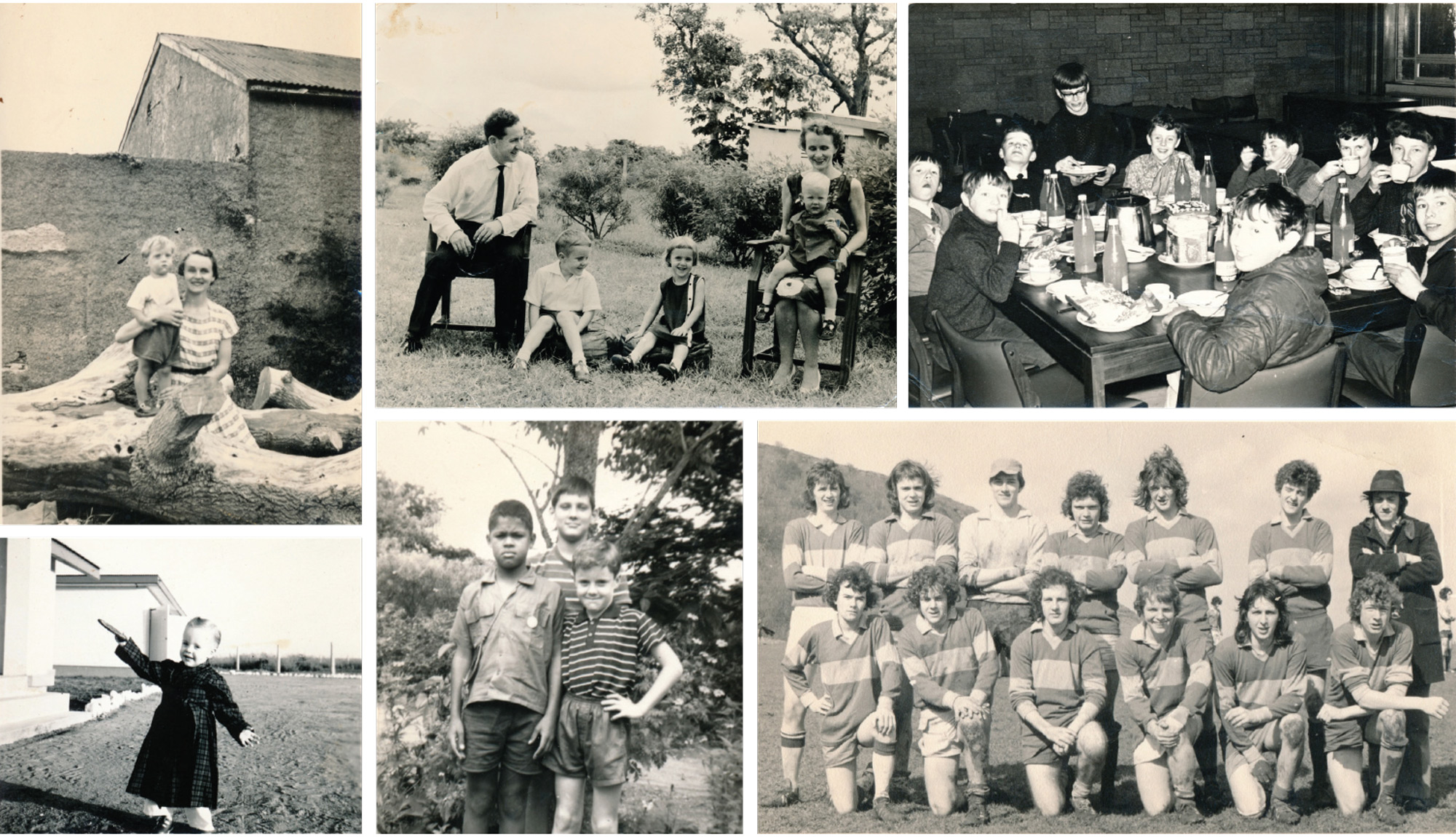

The question of where O’Leary comes from is complicated. Born in 1958 in Ireland’s County Cork to Donal O’Leary, Sr., a scientist, and Margery O’Mahony O’Leary, a civil servant, he moved with his family to Nigeria at just 13 months old. Donal later worked for the U.N. as a geochemist, overseeing the construction of laboratories. At the start of the Nigerian Civil War, the family, including siblings Mary, Raymond, Lynda, and Donal, Jr., returned to Ireland, this time settling in the North. There, they faced another conflict born from ethnic tension: The Troubles.

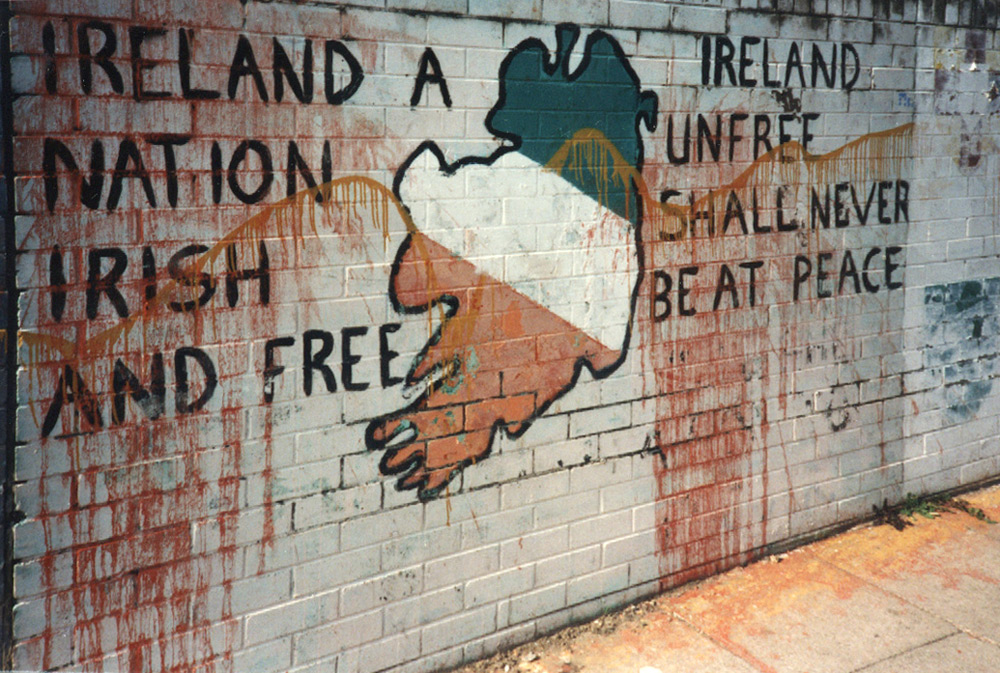

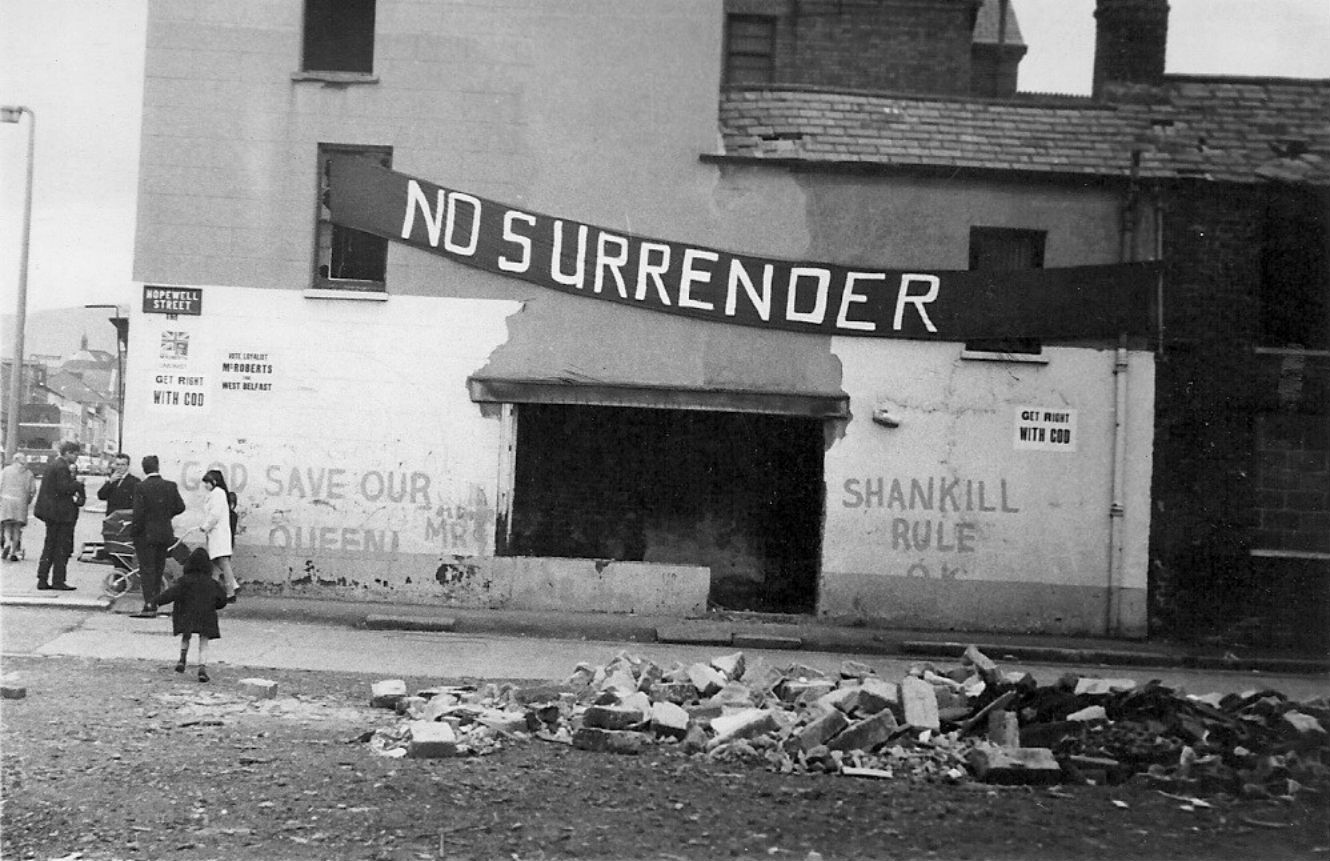

The Troubles, often misunderstood as a religious clash between the local Protestant majority and the Catholic minority, was fought between British military and police forces and republican and loyalist militias, each claiming to fight for the rights of their communities. Civilians bore the brunt of the violence for decades. Coding the conflict as religious is convenient for some, O’Leary argues, because it masks the history of British imperialism in Ireland. Nonetheless, the divide between Catholics and Protestants was stark.

“When I arrived in Northern Ireland, I was an outsider,” he remembers. “You can either be welcomed or treated in a hostile way, and I was treated in a hostile way by both main communities, for different reasons.”

Everything about O’Leary gave off conflicting ethnic tells. For one thing, the influence of his Cork-born parents and his time in Nigeria made his accent hard to place in his new home in the North. For another, his name identified him as Catholic, but he and his sister attended a school otherwise exclusively populated by Protestants. People could not place him.

The study of conflicts shaped O’Leary’s life and career in ways he can only guess at. “Would I have applied to Oxford if it had not been for the conflict?” he wonders. “It’s an interesting question. I did not want to be in Belfast in the middle of that intensity. My decision to go to Oxford meant that I knew my career would likely be outside of Ireland.”

O’Leary’s career has indeed been largely outside of Ireland: school at Keble College, Oxford University, and professorships at the London School of Economics and Penn, as well as roles as a political and constitutional advisor to the U.N., the EU, the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq, the Governments of the U.K. and Ireland, and the British Labour Party. His wife, Lori Salem, is American, and his daughters, Anna, Hana, ENG’20, and Leila, C’20, are respectively English, American, and American. But Ireland has remained the driving force in his work.

History, Down to a Science

O’Leary’s treatise on Northern Ireland was a massive undertaking. So massive, in fact, that he wouldn’t have taken on the challenge of covering five centuries of history, had it not happened organically. What began as a revision of his 1993 book, The Politics of Antagonism, fused with a separate book project on the Good Friday Agreement, the formal end to The Troubles. The result is A Treatise on Northern Ireland, a collection of three volumes, each organized around a theoretical concept: colonialism, control, and consociation, the third being a form of power-sharing.

I respect historical conventions. But I think I have a valuable contribution to make in showing how the historiography fits in relation to theoretical concepts, and I organize the historical material around them quite explicitly.

“I respect historical conventions,” he says. “But I think I have a valuable contribution to make in showing how the historiography fits in relation to these three concepts, and I organize the historical material around them quite explicitly. I’m not making any epistemological error or committing some methodological crime in doing so, though there might be historians who disagree,” he admits.

The first and longest volume of the Treatise covers the long reach of colonialism. Its non-linear organization demonstrates O’Leary’s concept-driven approach. Beginning with a chapter titled “An Audit of Violence after 1966,” it brings readers to the present day. Two chapters later, O’Leary expounds on the far-reaching implications of the 1603 surrender of Aodh Mór Ó Néill, an Irish earl who led an ill-fated rebellion.

“That’s deliberate,” he says. “That’s being a social scientist.”

“What I’m doing is reminding the readers of the intensity of the conflict in Western Europe at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st centuries. I outline that in considerable statistical and political and moral depth. I have to explain precisely what happened, then the rest of the three volumes are a response to that—why did it happen?”

The second and third volumes address the “what” and “why.” O’Leary details the powers that have influenced Northern Ireland since its formation in 1920, arguing that control of Northern Ireland’s Catholic majority depended on a formal system of segmentation (isolating and fragmenting the population), dependence (economic and social vulnerability), and co-option (incorporating some elite members of the otherwise vulnerable population). Here, O’Leary’s work draws on arguments developed by a colleague in the Department of Political Science: Ian Lustick, Bess W. Heyman Professor and expert in Middle Eastern politics.

Lastly, the third volume addresses how relative peace came to Northern Ireland through a consociational approach involving executive, legislative, and judicial power-sharing across Catholic, republican and Protestant, loyalist communities. In the North, these communities were not always recognized by their opponents. Members of the Ulster Unionist Party and Sinn Féin had opposing agendas, the former refused to speak with representatives of the latter. Rather than declaring a victor to take the spoils, consociation results from negotiated bargaining.

Organizing Northern Ireland’s history around these concepts took considerable homework and revision over a roughly 12-year period. O’Leary read prodigiously, conducted interviews, and did archival research. He estimates that about half of what he writes gets deleted as he edits himself.

“I have to test my interpretations; I have to see where they might be wrong,” he says. “How will people object? At each stage, I am constantly interrogating myself.”

Given the contentious nature of Northern Ireland’s history, he’s aware that even the terms he uses are up for debate.

Each of his three volumes begins with a lengthy glossary and preface on terminology. He takes care to define the part of Ireland he’s writing about: Northern Ireland, not the “Six Counties” or “Ulster,” as preferred by republicans and loyalists, respectively.

“I regard it as partly an exercise in intellectual integrity, and partly as a way of helping the reader into matters,” O’Leary explains. “Definitional and interpretive matters frequently intersect, so it’s very important at the outset of the Treatise that I explain how I’m going to use terms. Some people in Northern Ireland will think that they know everything about what’s going to follow simply on the basis of how I define things. That doesn’t concern me.”

O’Leary’s authorial confidence and matter-of-fact acknowledgment of potential detractors are the results of decades of research, writing, and experience. “In a certain sense it’s an older man’s book,” he says. “I don’t have to write to get tenure, I don’t have to conform to every professional norm.”

Though his book is intellectually rigorous and indefatigably researched and referenced, O’Leary most notably deviates from the norm with a playful approach to language. “Love of Latin has melted like the snows of yesteryear,” he laments. “Try saying ‘archipelagic’ with any variety of Ulster accent,” he jokes. Remembering a Victorian historian from a high school reading assignment, he writes, “I found him nauseating.” In his acknowledgments, O’Leary references an old academic dispute, saying, “Having once been described by the late Keith Jeffery as part of a team of academic carnivores, perhaps I need to declare that scholars are not fit for consumption, raw or cooked, though they often make for good reading.”

“All answers to the question of why the Irish are known for their writing tend to be flattering to the Irish themselves, so I’m going to be guilty of that,” he admits. “But the presence of idioms and rhythms from Irish—Gaelige—went into how the Irish speak English. We write in the English language with a sense of our own distinct cultural difference, even if it’s the narcissism of minor differences, and maybe we want to show the English that we can perform in their language better than they can.”

Portrait of the Scholar

O’Leary’s career has been a mix of steady progression and surprising zigzags. After earning an undergraduate degree in philosophy, politics, and economics from Oxford, he went on to a doctorate in political science from the London School of Economics (LSE), where he received an academic appointment in 1983, at age 25.

Early in his career at LSE, he received a letter that sparked a reunion and decades-long writing partnership.

“I was sent an article, through snail mail in those days,” he remembers. It was accompanied by a note from the author, John McGarry, saying that their views were similar. O’Leary recalled a high school classmate with the same name, but that John had been more interested in boxing than academic pursuits.

“I wrote back to him saying, ‘Dear John, remarkably similar, you’re absolutely right. We are very convergent. You couldn’t possibly be the John McGarry I went to school with. You have the same name as him. You’re different, you must be a different character. Where do you come from?’”

The reply came back:

“Dear Brendan, I can understand why you might think I’m not that John McGarry, but I am that John McGarry.”

Once reconnected, O’Leary and McGarry, by then a professor at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, and, like his former classmate, a scholar of power-sharing in contested areas, began to write together. They have co-written or co-edited 10 books together, published journal and newspaper articles, and presented at conferences.

“We developed a long-lasting friendship,” O’Leary says. “Perhaps it was easy for us to work together, because we had a similar formation and were at opposite sides of the Atlantic at that stage. It’s been incredibly fruitful, I hope for both of us.”

O’Leary and McGarry, though living outside of Ireland, were deeply involved in the processes of peacemaking and reform that dominated the political landscape of Ireland, Northern Ireland, and Britain in the ’90s.

The Good Friday Agreement of 1998, the formal end to The Troubles, was a complex political achievement. In the run up, O’Leary was an advisor to Britain’s Labour Party, which, at the time, was led by Prime Minister Tony Blair.

Negotiated between the British and Irish governments and eight political parties from Northern Ireland, the Agreement’s articles addressed a sweeping number of issues, including the establishment of cross-border political and cultural institutions, the decommissioning of weapons held by paramilitary groups, and the right of people from Northern Ireland to identify, be accepted, and hold citizenship as Irish, British, or both. Police reform was identified as integral to peace, though what that might look like remained unknown.

In the years following the Agreement, O’Leary became a prominent voice in academic and popular discussions of police reform in Northern Ireland. In 1999, he and McGarry published Policing Northern Ireland: Proposals for a New Start. Many of their recommendations, including renaming the police force and recruiting more Catholic and female officers, were taken up by the Independent Commission on Policing. The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) launched in 2001 and, by 2007, was officially endorsed by all of Northern Ireland’s political parties.

The Agreement and reform that followed are largely considered successful peace negotiations and strong examples of consociation, the form of power-sharing O’Leary details in the third volume of his Treatise. Since 1998, Northern Ireland has remained ethnically and religiously divided, but until 2016 had maintained stable democratic rule without returning to the sustained violence of The Troubles.

In 2001, as the PSNI launched, O’Leary came to Penn as a visiting professor. Recalling his visit, he says that Penn “made an offer I couldn’t refuse,” and he joined the faculty the next year. Early in his tenure in the Department of Political Science, he received another message that changed the direction of his career.

I gave the talk, and afterwards the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister of the Kurdistan region asked me, would I be willing to advise them if the Americans removed Saddam from power?

The email came from Khaled Salih, an academic whom O’Leary had exchanged a few emails with in the early ’90s. Salih asked him to visit the University of Southern Denmark and give a lecture on 10 years of Iraqi Kurdistan. When O’Leary pointed out that he was not an expert in Kurdish or Iraqi politics, Salih encouraged him to apply knowledge about power-sharing in Northern Ireland to this new context. Intrigued, O’Leary agreed to the trip.

“I gave the talk, and afterwards the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister of the Kurdistan region asked me, would I be willing to advise them if the Americans removed Saddam from power?” O’Leary remembers. “I said ‘yes,’ assuming that the Americans were not going to remove Saddam! With the support of Penn, I was in Kurdistan for most of the first half of 2004, and again for a lengthy period in 2005. This was during the making of the transitional administrative law and then the making of Iraq’s constitution. These were some of the most remarkably interesting experiences of my life.”

O’Leary’s work in Kurdistan led to his being part of the U.N. Standby Team, a group he jokingly refers to as the A-Team, with experienced negotiators, conflict specialists and mediators from around the world. As part of this group, he was an advisor in the Darfur peace process and a participant in talks that preceded the breakup of Sudan.

Reflecting on working with the U.N., the same organization for which his father worked in his childhood, O’Leary remembers a joke his father told him: “Brendan, there are three great lies: The check is in the post, My wife doesn’t understand me, and I’m from the United Nations and I’m here to help you.”

“I tried in my own way when working for the U.N. to make that last joke untrue. But I would argue that people like me, whether lawyers, political scientists, or human rights specialists, are more useful in working for governments or working for rebel parties or dissidents in negotiations. All such work is important, because it’s easier to have good bridges and good hospitals if you have decent government.”

Don’t Call It Brexit

The 2016 U.K. EU membership referendum got O’Leary up in the middle of the night, and he’s been thinking about it ever since.

“I went to bed on the 23rd of June thinking that the outcome was going to be 52–48 to stay,” he remembers. “I was in Cushendall, Northern Ireland and I got up at four in the morning and saw that the result had gone the other way. I couldn’t get back to sleep. I was scheduled to speak at a public seminar on the referendum at Queen’s University Belfast, and my mind was already applying power-sharing logics. By the following day, I was writing an op-ed on how Scotland and Northern Ireland could remain in the EU for the United Kingdom while England and Wales left.”

O’Leary has continued writing and speaking about the results of the referendum and potential power-sharing compromises that may ease matters, appearing on NPR and RadioWharton, as well as in The Irish Times, Guardian, and HuffPost. One of his main talking points? Under the terms of the referendum, it’s not just Britain that would be exiting the EU.

“I insist on calling it ‘UKexit,” he says. “Which, fittingly, sounds like a vomit projectile. I insist on it for a good reason. Britain is not the same as the United Kingdom.”

The U.K. is made up of England, Scotland, and Wales, all on the island of Britain, and Northern Ireland. Though 62 percent of Scottish voters and 55.8 percent of Northern Irish voters voted to remain part of the EU, the overall vote determined the path for the U.K. as a whole. A majority of English and Welsh voters chose to leave the EU (53.4 percent and 52.5 percent, respectively). “So,” O’Leary explains, “English politicians insist, Northern Ireland and Scotland must leave, too.”

O’Leary compares the referendum, unfavorably, to the Good Friday Agreement. In his view, voters across the U.K. were not properly educated about what leaving the EU would mean.

He explains, “The Good Friday Agreement went to referendum in Northern Ireland and in the Republic of Ireland. Every household in the North got a 30-page booklet full of institutional detail, explaining what would happen if they endorsed the agreement.”

With the referendum on “UKexit,” voters were faced with many unknowns.

O’Leary lists some of the unanswered questions: “Would they leave the single market? Would they leave the customs union? Would they leave what are called the flanking policies, e.g. fishing? Would they continue to have police and intelligence cooperation? Would there be some special travel arrangements?”

These answers matter for the continued success of the Good Friday Agreement, which is built on the cross-border cooperation that membership in the EU allows.

The third volume of the Treatise addresses UKexit. In its preface, O’Leary writes that UKexit has unintentionally set the stage for future referendums, ones that he hopes will be better designed and better understood by voters.

A united Ireland hasn’t been defined. If it comes to a vote, I hope to contribute to clarifying the terms of any possible Irish reunification.

He predicts that there will be another vote on Scottish independence—the 2014 referendum resulted in 55.3 percent of voters choosing to remain part of the U.K. And then there are other possibilities, ones that before UKexit seemed unlikely: a vote for Northern Ireland to leave the U.K. and reunify with Ireland, and a subsequent matching vote in the Republic of Ireland to endorse reunification.

If there were a vote on reunification, it would need to be as carefully negotiated and communicated as the Good Friday Agreement.

“A united Ireland hasn’t been defined,” O’Leary says. “If it comes to a vote, I hope to contribute to clarifying the terms of any possible Irish reunification.”

•••

Brendan O’Leary has lived more of his life outside of Ireland than in it. A citizen of the U.S., Ireland, and the EU, he has a visiting professorship at Queen’s University Belfast and what he calls a “social summer home” in Northern Ireland: the village of Cushendall, in Country Antrim. His brother and sister-in-law live there and it’s three miles from St. MacNissi’s College, Garron Tower, the boarding school where he met John McGarry years before their academic partnership began.

“It’s a beautiful village,” he says. “I try to get there every summer. Every morning, as long as there’s no clouds or rain, I see Scotland across the Sea of Moyle.”

A lot has changed since his high school days, and those changes are what make the possibility of a re-unified Ireland all the more interesting. The Troubles have ended and the North has become a tourist destination, bolstered by the draw of natural attractions like Giant’s Causeway and cultural sites like filming locations for Game of Thrones and the Belfast shipyard where the Titanic was built. The Republic has seen the boom and bust of the Celtic Tiger economy, followed by Dublin’s emergence as a tech hub—“in which computers and chemicals are more important than cows,” O’Leary comments. The social influence of the Catholic Church has loosened, with Ireland becoming the first country to legalize same-sex marriage by popular vote.

But challenges remain. “The Republic of Ireland is now a rich country, a land of immigration,” says O’Leary. “People want to go live there. It is a fabulous thing to see.” The North, on the other hand, is still partly a land of emigration, particularly of the college-educated, echoing O’Leary’s own choice to learn and work elsewhere. The status of the Irish language is an illustrative example of the cultural and political gulf between the North and the Republic: In the Republic, Irish is the national language and English has full official status. Irish appears on all street signs and is taught to all school children. In the North, the Good Friday Agreement requires “respect, understanding, and tolerance” of the Irish language, along with English and Ulster Scots, but that provision has not yet been translated into the substantial recognition of Irish. Legislation that would require bilingual signs or the appointment of an Irish language commissioner has been met with political resistance. To imagine a Northern Ireland that is reunified with the Republic, one must first address all the policies that separate the two places.

“Changes are perhaps more visible to me than to someone who has lived through them all,” O’Leary says. “I haven’t added up all the time I’ve spent in Ireland, but I don’t think a single year has passed in my adult life where I haven’t spent some time there. I get to be in the places I regard as beautiful or poignant, and I’m able to transmit knowledge and learn in many places. I’ve never felt exiled.”

Armed Conflict

The latest round of armed conflict in Northern Ireland—O’Leary rejects the commonly used name, The Troubles, as euphemistic—began in 1966. But, it had roots earlier in the 20th century, when rebellion and war concluded in the British partition of the island of Ireland into two distinct entities: Ireland (also known as the Republic) and Northern Ireland. Combatants in the conflict ostensibly represented the predominantly Catholic Irish nationalists or republicans, who wanted the North to reunify with Ireland as a single, sovereign nation, and the predominantly Protestant British unionists or loyalists, who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom, along with England, Scotland, and Wales.

- ~50,000 seriously injured between 1968 and 2011

- ~4,000 deaths

- 2/3 of the dead were civilians

- 1/2 were killed in Belfast

Say Nothing

The poet Seamus Heaney titled a popular poem: "Whatever You Say, Say Nothing." It was a warning akin to U.S. wartime slogan “Loose Lips Sink Ships.” But in Northern Ireland, the phrase informed daily civilian life. In times of conflict, O’Leary’s Treatise and Heaney’s poem explain, your name, your address, and your school can give away who you are. Better in that case to remain silent, practicing what Heaney calls, “the famous / Northern reticence, the tight gag of place / And times.” O’Leary’s open approach to scholarship on Northern Ireland, which weaves in his background, is a rebuke to the culture of silence enforced by The Troubles.