From Shylock to Rothschild

Liliane Weissberg examines Jews, money, and clichés in new exhibition.

As a scholar of German and comparative literature, it’s second nature for Liliane Weissberg, Christopher H. Browne Professor in the Arts and Sciences, to see literature as a window to deeper truths about society and culture. Take, for example, Shakespeare’s Shylock, the “bad” Jew who wants his pound of flesh, and his counterpart, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s “Nathan the Wise,” the upstanding, generous Jew. While the two have historically been used to demonstrate “the opposition between the good and bad Jew,” Weissberg points out, “nobody seems to have noticed … the commonality of both. Not only are they both moneylenders, they are both rich. What seems to top the question of good and evil is the presupposition of wealth.”

This presupposition is the subject of an exhibition that Weissberg recently curated for the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt, Germany. Called “Juden. Geld. Eine Vorstellung” (Jews. Money. A Show), the exhibit, sponsored by Deutsche Bank, is slated to run until October 6, 2013.

Weissberg became involved in the project over a year ago, when the museum’s director mentioned to her that they were thinking of doing a project that he called, “On Jews and Money.” According to Weissberg, her immediate reaction was “Why the ‘and’: Jews ‘and’ Money? Between Jews and money there is no connection except one that is constructed.” She goes on to explain, “That’s why we interrupted “Jews” and “Money” [in the show’s name] by full stops.” She also notes that the final phrase of the title, “Eine Vorstellung,” has a double meaning in German, encompassing a representation within a person’s own imagination, as well as a representation in the form of a theatrical production.

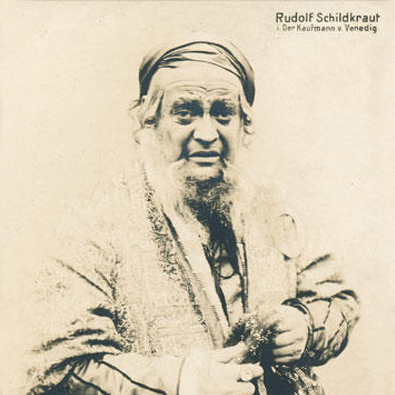

The exhibition’s staging sustains this dual meaning, referencing the devices of theatre while exploring one of the central clichés surrounding Jewish identity. Upon arrival in the entrance hall, museum visitors are met to their right and left by videos of actors putting on makeup and reciting lines for the roles of Nathan and Shylock.

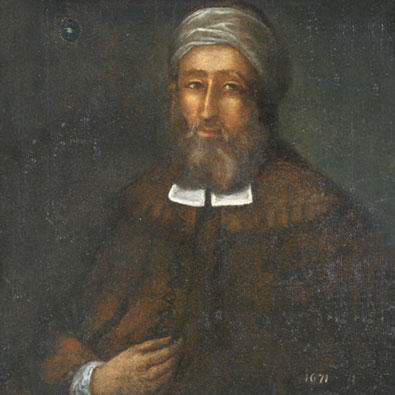

In the series of displays that follows, Weissberg and her collaborators present a range of objects and materials illustrating the historical role of Jews in the money professions in Germany and Austria, as well as the stereotypes surrounding this role. The progression begins with the Middle Ages, when the Catholic church solidified the position that lending money for interest was a mortal sin, but a path open to Jews, who were shut out of many professions. Visitors then move on to 17th and 18th century “court Jews,” who provided the princes of Germany with the goods and loans they needed to rebuild their states following the 30 Years War. The rise of Jews in banking and department stores in the 19th century is documented, along with accompanying caricatures.

The exhibit connects Germany’s inflationary crisis of the 1920s with increasing volume and venom of anti-Semitic propaganda, demonstrating that the way had been paved for the Nazis and the process of disownment of the Jews. The chilling final juxtaposition of this chapter is, as described by Weissberg, “a film that shows the removal of gold teeth from corpses in the concentration camps …. And as the last object at the end of the corridor … a Swiss gold coin of a series that was probably made from Jewish tooth gold.”

The topic is, obviously, one that arouses strong feelings—especially in Germany. Numerous articles and reviews of the exhibit have been appearing in the German press, and it has attracted some degree of controversy. But, Weissberg says, there are compelling reasons for returning to this charged territory, not the least being that today’s financial crisis has been accompanied by incidents and comments demonstrating the persistence of the old clichés.

The exhibit’s “epilogue” presents just a few examples of these clichés, including a prize-winning German novel that depicts a wealthy Jew, whose mother perpetually has money spilling out of her bag, as well as a thoughtful set of questions from Chinese media, addressed to the museum, asking for advice on how to teach their youth to have greater respect for money. With this conclusion, the exhibit leaves open the question of whether the “full stop” between Jews and money asserted by the show’s title may still be a work in progress.