The Wallace Tales

David Wallace’s life has been guided by his love of medieval literature and his certainty that it has much to say to today’s world. But he finds time for a day at the races, too.

Prologue

went to Worcester Cathedral, and then to the horse races in the afternoon. I placed one bet. It was on a horse called Byzantine Empire, and it won at 8 to 1.”

It seems like a typical summer day for David Wallace, Judith Rodin Professor of English, whose interests range far beyond the medieval literature on which he is a renowned expert. An hour-long conversation with him touches on cathedrals and horses, on Geoffrey Chaucer, the Enigma code breakers, steam trains, free-range parenting, Marxism and Catholicism in East Germany, the climate crisis, the Olympics, Longfellow, the British royal family, and the new British PM.

Suggest that he’s a Renaissance man and Wallace laughs. “No, I’m not a Renaissance man, I’m a medieval man. It’s because I’m well-informed by all my contributors. I look for a hundred smart people to tell me the things I need to know, and then I seem smarter than I really am.”

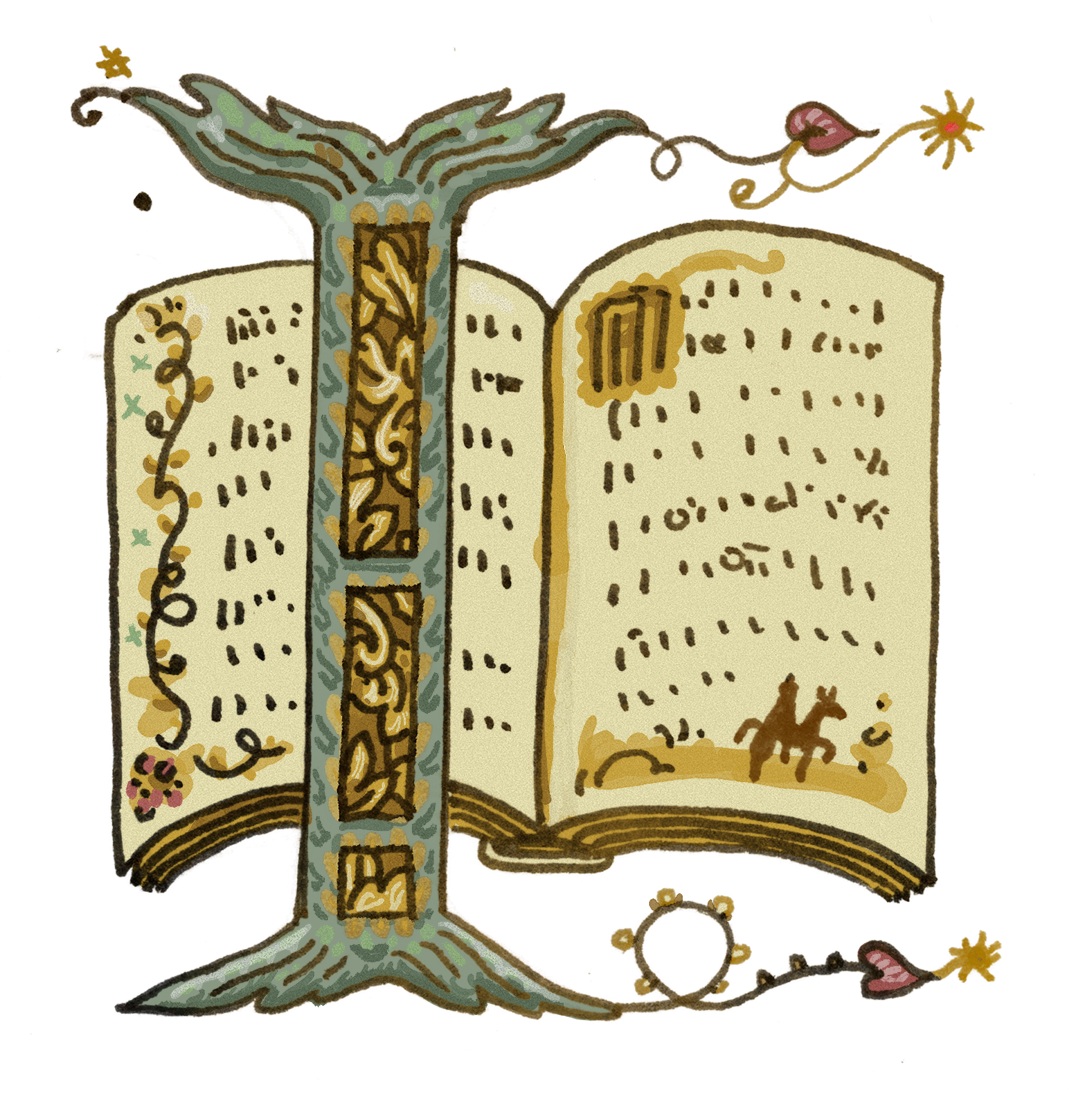

Wallace is being modest, but he really is working with 100 smart people (and counting) on his latest project, a book and website on national epics. It’s the most recent chapter in a tale that spans decades and genres, encompassing 10 books, multiple teaching awards, and a move to the U.S. to be with his future wife. He has traveled to learn more about the medieval literature that is his life’s work, the world in which he lives, and how the two connect. Like Chaucer—Wallace’s first literary love and his scholarly focus for decades—he is authoring a story that interweaves duty and delight.

I’m not a Renaissance man, I’m a medieval man. It’s because I’m well-informed by all my contributors. I look for a hundred smart people to tell me the things I need to know, and then I seem smarter than I really am.

“It’s been a tremendous privilege, about as good of a life as I could have ever had,” he says. “I’m simply grateful for the teaching and the students and the colleagues and everything else.”

Chapter One: The Scholar

Though “creaking joints” have caused Wallace to give up soccer for biking, his academic journey has not slowed. He’s organizing his 100 contributors as they explore national epics in countries around the world. It’s an effort to comprehend the cultural mechanics and resurgent appeal of nationalism on a global scale.

For each nation, an author determines its representative epic, then examines when that choice was made and how well it’s holding up. “The myths we live by, the stories we tell, that’s the fascination of the project,” says Wallace. The website, designed by Penn’s Price Lab for Digital Humanities, is already live, and Oxford University Press will eventually publish the book (in three volumes).

This follows 10 previous books, including Europe: A Literary History 1348–1418 and Geoffrey Chaucer: A New Introduction. Among many accolades, Wallace was named a Guggenheim fellow in 2009, and in 2019 was awarded the Sir Israel Gollancz Prize by the British Academy. Recently, he was honored with a conference known colloquially as “Wallacefest.”

More than 30 of Wallace’s former doctoral students participated in the two-day event (officially called Premodern Literature and Global Histories) organized by Megan Cook, GR’11; Daniel Davies, GR’21; and Emily Steiner, Rose Family Endowed Term Professor of English. Presenter after presenter considered the roles Wallace’s work will play in the future of medieval studies. The event wound up at the house Wallace shares with spouse Rita Copeland, Sheli Z. and Burton X. Rosenberg Professor of Classical Studies, with celebrations stretching into the night.

Chapter Two: The Englishman

Wallace grew up in Bletchley, England, a small factory town at the crossroads of the Oxford-to-Cambridge and London-to-Manchester railway lines. His mother was from a rural family; she joined the Women’s Land Army during World War II and enjoyed it so much she stayed in until 1950. A royalist (unlike her son), she twice met Queen Elizabeth II. His engineer father served as a Royal Air Force pilot in the war.

When he was young, Wallace loved steam trains and explored much of the geography of England via train, his father dropping him off at one station and picking him up at another. He also loved reading and by 16 was downing the complete works of Milton. “For me, it was a form of rock-and-roll rebellion, because nobody else was doing that,” he says.

His first encounter with Chaucer was not auspicious. “The teacher had never taught Chaucer before and was piecing it out bit by bit,” Wallace says. When he got to York University, most of his fellow literature students were focusing on the 20th century, but Wallace heard a medieval studies professor there read Chaucer aloud and fell under the poet’s influence. “It was so expressive and powerful,” Wallace remembers.

He still cares deeply about “the voicing” of Chaucer’s work, partnering with the audio poetry site PennSound and collaborating on performance pieces. He even has his students learn to read the text aloud.

“Fourteenth-century English hadn’t yet stabilized,” says Wallace. “Chaucer had the opportunity to write from the beginning.”

Chapter Three: The Traveler

Like Chaucer, Wallace’s life and work have been shaped by travel. At college, he learned Italian, now the language he loves best and feels most comfortable with. Time in Italy opened his world as it had for Chaucer. “His trips to continental Europe led to his discovery of great contemporary writing in France and especially Italy—authors like Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch,” explains Wallace. “He was inspired to think that the humble English language, too, might achieve great things.”

After graduating, Wallace spent a year at Leipzig University, and toured Eastern Europe, publishing his first article about his experience in communist East Germany. After another year in Italy and a summer working with intellectually disabled adults in England, he began his doctoral studies at St. Edmund’s College, Cambridge. There he met an American graduate student named Rita Copeland. “It was like animal magnetism in a medieval classroom,” he says. “I always tell my graduate students never to get involved with a fellow student, but I didn’t take my own advice.” The day after he turned in his thesis, he headed to the United States (where Copeland was finishing hers). More moves followed for the pair, to Stanford, the University of Texas, the University of Minnesota, and finally to Penn.

Wallace is grateful to be working in both the U.S. and U.K. “The United States is really good at developing your ability to think abstractly, philosophically, paradigmatically,” he says. “The English side is much more pragmatic: content, history, manuscripts, archives.” His new nation has failed him in at least one way, however: The former sweeper never found a place to play soccer in Philadelphia, though he remains a lifelong Manchester United fan.

Chapter Four: The Teacher

In 2024, Wallace won the Lindback Award for Distinguished Teaching, the University’s highest teaching honor. “When I announced that he won, a colleague said to me, ‘Everything about David is distinguished,’” says Department of English Chair Margo Natalie Crawford, Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Professor for Faculty Excellence. Wallace had previously received the Ira Abrams Award for Distinguished Teaching, the top School of Arts & Sciences award, and been honored twice by the English Undergraduate Advisory Board.

One secret to being a good teacher, he says, is to really like the kids: “If they know, or suspect, you’d rather be somewhere else, you won’t succeed.”

Wallace believes it is crucial for English faculty to teach writing. He edits all of his students’ papers and calls the seminar model “an alternative to AI in collective learning. That’s a key task, to help each student develop a style that is like their fingerprint as a writer.”

Given his specialty, Wallace has another challenge: teaching students accustomed to the quick-digest nature of social media about an alien medieval world in what is almost another language. Reading 300 pages of anything, he adds, has fallen out of fashion. “We’re trying to create an environment where you can think a little longer,” he says.

To that end, Wallace has taught multiple classes on medieval women writers, and on Dante, whom he says “just blows everyone away. The Divine Comedy is a deeply beautiful poem. A complete poem.” His class this fall, After Dante, looks at the way the poet inspired writers from T.S. Eliot to Bob Dylan to Lil Nas X.

He keeps the atmosphere relaxed but rigorous, and he’s supportive even as he’s pushing you in the right direction. Alongside this great scholarly and teaching perspective, he’s funny and down to Earth.

“These classes are a breath of fresh air,” says Daphne Glatter, C’25, who has taken two with Wallace. “He keeps the atmosphere relaxed but rigorous, and he’s supportive even as he’s pushing you in the right direction. Alongside this great scholarly and teaching perspective, he’s funny and down to Earth.”

Wallace teaching the class Travel Writing: Preparing for Your Journey, one of more than four dozen courses he has taught since arriving at Penn in 1996.

Chapter Five: The Globalist

It may be surprising given his scholarship, but Wallace is motivated by current events. “Just like everyone, I’m thinking, ‘Why are things happening the way they are?’” In 2022, as his national epics course was discussing Russia, Russia invaded Ukraine. “The present is breaking into the classroom all the time,” he says.

It did so dramatically just after Wallace published Europe: A Literary History 1348–1418, “two big, fat volumes” that traced linguistic paths through Europe and beyond after the bubonic plague. He and 85 contributors spent seven years studying how literature followed routes taken by merchants, pilgrims, armies, and disease, looking beyond categories like “English literature” or “Italian literature.” It published in 2016—two weeks before Brexit, in which the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union.

“I thought I’d given birth to the biggest white elephant because I was very much hoping this would help integrate Britain into Europe, to show how we’re part of a connected culture,” he says. “But politically, what’s happening is a hardening of nationalism.” The national epics project, which will eventually run “from Albania and Algeria to Vietnam and Wales,” is his response.

Wallace is also informed by his National Epics class, which he is teaching this spring for the sixth time. He looks to students with knowledge of a particular locale or its diaspora as his “expert informants.” “The students realize that their own family histories are wrapped around these sagas of nations,” he says. “Your family has lived out its own rich and complex history, but then the state adopts certain limited views of nationhood and institutionalizes them. Inevitably some people get left out or misrepresented.”

It’s never simple, he concludes, “but the class is a trusting, supportive place to think these things through together.”

Epilogue: The Continuing Tales

Wallace’s journey continues. His greatest concern now, he says, is “that we do not fry our planet to death.” He collaborates with the Faculty Environmental Humanities Working Group, as well as the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program, Italian Studies, the Program in Comparative Literature and Literary Theory, and Kelly Writers House. He’ll shortly publish a chapter on Dantes in America, with special emphasis on African American Dantes, and another on Walt Whitman’s personal copy of Dante’s Inferno. (He’s also the campus go-to on the British royal family—despite never having met Queen Elizabeth himself.)

“He cares deeply about the past, present, and future of Penn English,” Crawford says. “David is an award-winning teacher and a dedicated mentor to undergraduate and graduate students, and he’s an incredibly prolific scholar.”

Decades in, Wallace himself is still learning, about national epics, about Chaucer and other writers, about the world, and teaching others to dive in with him. “It’s tremendous fun,” he says.