On the Rise

In his new book, Wale Adebanwi, Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Africana Studies and director of the Center for Africana Studies, explores social mobility, ethnonationalism, and democratic politics in Nigeria.

To hear Wale Adebanwi describe his time as a young journalist in a destabilized Nigeria is like something out of a movie: a young reporter fleeing to the underground to avoid reprisals and jail time from ruthless military rule.

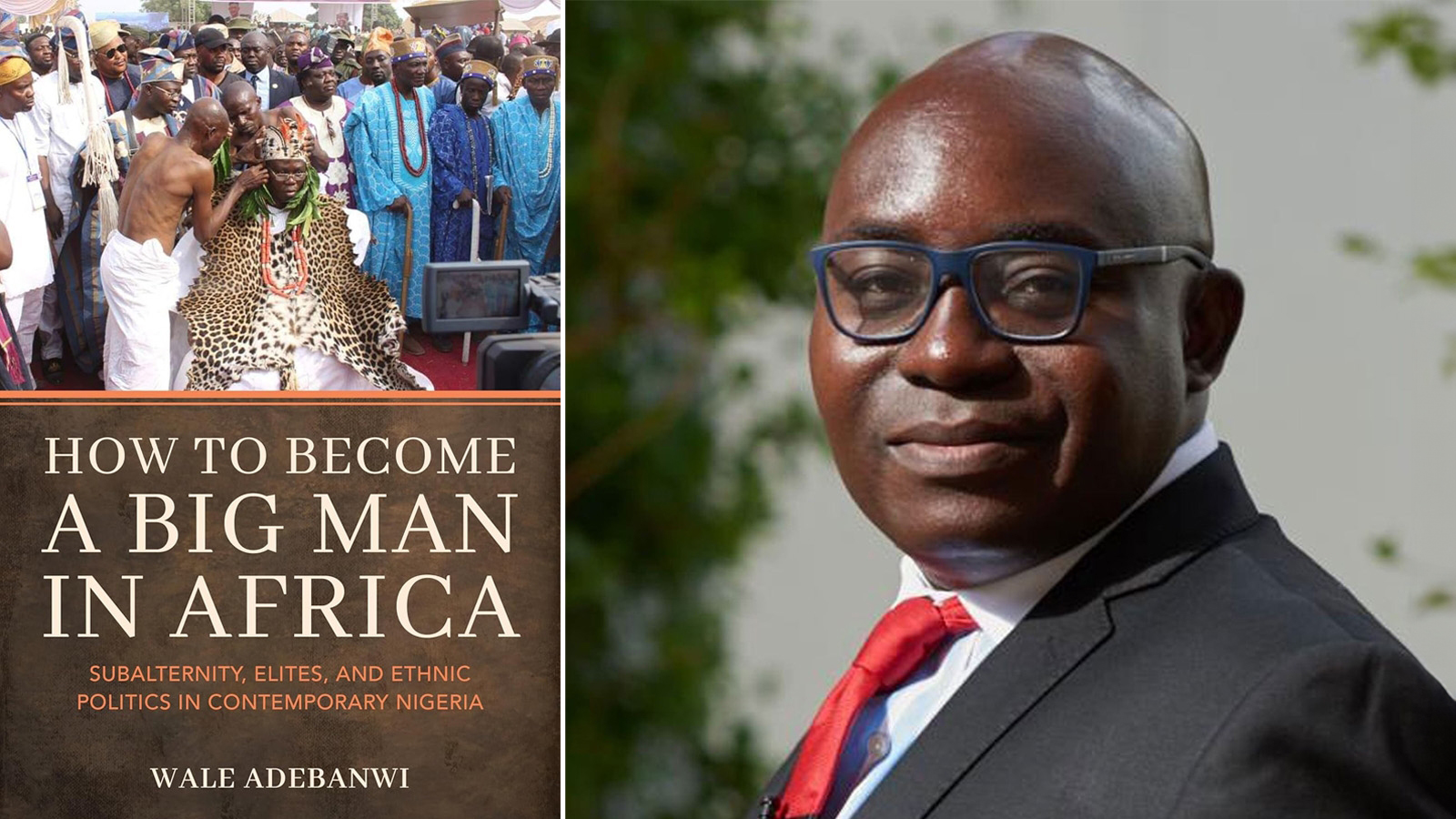

Wale Adebanwi, Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Africana Studies and Director, Center for Africana Studies (Image: Courtesy Wale Adebanwi)

“It was both terrific and terrifying,” says Adebanwi, Presidential Penn Compact Professor of Africana Studies and director of the Center for Africana Studies. “Some members of my generation of journalists and activists were killed, some went to jail, but it was like the duty of our generation to be the foot soldiers for the democratic struggle in Nigeria. It was useful in terms of understanding social dynamics, and I think it has contributed a lot to the kind of intellectual enterprise that my generation has been engaging in since the end of that era.”

Adebanwi’s new book sees him resurrecting the journalistic roots he lived by decades prior. How to Become a Big Man in Africa: Subalternity, Elites, and Ethnic Politics in Contemporary Nigeria delves into youth, violence, and social dynamics against the backdrop of seismic governmental evolution.

Adebanwi focuses specifically on the larger-than-life Gani Adams, who transformed himself from a “subaltern” of lower status into the holder of the most prestigious chieftaincy title among southwestern Nigeria’s Yoruba, a culture represented through diaspora in locations from Brazil to the Caribbean. The book is composed of observations made over decades of Adams’ social and political trajectory—a path that came to mirror deeper themes of tradition versus modernity in Nigeria.

“The southwestern and southern parts of Nigeria generally had the earliest encounter with ideas about the Enlightenment, and by the mid- to late-19th century, the role of reason and ideas about human liberty had been embraced prior to the formal imposition of colonialism,” says Adebanwi.

One of the keys to advancing in modern Nigeria is education, says Adebanwi, who received a degree in mass communication before completing two master’s and two PhDs—one in political science and one in social anthropology. The irony of a well-educated scholar writing a book about social mobility was not lost on Adebanwi. “As I argue in the book, I could also qualify as a member of the elite, because one of the most important ways of social transformation in that part of Nigeria was education.”

During his time as a journalist, Adebanwi had gained access to the Oodua People’s Congress (OPC)—a faction of which was led by Adams—an ethno-nationalist organization that had violent clashes with other groups. As tensions flared, Adams, then 29, was declared a wanted man. “He was underground being sought by the police and then eventually arrested, put to trial, and released,” Adebanwi. “I met him at that point, in the early 2000s.”

Adebanwi focuses specifically on the larger-than-life Gani Adams, who transformed himself from a “subaltern” of lower status into the holder of the most prestigious chieftaincy title among southwestern Nigeria’s Yoruba, a culture represented through diaspora in locations from Brazil to the Caribbean.

The timing was fortuitous. The Social Science Research Council in New York had started an African Youth in a Global Age fellowship, which offered funding for researchers studying youth in the context of socioeconomic and political processes in Africa. Adebanwi was selected and decided to focus on the OPC—the beginning of what would become a decades-long data-gathering process. It eventually gave him a deep and rare insight to write the book.

“I ended up studying Adams and the group as a mirror into Nigerian society. Adams is a model of how somebody who had been dismissed as a ‘vagrant’ or vigilante became somebody of consequence over time,” says Adebanwi. “He was mobilized by the elite as a nationalistic activist figure in the ethno-regional democratic struggle, and he eventually learned to use that to his advantage.”

Adams’ rise was fueled by mobilizing violence and “culture.” Adams, who dropped out of high school in the third year due to poverty, went back to school to get his degree and was eventually awarded an honorary doctorate.

“One of the things I try to capture, against the backdrop of history, is how the Yoruba embraced the idea of modernity in their earlier encounter with missionary Christianity and how Adams, in this context, transformed the old traditional ideas of warlordism into a modern context of democratic aspirations and ethno-nationalist struggle,” says Adebanwi. “The second focus is what it means to be a Yoruba in the modern age: to be educated and to mobilize the idea of ‘progress.’”

When the book came out, Adebanwi sent Adams a message. “I was worried we might have a fight but when he got the copy, he looked at himself on the cover, and he was gushing,” says Adebanwi. That could always change as Adams examines the book more closely, he adds, but it’s a win for the moment.

As far as Adebanwi’s future plans, he hopes to author a series of two more books—to complement the current one and an earlier one, Yoruba Elites and Ethnic Politics in Nigeria—studying the region’s elite as a way to understand the social, cultural, and political trajectory in Nigeria. He’s also exploring the idea of a documentary film on the latest book.