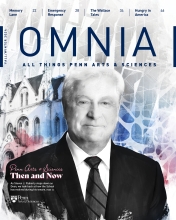

During Steven J. Fluharty’s time as Dean of Penn Arts & Sciences, the School expanded and evolved, thrived during a pandemic, and received the largest gift in its history. Yet Fluharty’s connection to Penn started much farther back than his nearly 12 years as dean. When he steps down in December, it will mark nearly five decades since he first stepped foot on Penn’s campus as an undergraduate.

Let’s go back to 2013. Having started out as an Arts & Sciences undergraduate, what did it feel like to become the person leading the School?

It was just a thrill. And for the past 11 plus years, despite tumultuous times, it’s been a great position to be in at Penn. The School of Arts & Sciences is the heart and soul of the University. And to get to lead it and build leadership teams was fantastic.

You went from your freshman year to completing your PhD in record time. How did that come about?

I was very fortunate to make a connection with then-Provost Eliot Stellar in my first year at Penn. He was a world-famous neuroscientist, and he helped me find my way into the University Scholars Program, which made it possible to begin post-baccalaureate studies as an undergrad. I was doing lab research by my sophomore year and even got a National Institutes of Health grant as an undergrad.

What was one of your proudest Penn moments as a scientist?

My own work was in neuroendocrinology—the action of hormones in the nervous system. I’m probably most proud of my lab’s role in discovering how a hormone, aldosterone, and a peptide called angiotensin, acted in the brain to produce thirst and salt appetite, which are critical to blood pressure regulation. Years later it became a citation classic in the study of ingestive behavior, but more importantly it was a conceptual discovery, the notion that hormones don’t just act additively, they act synergistically.

I didn’t plan any of this. When I look back, I don’t think that was necessarily a bad thing. If you don’t have a path, you can never go the wrong way, and I was very open to the opportunities that presented themselves.

How did your liberal arts background affect you over the course of a career that took you from scientific research and teaching to Senior Vice Provost for Research and Dean of the School?

I actually came to Penn wanting to be an English major. And even though Eliot steered me from English to neuroscience, I never lost my passion for the humanities—I was a would-be poet looking at life through a microscope. I retained a broad view that I think came from my appreciation of everything a liberal arts education provides: the ability to think creatively, to have an insatiable curiosity, to communicate effectively, and to form world views and conceptualize things. These are essential skills for scientists, and this broad view was absolutely essential for me as dean.

When you think about what’s next for the School, what are you excited about for your successor?

I think the School’s single greatest achievement during my time as dean was our strategic plan, Our Foundations and Frontiers, which clearly laid out important problems, as well as opportunities, for the School to make a big difference. But equally important was the process by which we got there. We took about 18 months and had nearly a third of the faculty involved in our working groups. We had staff, we had students—both graduate students and undergraduates. The buy-in from the process was almost as important as the priorities we identified. It’s a living document and has undergone some evolution, but it’s still the driving force for the School. I think what I see for my successor is a wonderful opportunity to do even more as the University identifies its priorities and puts necessary resources into those. If you look at In Principle and Practice [the University’s strategic initiatives] and Foundations and Frontiers side by side, you’ll see that the overlap is enormous.

What would your undergraduate self think of your Penn trajectory?

I joke with people, but it’s really not a joke—I didn’t plan any of this. When I look back, I don’t think that was necessarily a bad thing. If you don’t have a path, you can never go the wrong way, and I was very open to the opportunities that presented themselves.

What’s your favorite spot on campus?

To me it will always be the Bio Pond [James G. Kaskey Memorial Park]. When I was an undergraduate working in Leidy Lab, I started to eat lunch there. It was just peaceful. And it still is. Great place to hang out.