When VanJessica Gladney was growing up, her family moved around a lot, and she noticed that the history books in each state were different.

“In Georgia I learned about the Civil War as the ‘war of northern aggression,’” she says. “In Oklahoma I learned more Native American history than colonial history. And then I got up to Massachusetts and learned that Boston won the Revolutionary War for everybody and saved the day.”

As a Penn student, that observation came back to Gladney, C'18, as a powerful reminder that when it comes to history, who is doing the telling determines the story being told. Today, she is one of several alumni, undergraduates, and graduate students who are part of the Penn Slavery Project, an effort to retell the story of Penn’s involvement with slavery in the University’s earliest decades.

Slavery is often associated with the South, but from the Colonial era until the Civil War, the entire country’s economy was interwoven with and dependent upon the slave trade. Tiny Rhode Island, for example, launched about 60 percent of slave-trading voyages across the Atlantic Ocean. Rhode Island also profited from the export of food and supplies to sugar plantations in the Caribbean, where hundreds of thousands of enslaved people were brought from Africa.

Over the past two decades, there has been a growing public recognition of what historians have long known—that the tentacles of slavery reached well into the northern colonies and states. Laws prohibiting slave-holding in the North were enacted only gradually, and commerce associated with slavery and the products of slave labor continued well into the 19th century. Monuments to prominent historical figures who owned enslaved people—in both the North and South—have been removed or renamed across the country in recent years, often sparking controversy.

Some of the country’s oldest universities have also reexamined and acknowledged their own ties to slavery and slaveholders. In 2003, Brown University became the first Ivy League institution to appoint a committee to study the University’s links to slavery. The connections were many and deep, including the fact that an early member of the university’s Board of Trustees had captained transatlantic slave ships, and that the school’s early benefactors, the Brown family, had owned enslaved people.

Other universities followed suit. Most notably, Georgetown University acknowledged a history of slave ownership and has taken a number of steps toward restitution, including offering preferential admission to the descendants of enslaved people it held or sold. Other southern schools, such as Emory University and the University of Virginia, created their own commissions and investigating bodies.

“Some of this reexamination has to do with the way people in the field of history are thinking about slavery, not as something separate from capitalism, but as something that really made the economic motor go.”

Yale, Princeton, and Harvard have also grappled with their own entanglements, and campus debates have challenged long-held assumptions of northern innocence.

“Some of this reexamination has to do with the way people in the field of history are thinking about slavery, not as something separate from capitalism, but as something that really made the economic motor go,” says Kathleen Brown, David Boies Professor of History, who studies gender and race in early America, slavery, and the transatlantic abolition movement.

Brown had questions about Penn’s public statements regarding slavery, which until recently asserted that it had found no evidence of direct involvement with slavery or the slave trade. She thought more study might be needed to uncover a fuller picture. “Even though we don’t think of Pennsylvania as being one of the major slave colonies, so much of the North American economy was implicated,” she says.

In 2017, Brown and Walter Licht, Walter H. Annenberg Professor of History, were teaching a course called Deciphering America, which looked at American history through primary documents, historical figures and images, and cultural artifacts. One day in class a side discussion arose about Princeton University’s relationship to President Woodrow Wilson, a former Princeton president who held segregationist views, and the debate about whether his name should be removed from campus buildings.

Gladney, who was enrolled in the class, had mixed feelings. “Honestly, I don’t know how I feel about renaming buildings or tearing down statues,” she says. “I think that in taking away mementos of powerful figures who have done bad things, you run the risk of letting them off the hook. When we stop talking about them, we eradicate a whole group of people who have already been erased from our history. Instead, we should bring the enslaved people into the narrative rather than just pushing the [slave-holders] out.”

Brown asked if any students from the Deciphering America class would be interested in researching Penn’s connections to slavery as an independent study project, and Gladney, Brooke Krancer, and Dillon Kersh responded enthusiastically.

As a start, Brown introduced the students to Mark Lloyd, Director of the University Archives and Records Center, and put them in contact with the staff of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. That fall, Brown met weekly with the students as they drove the investigation mainly on their own, while she served as a liaison with the University and helped guide the students in working collaboratively.

Some of the student autonomy, Brown says, came from the fact that she already had a full teaching load and administrative duties, and didn’t have the availability to direct them with a heavy hand. But she also knew that undergraduates had played an important role in some of the projects at other schools. “Graduate students are on a pretty linear path toward degree completion,” she notes, “but undergraduates have the flexibility to do research that’s not necessarily going to be their life’s work."

Brown says the group also benefited from the guidance of a doctoral student in history, Alexis Broderick Neumann, Graduate Fellow at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at Penn Libraries. Broderick Neumann had been appointed to the Provost’s Working Group on Penn and slavery, founded in January 2018 to further explore matters brought to light by the undergraduate group.

“My own research focuses on issues related to race, sex, and violence in the U.S. South during slavery and Reconstruction,” says Broderick Neumann. “This project has underscored the importance of uncovering and communicating the history of slavery to a broad audience.”

Into the Archives

The students had a wealth of information at their fingertips—archives from the University, the Pennsylvania Gazette, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and the Library Company of Philadelphia, not to mention a database of Pennsylvania tax records. They could pore over legal documents like wills and tax receipts, private papers like lecture notes, and public records, including newspaper advertisements for runaway slaves. The students realized early on that constructing a story from raw materials would be a huge undertaking.

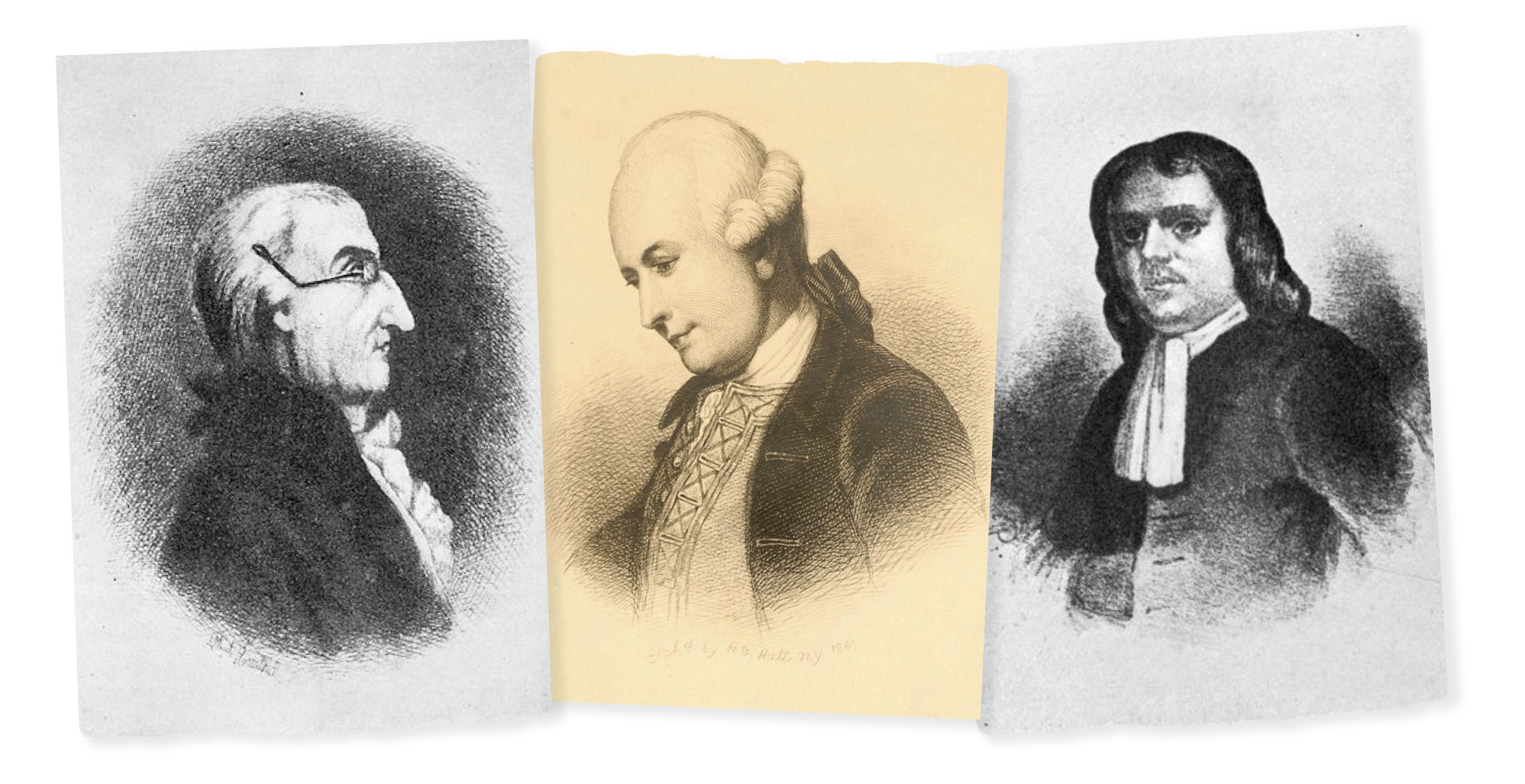

They started with the University founders and early trustees, men who held economic and political power in the colonial days. Given the relationship between slavery and capitalism, the students speculated that these high-profile men would be directly or indirectly connected to the institution of slavery. Dillon Kersh, C’20, realized that the archive could not answer all his questions and that concrete evidence is difficult to come by.

Kersh researched cousins who were early University trustees: Edward Tilghman, Jr. and James Tilghman. The cousins, from a wealthy Maryland family, practiced law in Philadelphia.

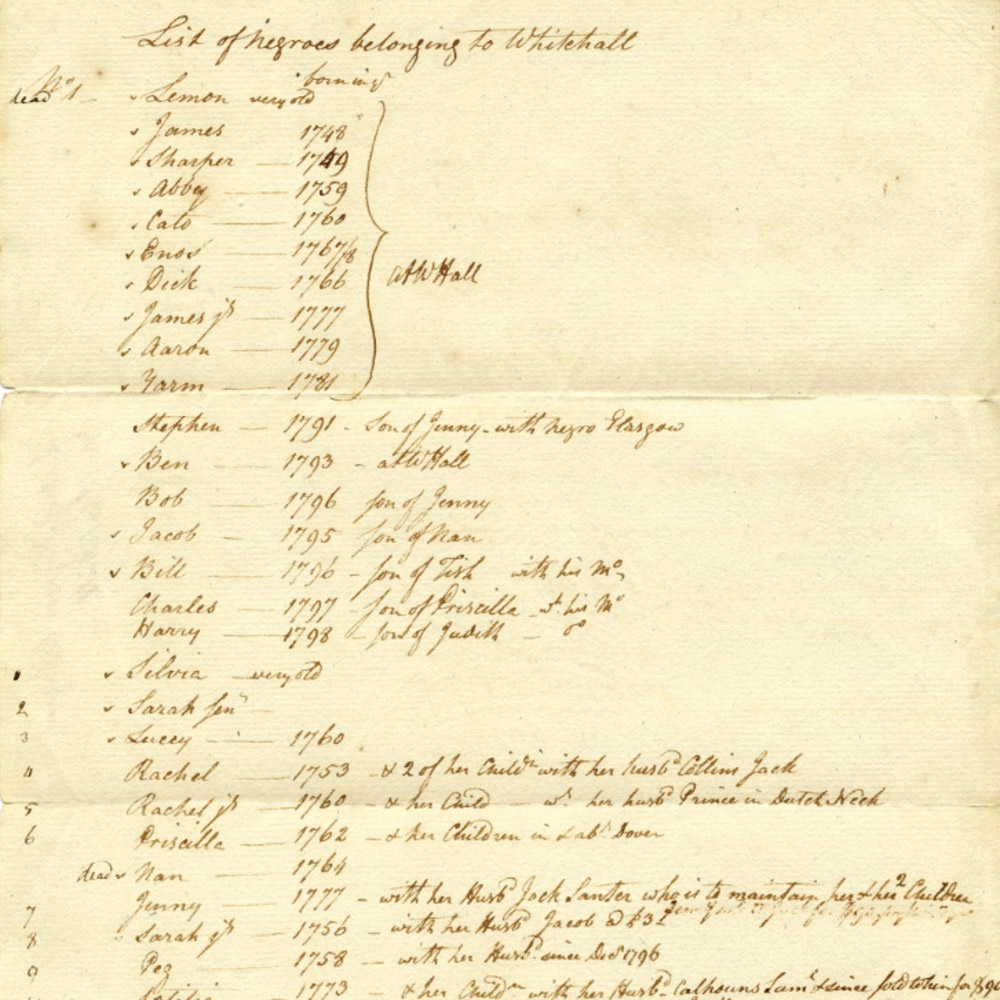

At the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Kersh found records indicating a deed transfer from Edward Tilghman to Benjamin Chew, a relative and fellow University trustee. The deed indicates that Edward’s father gave him a property called Whitehall Plantation, which he then sold to Chew.

This finding was a boon. “The Whitehall Plantation records held by the Historical Society are some of the most detailed records that we found, with names, birth years, familial relationships, and even clothing sizes of enslaved people,” Kersh says. “It’s a peek into the lives of enslaved people that we haven’t found in any other context.”

But Kersh was frustrated. The deed proved that Edward’s father and uncle held enslaved people, and it proved that with the sale of the plantation, he benefited from the economy generated by slavery. It did not prove that Edward himself was a slaveholder, though Kersh suspected that was the case. “Edward was wealthy in his own right and his family in Delaware and Maryland were some of the largest slaveholders in the mid-Atlantic,” says Kersh.

In summer 2018, Kersh found the evidence he’d been looking for since the previous fall. Letters at the Maryland Historical Society reference several enslaved people held by Edward, and records in Pennsylvania prove that he emancipated at least three enslaved people in the 1780s and 1790s. It took months, but Kersh found his answers in the archives.

Other students shared his experience of discovery—and dead ends.

Brooke Krancer, C’20, focused her research on the wills of trustees. “I was looking for mentions of enslaved people in the wills—were they freed or passed on to family members?” she explains. “That is definitive proof of the fact these men held enslaved people and it starts to show what happened to the people they held.”

Even when wills showed that trustees held slaves, stories were incomplete. William Allen, a founder of Penn who served as mayor of Philadelphia in 1735, freed the people he held in bondage in his will, but he did not name them, a far cry from the detailed records of Whitehall Plantation. “He referred to them as Negroes,” Krancer says.

Another trustee, John Cadwalader, wrote several versions of his will. In some, he freed a man called James Sampson and his family. But in the fifth and final version of the will that Krancer located, there is no mention of Sampson. “Did he free them before he died, or did he not want to free them anymore? It’s very frustrating not to know,” she says.

Carson Eckhard, C’21, had to turn to other sources to fill in the gaps in the archive. She joined the project in spring 2018 with a focus on the medical school. When it was founded in 1765, the medical school was only loosely affiliated with the liberal arts school.

“Things like charter documents of the medical school weren’t always preserved in University archives, because they weren’t as connected,” she explains. “But there are lots of notes from old students and correspondence between professors and other notable scientists. That does a decent job of filling in the gaps.”

Newspaper advertisements also provide a window into to the medical school and connections to slavery.

Eckhard reports, “The information that we’ve found so far indicates that 30 percent, and some years as many as 60 percent, of medical school graduates were from the deep South. Penn advertised very heavily there.”

The connection between medical schools and slavery is one that many universities contend with. The Medical University of South Carolina, for example, had an endowed chair named for J. Marion Sims, an alumnus known as the “father of modern gynecology.” Less discussed is the fact that he practiced his pioneering surgical techniques, without anesthesia, on enslaved women named Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey, among others whose names were not recorded. The chair has recently been renamed.

In light of this national legacy, Eckhard knows she has more work to do.

“I’m interested in looking deeper into the medical school, exploring connections to the South, and investigating how the school obtained anatomical specimens,” she says.

For Krancer, Eckhard’s research represents the importance of growing the number of students involved in the research.

“With more people, there are more avenues to explore,” she says. “It’s largely thanks to Carson that we’re exploring the medical school, and that’s resulted in so much information. I want more of that—new people, new energy, and new creative thought.”

The Family Tree

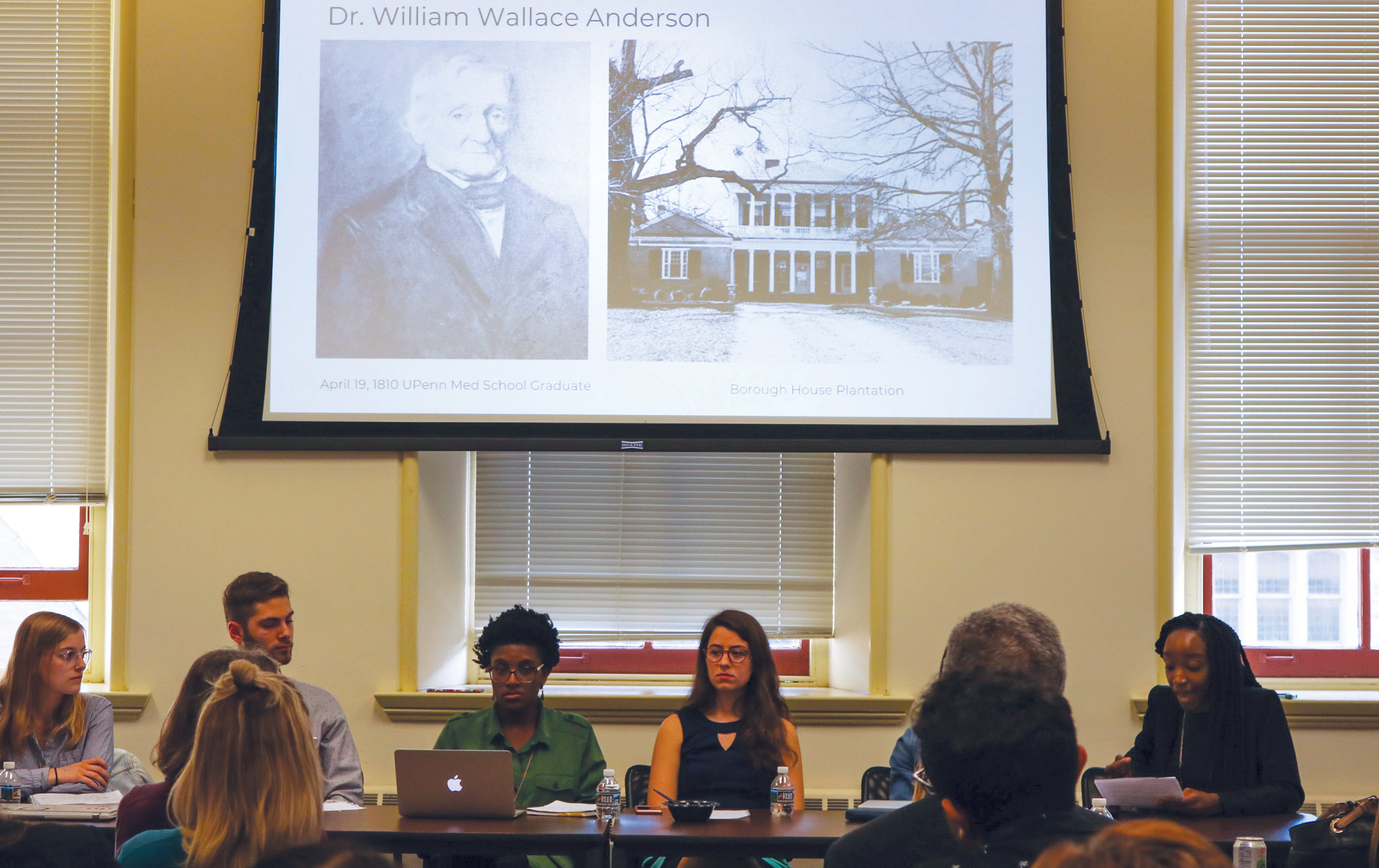

Breanna Moore, C’15, knew of some connections between Penn and slavery before the research began. While she was a student, a family member interested in genealogical research discovered a Penn connection: Moore’s great-great-great-great grandmother, Binah, and her six children, were enslaved by William Wallace Anderson, a graduate of the medical school’s class of 1810 and father of a Penn alumnus.

“Anderson’s plantation where they were held is only three miles from my grandmother’s house,” Moore says. “I would pass it every Sunday and I was unaware of its existence and physical proximity, just as I was unaware of my ancestor’s enslavement.”

Moore started doing research on her family on her own time, and continued to do so after she graduated. When she heard about the Penn Slavery Project, she reached out to Brown to share what she’d found. Moore joined forces with the team and continued her investigation.

She used census records, Ancestry.com, wills, church baptism records, estate and inventory appraisals, death records, and a sharecropping contract to trace her family tree. Like the other students, Moore found answers and dead ends.

“Sometimes it’s a challenge even to locate wills and other records,” she observes. “African Americans weren’t named in the federal census records until 1870. The South Carolina 1868 state census and 1866 tax records that listed freedmen were very helpful.”

“In fall 2016, one year after I graduated from Penn, only 751 African Americans were enrolled. This is a direct legacy of slavery and evidence of the inequalities that persist in African American communities.”

The research made Moore realize the extent to which legacies of privilege and discrimination pass through family lines.

“In fall 2016, one year after I graduated from Penn, only 751 African Americans were enrolled. This is a direct legacy of slavery and evidence of the inequalities that persist in African American communities. Dr. Anderson and his son graduated from Penn in 1820 and 1849. It took over 200 years for someone from my family lineage to attend an Ivy League institution. It took over a century for my family to have access to educational institutions to become literate and obtain high school diplomas. Limited access to education still exists.”

Looking Back to Move Forward

In June 2018, Penn President Amy Gutmann announced that as a result of the history uncovered by the Penn Slavery Project, the University had joined the Universities Studying Slavery consortium (USS). As a USS institution, Penn joins universities across the country in confronting not only how the roots of higher education are entangled with slavery, but also how educational inequality remains a persistent issue.

Joining the consortium is an important step for the student researchers, who want the project to grow and the conversation to expand beyond Penn’s campus.

“What happened during colonial times is tied to today,” says Krancer. “It’s important to present this research to the greater community, because it is not just the story of Penn, it’s the story of Philadelphia.”

It’s the connection to today that has motivated the group to pursue this challenging research.

“In addition to the outright suffering slavery causes, there is also a lasting pattern of obstructed opportunity for people of color,” Brown says. “For almost any other immigrant group, you can trace the moment when they became ‘white’ enough to have white privilege. Not so for people of color, who’ve been systematically shut out of things like the GI Bill, mortgages, and even Social Security benefits due to the seasonal nature of jobs they held.”

Gladney, Kersh, Krancer, Eckhard, and Moore see that what they find in colonial-era tax records or legal documents has a direct connection to present-day realities of discrimination and inequality.

“Historical research really comes alive for students when they can see that it has a potential to change a conversation they care about,” Brown observes.

Changing the conversation and tracing complicated legacies means bringing more voices to the table and widening the audience, within Penn and outside of it. Arielle Brown, Public Programs Developer at the Penn Museum, observes that the questions the Penn Slavery Project is asking—about the inextricable links between slavery and the early American economy—are similar to growing trends in the museum world to reflect on collections and ties to the history of enslavement and colonization. The University has a large collection of cultural holdings and a public face—a perfect opportunity to invite community members to be part of reexamining history and telling long-buried stories.

Broderick Neumann hopes to work with the undergraduates to develop an exhibit on Penn and slavery for the Van Pelt Library. She and Kathleen Brown will co-teach a class on the topic this fall—it will no longer be an independent-study project. “I have been blown away by the work, dedication, and insights of these students,” says Broderick Neumann. “They are incredibly rigorous, have the utmost respect for the sources and the research process, and they are keenly aware of the importance of this subject. I’m looking forward to continuing to work with them on their archival research skills.”

When it comes to complicated legacies, VanJessica Gladney, who majored in English, was especially struck by what she learned about Isaac Norris, a University trustee in the 1750s whose family held enslaved people and who selected the inscription for the Liberty Bell:

Proclaim LIBERTY throughout the Land unto all the Inhabitants thereof.

“The irony is that the Liberty Bell later became the symbol for the abolition movement,” says Gladney, “so this focus on personal history versus family history and prestige is an interesting thing to look at."

In February, she published an article about the Penn Slavery Project in 34th Street magazine, and in the spring, the University sent her, along with Broderick Neumann and Arielle Brown, to the Universities Studying Slavery Conference in Virginia. This fall, Gladney began working for Penn on the public presentation of the Project’s research findings. She already has ideas about telling long-buried stories—she’d like to see the University add explanatory plaques to statues and buildings honoring controversial figures instead of removing them.

“As an English major, I’m fascinated by the way we talk about history, by the way we write about history. So I want to be a part of helping the University tell its history in as holistic a way as possible.”