Translating a Holocaust Memoir

For his capstone, Andrew Cassel, LPS’20, revealed a new story in this dark history—and learned about his grandfather in the process.

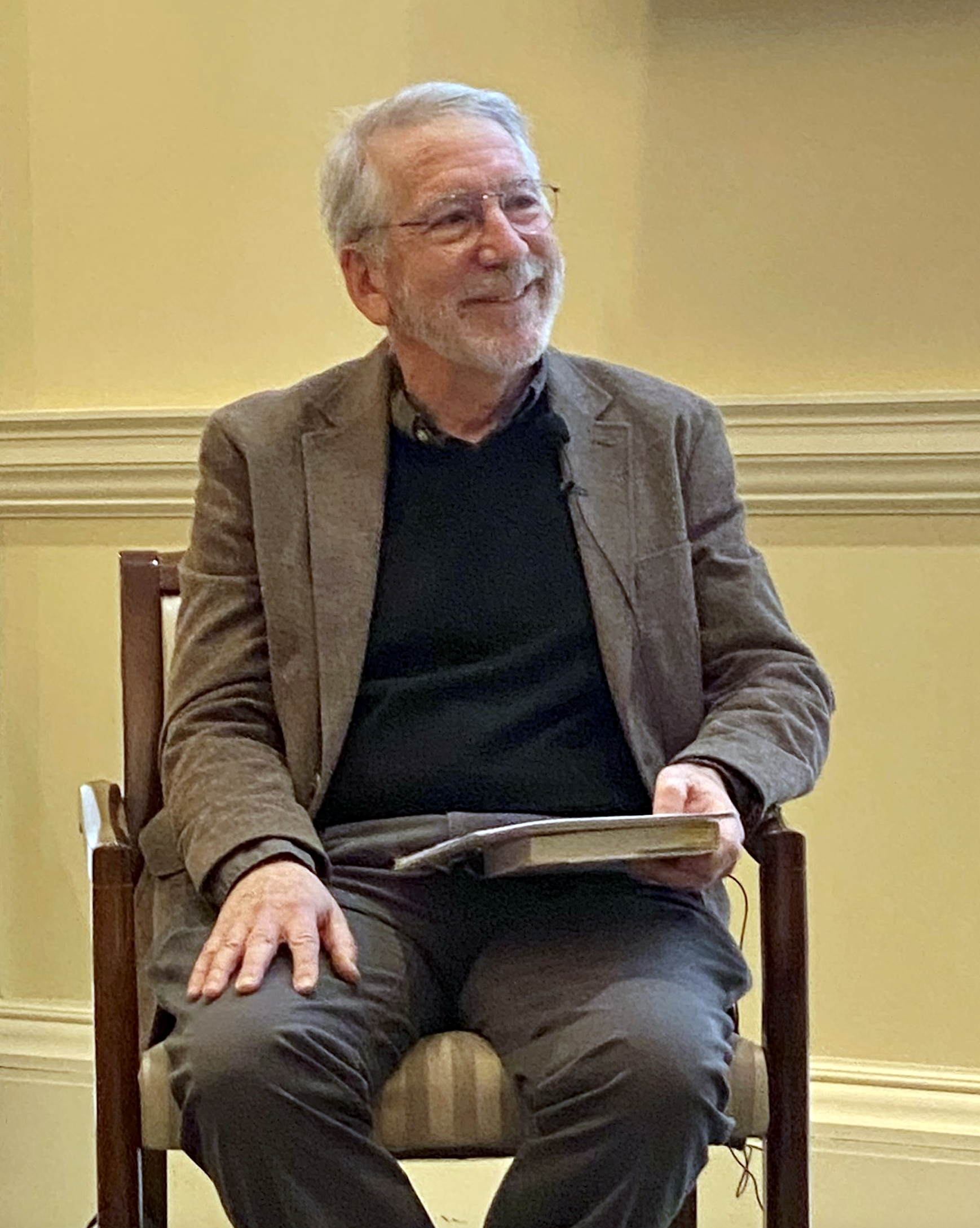

When Andrew Cassel retired after a 35-year career in journalism, the idea of going back to school appealed to him. Little did he know his academic journey would lead to a years-long passion project.

“I was pleased to learn about Penn’s Master of Liberal Arts program,” says Cassel. “Almost everything is open to you. I took classes in history and religion, and I was particularly interested in Jewish studies and anthropology.”

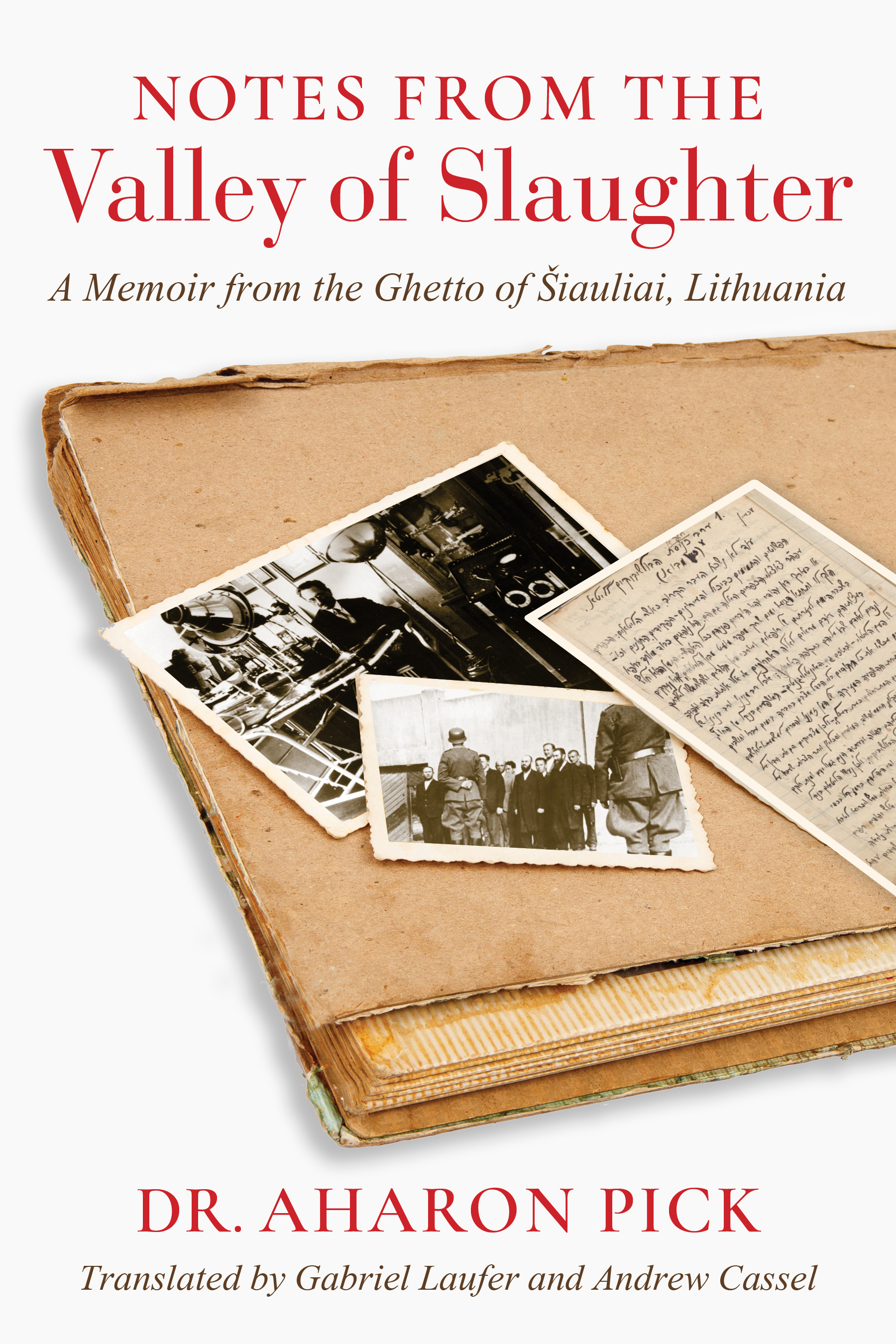

Cassel completed the M.L.A. degree in 2020, and his final assignment resulted in Notes from the Valley of Slaughter: A Memoir from the Ghetto of Šiauliai, Lithuania, a Holocaust memoir written by a Lithuanian physician, Aharon Pick, and translated into English by Cassel and Gabriel Laufer, a retired University of Virginia engineering professor. It published this spring.

Family Roots

For several years, Cassel had been studying and translating Yiddish on his own, primarily to learn more about the life of his Russia-born grandfather, who had written in Yiddish for a small circle of fellow immigrants from the town where he grew up in what is now Lithuania, called Keidan in Yiddish or Kėdainiai in modern Lithuanian. “When I enrolled in the M.L.A. program, I thought I could tell his story and fit it into the wider context between history and anthropology,” Cassel says.

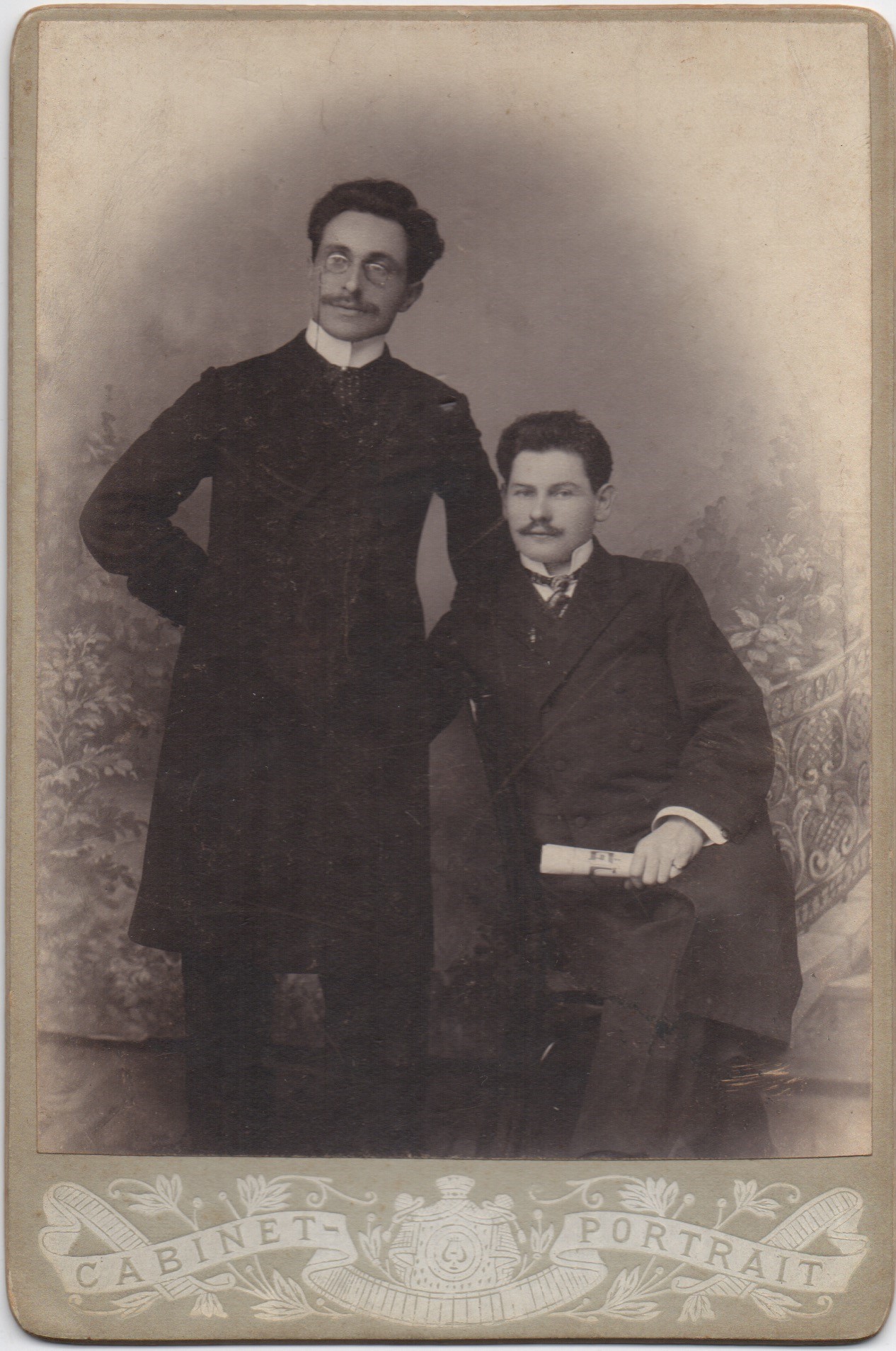

As young men in Keidan, Pick and Cassel’s grandfather, Boruch Chaim Cassel, had been friends. In about 1899, the two got involved in collecting folk music around town, gathering approximately 150 lyrics and submitting them to the Ginsburg and Marek Collection, considered the first published collection of Jewish folk music.

Boruch Cassel emigrated to the United States in 1904, but Pick remained in Europe, studying medicine in Paris. He returned to Lithuania after World War I and spent 16 years working as a doctor in a hospital in Šiauliai. Pick was also a prolific writer.

“He wrote articles about Zionism,” says Cassel. “He wrote about growing up, and he wrote medical papers of various kinds. He apparently wrote a couple of novels, but some of his writings were lost during the war. Toward the end of the 1930s, the situation in Lithuania had grown worse. He ended up being the only Jewish doctor working in the hospital amid a constant pull of antisemitism.”

Pick’s journals cover the tumultuous history of Lithuania from the late 1930s up to the Soviet takeover in 1940, which lasted only one year before the Germans invaded during World War II.

“All during this time, Pick’s life was falling apart,” Cassel says. “He lost his job under the Soviets. He lost his house. When the Nazis came in, they put him and his wife and son, along with other Jews whom they didn’t murder, into a Jewish ghetto in Šiauliai.” It was in the Šiauliai ghetto—where conditions included severe food shortages, disease, and overcrowding—that Pick began writing a memoir, chronicling atrocities committed by the Germans, who murdered up to 90 percent of Lithuanian Jews, aided by Lithuanian collaborators.

A Project Takes Shape

Cassel learned of the Pick journal through a fruitful connection that began in the early 1990s, when an Israeli folklorist named Dov Noy gave a lecture at Penn. “I knew he was involved in reprinting a version of the Ginsburg and Marek folk music collection,” Cassel says. “So, I went to his lecture and told him about my grandfather. From him, I learned that I had a cousin in Israel. My cousin and I corresponded over the years, and in 1997 he let me know that the Pick memoir had been published in Hebrew in Israel.” The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington D.C., subsequently purchased the Hebrew manuscript, digitized it, and posted it on its website, where Cassel found it.

Cassel says he started to “bug” the museum about translating the memoir into English. Coincidentally, the museum was in discussions with Gabriel Laufer, who had worked on previous translation projects. “Laufer grew up in Israel, spoke fluent Hebrew, and had an interest in the memoir,” Cassel says. “The museum put the two of us together.”

Around the time that Cassel began working with Laufer, he took a course in modern Jewish history, taught by Beth Wenger, Moritz and Josephine Berg Professor of History, and Benjamin Nathans, Alan Charles Kors Endowed Term Associate Professor of History. Cassel later asked Wenger to serve as advisor for his Capstone—the culminating project for M.L.A. students—and the Pick memoir seemed the obvious choice for his research topic.

“I have read many, many Holocaust memoirs,” says Wenger, who is also Associate Dean of Graduate Studies at Penn Arts & Sciences. “As I began to read his project, even in the early stages, I just kept thinking, ‘This is as powerful, as interesting a memoir as I have ever read. It should be widely accessible to the reading public, to educators, to people who teach about the Holocaust and Holocaust memory and in all sorts of venues.’”

Tragedy and Courage

The memoir’s title, Notes from the Valley of Slaughter, comes from the Bible and aptly represents some of the book’s contents. One of the more horrific stories involves an edict passed by the Nazis forbidding Jewish women to give birth.

“The doctors in the ghetto were faced with the issue of what happens if a woman did give birth,” Cassel says. “The Nazis might kill the whole family and possibly the whole ghetto. The doctors had to persuade or force pregnant women to have abortions. But in the end, there were live births, and there are two descriptions in the memoir of what the doctors did with babies who would otherwise have lived.”

There are stories of courage as well, including one involving a proposed mass execution for the crime of food smuggling. The Šiauliai ghetto, like most ghettos, had a Jewish Council set up by the Nazis and made up of Jewish men tasked with administering ghetto life.

In response to the smuggling incident, the Nazis instructed the Šiauliai Jewish Council to make a list of 50 people to be shot. “As Pick describes it, the council members stayed up all night discussing this. In the morning, their faces were all white,” Cassel says. “But he learned that when the council gave the list to the commissioner, they had put their own names at the very top. Because they were needed to administer the ghetto, the Germans relented and opted for a hefty fine instead.”

In addition to its disturbing scenes, the book’s archaic language presented challenges. Cassel says Pick’s parents had wanted him to become a rabbi and gave him a very traditional 19th-century Jewish education, including intense study of the Talmud, the Bible, and rabbinic writings, and these formed the basis of his mode of expression. Cassel credits Laufer with doing the “heavy lifting” when it comes to the translation work. His own role was to make the text readable for a contemporary English-speaking audience.

“The text itself is written in a kind of Enlightenment Hebrew that’s difficult even for Hebrew readers to grasp,” Wenger says. “It also contains lots of intertextual references. Andy annotated the text in such a way that you can understand the author’s references to religious texts while still keeping the flow of the memoir. It reads beautifully.”

A Sense of Duty

Throughout the painstaking work, Cassel was sustained by a sense of responsibility to the project. “The more I got into it, the more I felt it as a duty,” he says. “I thought, ‘I have to put this into words that people can understand and make sure that the world gets to read this.’”

Another notable aspect of the project, adds Wenger, is the distinctive voice of Aharon Pick. “Sometimes he can be very sarcastic and biting, and he’s also a bit egotistical in certain moments. He had a fascinating life, becoming a prominent physician and then essentially being debased in society, but he also had a unique vantage point as a highly educated medical professional in this ghetto.”

Wenger knew the memoir deserved a wide audience, and she became invested in seeing it published. She connected Cassel and Laufer with Indiana University Press, which added the title to its well-known series of scholarship on the Holocaust.

Pick died from an illness in 1944. His last entry was dated June 7 of that year, when he had just learned about D-Day, writing, “Maybe this will finally liberate us.”

The memoir’s long journey into Cassel’s hands began after Pick’s death. “The Germans liquidated the ghetto as the Allies moved in, but before that, Pick’s son buried his father’s manuscript and fled before the Germans could deport him to a concentration camp,” Cassel explains. “He came back when the Russians had taken over the town, dug up the manuscript, and with it made his way to a displaced persons camp in Europe. From there he went to Israel, where he helped start a kibbutz and raised a family. He died in 1975. Pick’s wife was not so lucky.” In all likelihood, she was sent to Stutthof Concentration camp in Poland and died there.

“There’s just so much to be gleaned from this text,” Wenger says. “What Andy put together was so remarkable and so revealing that I became captivated by it. I’ve advised many wonderful M.L.A. projects, but none that were published by an academic press. It’s just been a pleasure for me as a faculty member, and as a historian, to be part of it.”