A Sustainable Past

Brian Rose Works with Soldiers, Children, and Other Stakeholders to Save Humanity’s Cultural Heritage

Two satellite photos of the ancient Roman city of Apamea are juxtaposed on the computer screen. On the left, a vertical line marks an ancient colonnaded street crossing the smooth brown earth. In the right photo the street looks like it’s on the moon.

The first image of the site, located in western Syria, was taken in July of 2011; the second just nine months later. The “craters” covering the landscape are pits dug by looters. “Sites all over Syria look like this now,” says C. Brian Rose, James B. Pritchard Professor of Archaeology. “They dig one pit next to the other, next to the other, next to the other. And all of this material has been lost.”

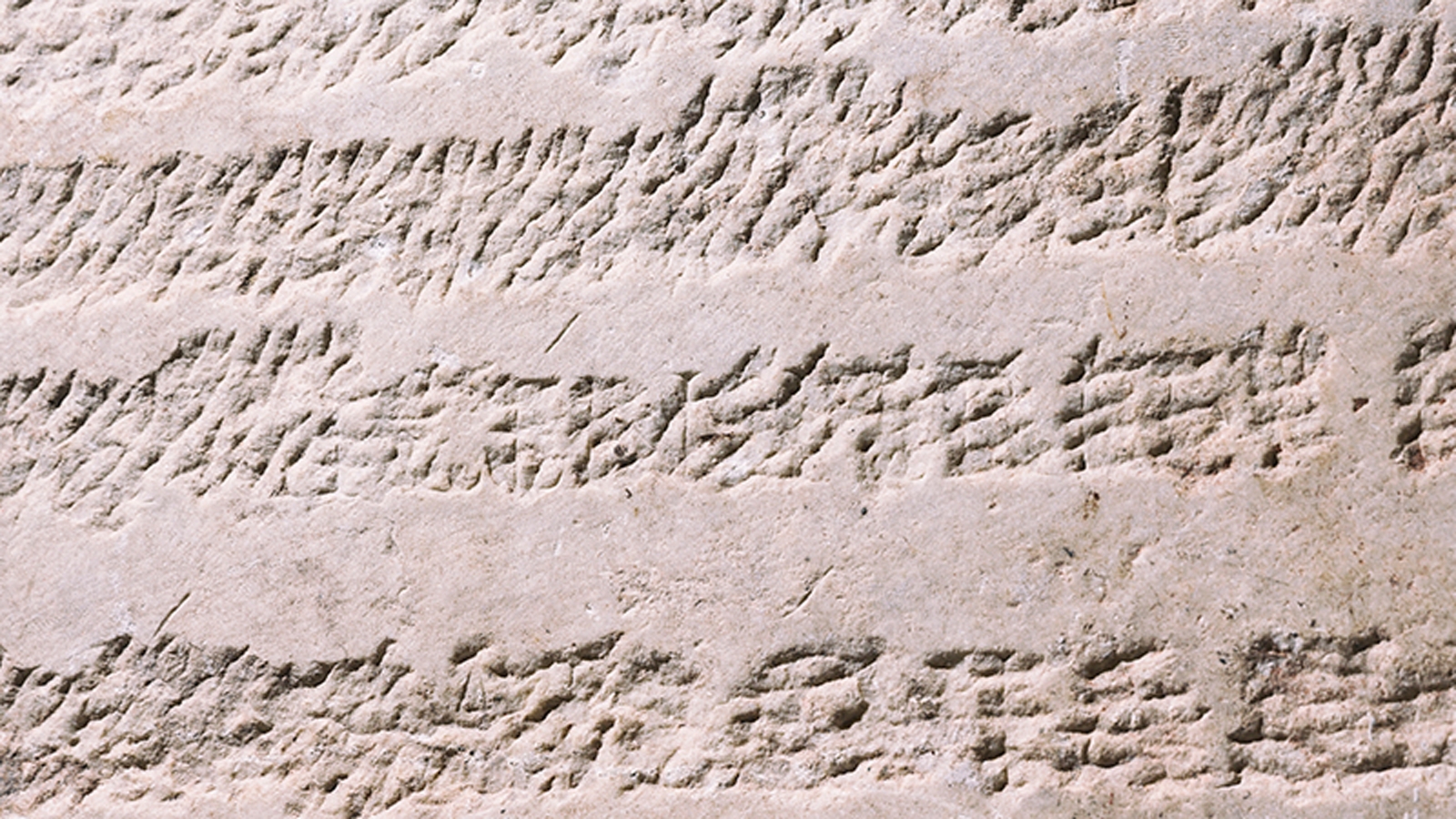

Ancient iconoclasm: In the Penn Museum, Brian Rose stands next to a column from the throne room of the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah on which a pagan image has been hammered out. The previous photo shows a detail of a chiseled-out inscription of the Roman emperor Domitian.

Ancient history and modern politics are inextricable for Rose, who has co-directed excavations at Troy, on the northwest coast of Turkey, since 1988, and Penn’s massive Gordion project in central Turkey since 2007. He was the first to run the war desk created by the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) in 2003 in response to the looting happening in Iraq. He’s seen colleagues forced to move their work from Iran to Iraq to Syria to Turkey as war followed war.

Now he watches as the Islamic State in Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) loots and destroys archaeological treasures. In February a United Nations resolution condemned the devastation of cultural heritage in Iraq and Syria by ISIS and the al-Nusra Front (ANF), “whether such destruction is incidental or deliberate,” and the income generated for these groups by stealing and smuggling antiquities.

“It was frightening and nauseating,” Rose says of the video of ISIS members smashing statues in a Mosul, Iraq, museum with sledgehammers and a jackhammer. Iconoclasm—the deliberate destruction of icons—has been around for millennia, but he realized he was watching a brand new approach. “ISIS has its own branch of digital humanities,” he says. “There were slow motion effects. There was special lighting. Their marketing department has conceived of this as a way in which to pull in recruits. And it seems to be working. But it’s beyond my powers of comprehension.”

At present, says Rose, scholars can only monitor the extent of the destruction. He believes that the archaeologist’s biggest responsibility today is to teach cultural property protection at every age level. “If you get to individuals while they’re children and teach them respect for difference, for cultural heritage and the need for protection, you are investing in the future in the hope that they will be more aggressive in their efforts to protect cultural heritage.”

Last summer his team at Gordion, led by Gordion Assistant Director Ayşe Gürsan-Salzmann, began teaching the area’s children about the significance of the place where they lived. The royal city of King Midas, Gordion was the capital of the Phrygian people who dominated much of Asia Minor during the first millennium B.C. The site was inhabited for more than 4,500 years, and Penn’s dig there, which dates back to 1950, is one of the most important excavations in the world.

Rose sees the continuum from past to future in everything he does: “You want to leave as much as you can, not only for the next generation, but generations, plural, of archaeologists who will come in armed with better tools and techniques than those we currently possess.”

That means not only keeping extensive records but avoiding damage to the site whenever possible. As part of the Digital Gordion project launched in 2007, the team has been digitizing decades’ worth of past records and is using 21st-century tools to help map and preserve the different layers of the site. They’re combining magnetic prospection—which gives a rough picture of what’s below the ground without digging—with radar data, information from previous digs, and aerial views with GPS information taken by drones to put together a three-dimensional map showing the site at different times through history.

“We’ve been able to model the landscape and map a series of settlements and the land around them far faster than ever before,” says Rose of the new digital tools. “In areas like Syria that’s vital because we’re running out of time to record the cultural heritage of the Near East.

“Now, these tools are not enough to make anyone feel better about the destruction of cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq, but what is feasible?” he asks. “You could, in theory, send the entire U.S. military to Syria to stop the iconoclasm, but that’s not a practical solution. Mapping these areas, photographing the looting, charting the destruction, and then making sure you have a sufficient number of cultural heritage outreach programs for the relevant stakeholders. And the relevant stakeholders include children in every country.”

In 2003 Rose expanded his teaching to another new type of student: soldiers. Charged with finding a way to stop the looting in and protect the cultural heritage of Iraq and Afghanistan, he developed a training program for the U.S. troops who would be responsible for protecting historical sites. After working through initial resistance from both the military and academics, he began speaking at military bases.

His first audiences hadn’t yet been to Iraq or Afghanistan, so Rose highlighted well-known tales from the Bible—the Garden of Eden, Abraham at Ur, Daniel in the lion’s den in Northern Iraq—that have been linked to discoveries in the area, to give the soldiers some association with the places. He also described Alexander the Great’s challenges in Afghanistan, which mirrored the hurdles the U.S. troops were facing. He named everyday things which came from Mesopotamia: the first dictionaries, first schools, and first code of law, as well as coffee and soap.

Troops who had been deployed began to tell Rose about the things that they themselves were seeing. “So I learned from firsthand experience about a lot of these sites that I had never seen, and that no one but the soldiers was seeing now,” he says. “They relate to the culture in ways I can’t imagine.” The soldiers he'd worked with would send him photos and tell him how they’d stopped people from looting or changed a construction site when traces of ancient walls were found.

Eventually Rose and the soldiers also began to talk about similarities between what they were experiencing and war as described in the Homeric epics. “In the Trojan War there’s a Greek soldier named Ajax who experiences temporary insanity, a kind of PTSD, and commits suicide,” says Rose. “This happens in the armed forces, in almost every country, I suppose.”

Rose has begun to work with Kimberly “Max” Brown, GR’04, a Penn Ph.D. in archaeology of the Mediterranean world who is co-director of research development and grants manager for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, and other Penn faculty and VA staff to create EternalSoldier.org. Their goal is to empower veterans by showing that the emotional, spiritual, and psychological experiences of war have a timelessness that unites all warriors.

At the same time, Rose takes kindergarteners and scout troops through the Penn Museum and has developed a program on archaeology for kids in long-term care at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He continues to work with the U.S. military and the Navy ROTC students at Penn. He’s trying to get other nations to commit to cultural history training for soldiers. “We need a United Nations of archaeologists,” he says. “Antiquity has never been more relevant to the modern world than it is now. We can’t know where we are unless we know where we’ve been. That’s why scholars specializing in the ancient world are vital to an understanding of what’s happening all around us, both in war and in politics.”

He remains an optimist, but one who works nights and weekends. “There’s never a glass I see as half-empty,” he says. “But we’re all going to have to work a little harder if we’re to have a future that continues to feature the great monuments of world civilization.”