Tree Wisdom

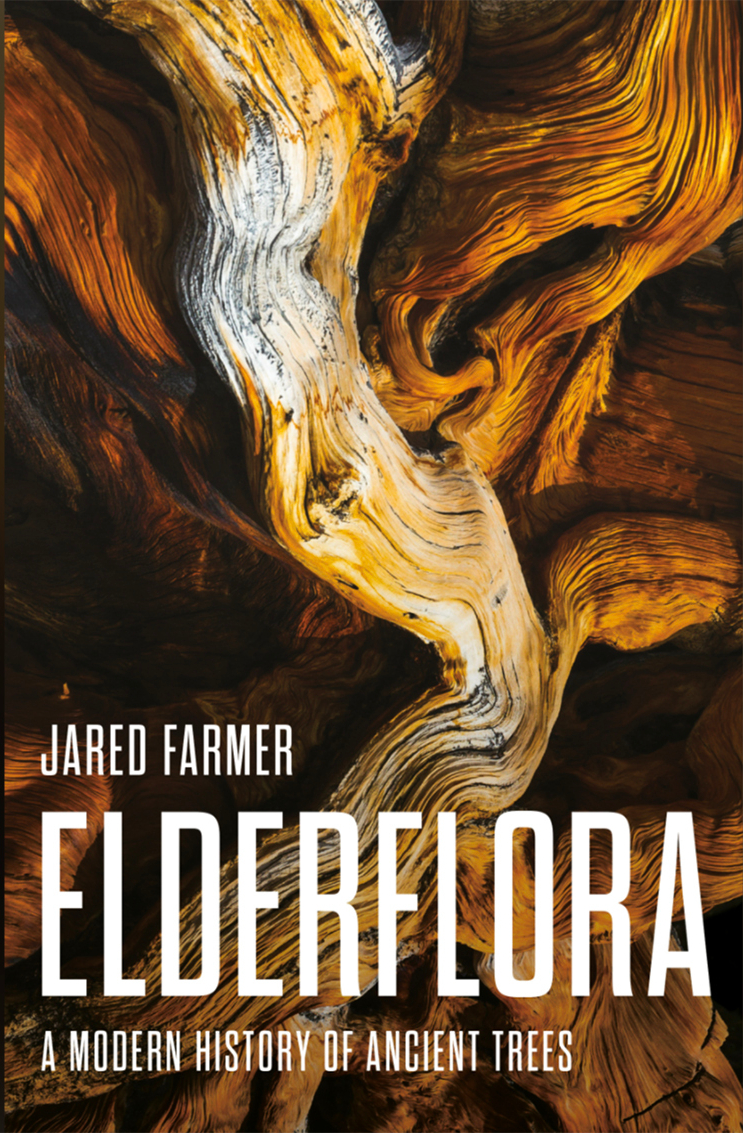

In his new book, Jared Farmer, Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History, examines what trees can teach us about the climate crisis and our relationship with time.

Humans have a long history of venerating ancient trees. That reverence and caretaking took a modern turn in the 18th century, when scientists embarked on a quest to locate and date the oldest living things on Earth, as Jared Farmer, Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History, narrates in Elderflora: A Modern History of Ancient Trees. The book takes readers from Lebanon to New Zealand to California, looking at the complex history of the world’s oldest trees, their relationship to time, and how they can help us address the climate crisis.

Humans are remarkably skilled at looking into our deep history, says Farmer, but they’re not particularly adept at thinking about the long future. Trees, however, are ideal for long-term climate thinking. Trees can persist for thousands of years. Their wood rings store valuable data about past climates, weather events, and natural disasters, and offer insight into events on a planetary to regional to local level that can be tied to calendrical dates and therefore historical chronicles. This makes trees powerful timekeepers, says Farmer.

“Ancient trees are bridges between short time and deep time, between lived human time and abstract geological time,” continues Farmer, whose book looks at 5,000 years of living trees through the lens of science, religion, and history, as well as the long-term relationships between people and individual trees.

Elderflora joins a growing group of arboreal science- and tree-themed books released in the past decade, including the forest ecologist Suzanne Simard’s best-selling memoir, Finding the Mother Tree; the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Overstory by Richard Powers; and Barkskins, by Pulitzer-winner Annie Proulx.

Farmer believes this surging popularity relates to both the human desire for the connection that trees embody through their mycorrhizal network, as well as the increasing urgency surrounding the climate crisis, which has already killed or damaged ancient sequoias, ancient olives, ancient kauris, and other long-lived tree species. He says, “The ‘mother tree’ is a metaphor for connectivity based on mutualism and care. This idea is very attractive in our current moment of miscommunication, disinformation, animosity, distrust, and political breakdown. This notion that there are beings out there who have a wholly different model of sharing and cooperating is inspiring.”

Farmer highlights Indigenous groups and religious figures who serve as caretakers for ancient trees. He also quotes from his conversations with scientists, who agree there’s a “real crisis right now for forests and trees, especially old trees, and most especially big old trees, whose climate of establishment is now long gone.”

Humans have already changed the climate going forward centuries, perhaps millennia, Farmer notes. He hopes that understanding ancient trees and our relationship to them will develop our capacity for hindsight and foresight and create emotive connections to the far future in order to work together on climate now.

“There is much to learn about how to best live on Earth from trees,” he says. “Trees are solar-powered, vegetarian, and committed to their locale. There’s something deeply inspiring and deeply Earth-appropriate about that way of living. There’s no reason to think our species can’t have at least a few million more years in its future, if we learn to live appropriately alongside life-forms that preceded us and will surely outlast us.”

Banner illustration by Nick Matej