Space Into Place

In his new book, Cheikh Anta Babou, Associate Professor of History, captures the vitality of the Senegalese Murid diaspora.

If you walk down West 116th Street between Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X boulevards in central Harlem, you’ll almost certainly hear some French. Listen closely, and you’ll notice other languages you probably can’t identify: Wolof, Fulani, Mandingo, and others spoken by the thousands of West African immigrants who live there.

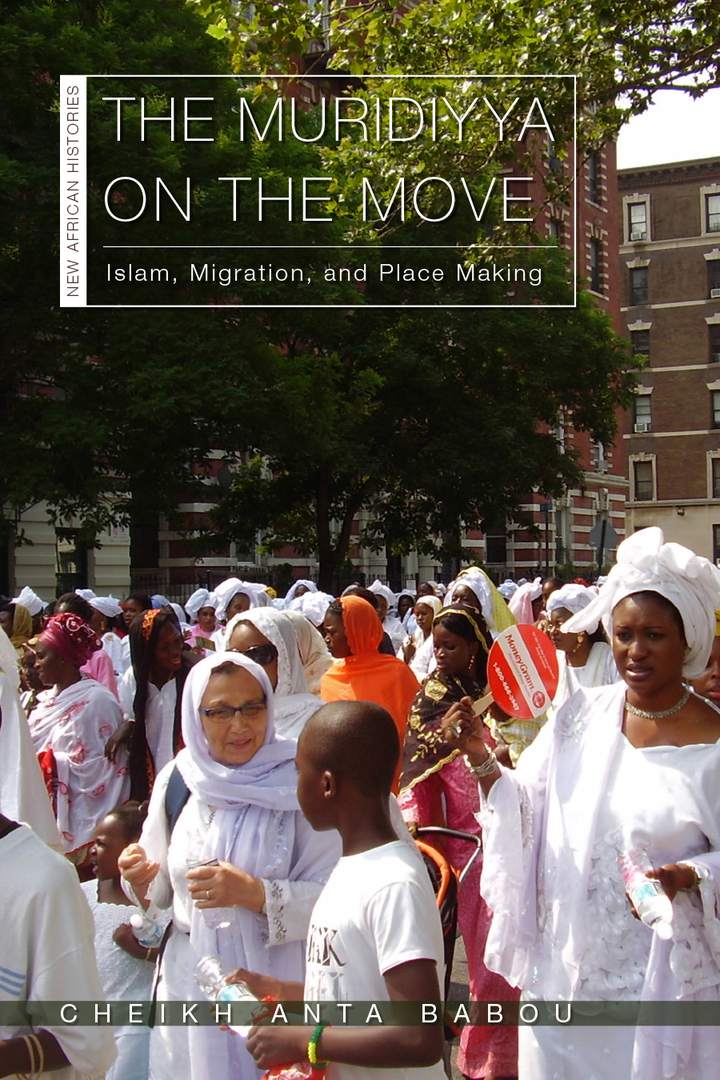

Since the 1970s, this neighborhood—known as Little Senegal, or “Le Petit Sénégal” by its francophone residents—has been a hub for the Muridiyya, a Sufi Islamic order founded in the late 19th century by Shaykh Ahmadu Bamba, a Senegalese poet and mystic who preached peaceful resistance to French colonialism and cultural assimilation. Far-flung from the order’s holy city of Touba, Senegal, it’s one of many vibrant Murid communities Associate Professor of History Cheikh Anta Babou highlights in his new book, The Muridiyya on the Move: Islam, Migration, and Place Making.

“The first time I visited Little Senegal, the streets were so lively, I believed I was in Dakar [Senegal’s capital],” says Babou, who joined Penn in 2002 and teaches African history and the history of Islam in Africa. “I was fascinated by what I saw—the shops, the restaurants, the festivals, the hair-braiders in salons, the way of dressing. How could these people, who came here without a penny and knowing no English, make themselves such an extraordinary life in a city where they should have gotten lost?”

Babou’s resolve to answer that question turned into The Muridiyya on the Move, in which he explores what it is about Murid culture that enables migrating disciples to thrive no matter where they settle. Murids make up one-third of the population of Senegal but account for more than half of the Senegalese diaspora—an estimated 2 million people living in established communities across Africa, Europe, and North America, and now spreading into South America and Asia.

As a master’s student in contemporary history at the Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar and a doctoral student in African history at Michigan State University, Babou discovered that the Muridiyya often went unmentioned in academic programs—and that when they did surface, it was in archives written by French colonialists and books authored by Western scholars. The stories they told did not match the ones Babou had heard from custodians of Murid oral history and his father, a Murid who knew Ahmadu Bamba personally.

“That political archival narrative about Ahmadu Bamba’s resistance being a threat to the French was central to academic narrative, and they completely forgot about this parallel cultural history that exists, mostly orally but also written in Arabic and local Senegalese languages,” Babou says. “I was able to access that treasure trove of documents, and that alternative narrative is what I have wanted to tell since I began studying the Murids before I came to the United States.”

For his new book, Babou also conducted 130 interviews with Murid men and women on three continents. As he’d expected, their insights varied from those in Western archives. For example, he found that the traditional economic theories of migration, maintaining that people emigrate primarily for financial reasons, do not apply to the Muridiyya, whose movement involves members of all classes, even the well-off.

“The Murids are not looking to turn new cities into their shop or their office. They are turning space into place, replacing the Senegalese society the French destroyed,” Babou says. “Space is generally perceived as a geometric reality defined by size and shape. Place, on the other hand, appears as a site of accumulated biographical experiences, a product of human agency that grows its significance from infused meaning and values.”

To create “place,” Babou explains, Murid migrants preserve and reproduce the values and events that define them, transforming foreign cities into their own havens. They gather in dahira (prayer circles during which they read poetry and socialize), host religious celebrations, tell religious stories, and sing religious songs—all activities French colonizers prohibited in public.

Babou also found that Western books and other media mischaracterized Murid migratory paths. In the U.S., France, Italy, Germany, and Spain—countries scholars underscore when describing Murid migration—interviewees repeatedly shared that they’d “step-migrated” within Africa before leaving the continent.

“Africa has the highest intercontinental migration of any continent, but whenever you hear about African migration, it’s Africans invading Europe—refugees or asylum-seekers crossing the Sahara, crossing the Mediterranean,” he says. “But out of every four African immigrants, three just cross a country border, never leaving Africa itself. The West just isn’t interested in talking about Africans in a nonpolitical, nonthreatening way.”

Babou hopes his new book will help counter Islamophobia and xenophobia by showing readers that Islamic and Western cultures are more compatible than common narratives suggest. The Muridiyya, he stresses, are an adaptive, peaceful group who can comfortably coexist with members of any other faith or background.

“Although my itinerary is different, I am part of this diaspora, too. I am somebody who grew up in the Murid heartland, and my father was a Murid himself,” he says. “To some extent, I am writing my own history.”