Science/Fiction

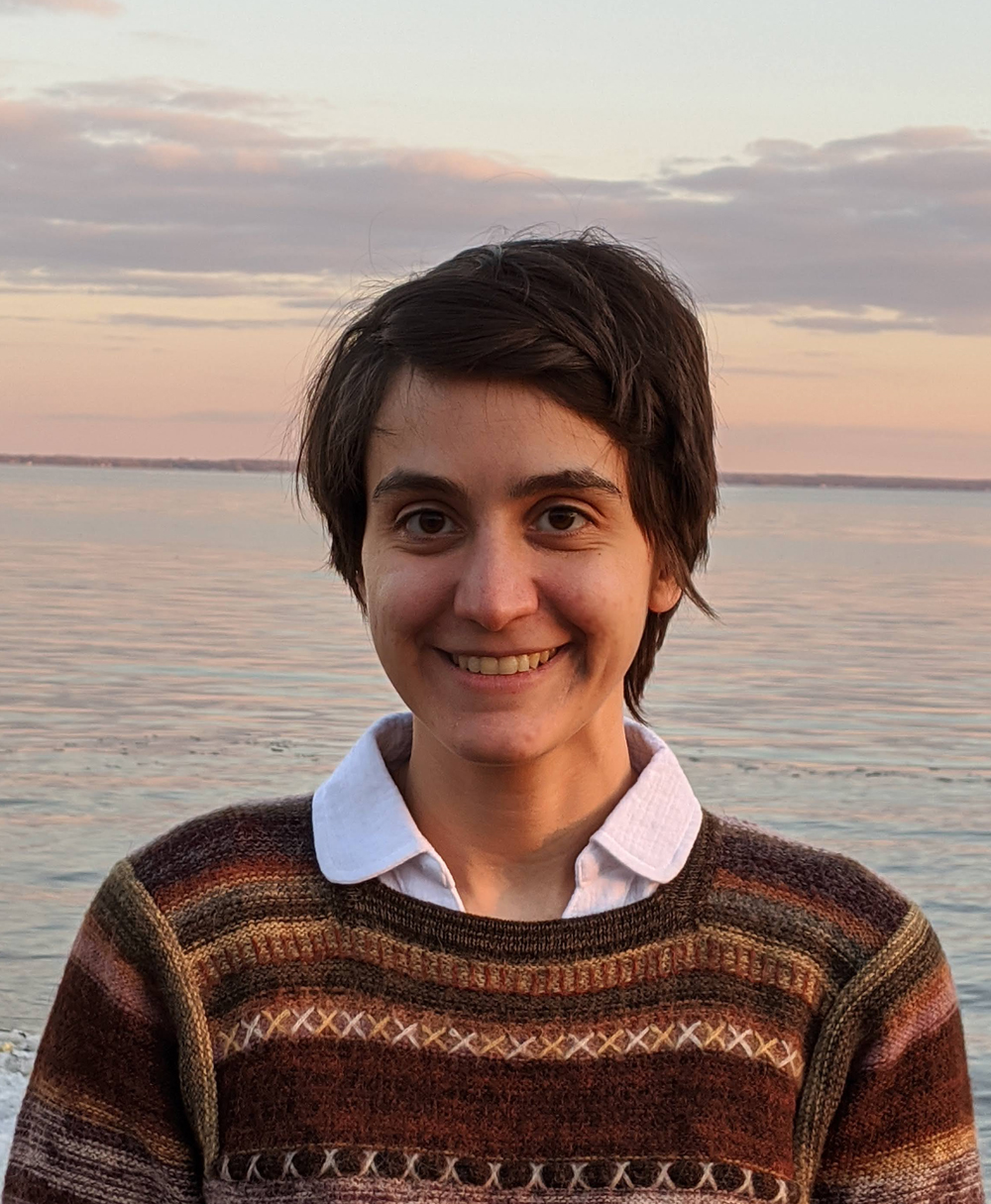

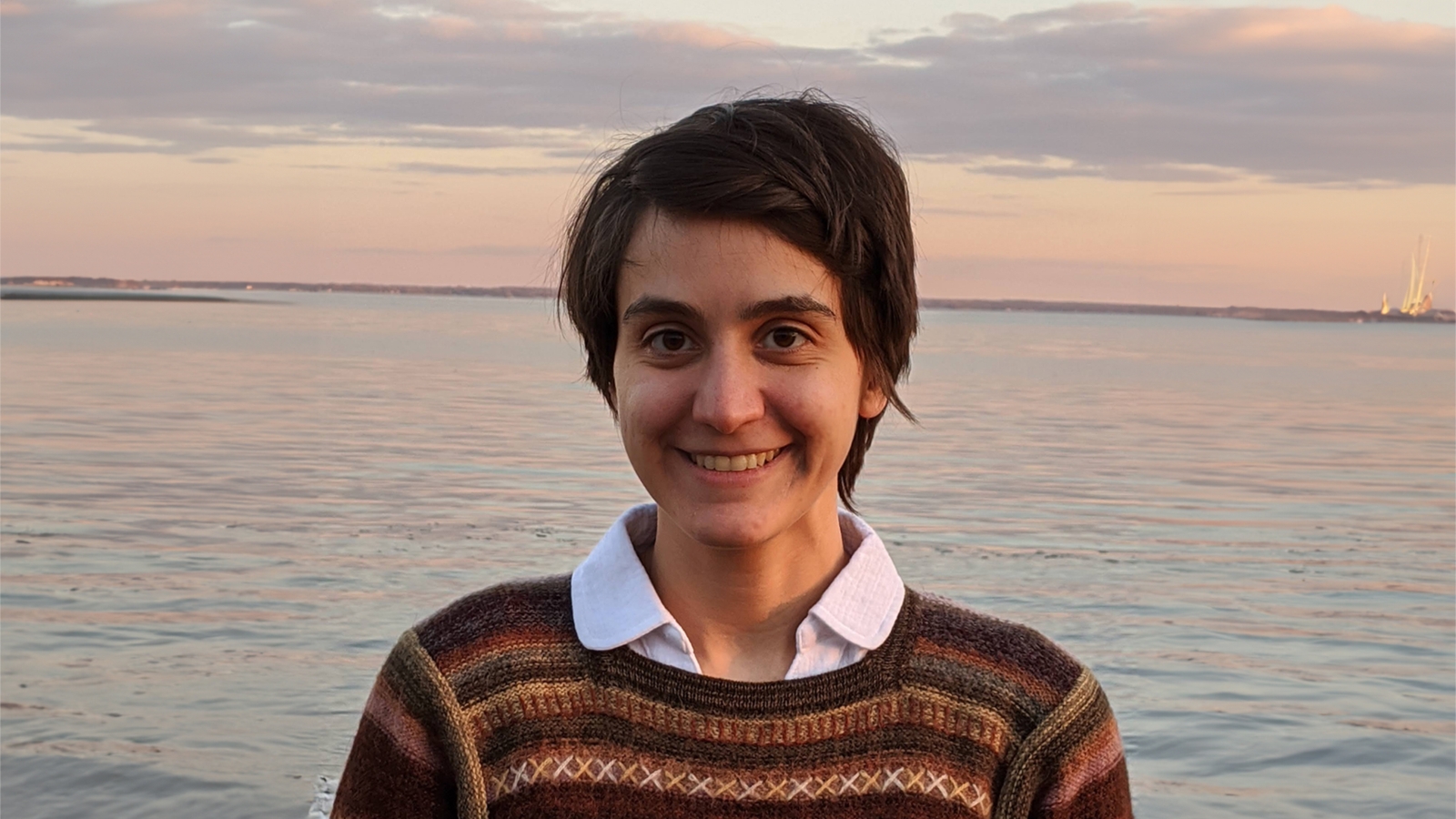

Doctoral candidate in English Aylin Malcolm’s class shows that when it comes to science, communication matters.

“When times get bad,” says Aylin Malcolm, “the medieval world seems more relevant than ever.”

As the world weathers the COVID-19 pandemic, talk has turned to the plague, a distinctly medieval threat. This is no surprise to Malcolm. “The humanities—history, literature, art—give us examples to look to, for good or bad,” they say. “There’s the plague, the use of zombie movies as a metaphor, and even the emergence of virtual book clubs and an emphasis on reading. I have a scientific background, but I’ve always been drawn to the value of the arts in times of crisis.”

Malcolm, a doctoral candidate in English and a fellow at the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities, studies medieval literature and how natural science was communicated and represented before the Scientific Revolution. In the spring semester, they taught a junior research seminar, Science/Fiction, which shows students the intersections between science and literature and how definitions of scientific knowledge evolve and reflect societal biases.

“We often think of science as objective and literature as subjective,” Malcolm explains. “But, as we’re seeing in our news every day, science is done by humans with all their interests and shortcomings. And just as important as scientific findings is how those findings are communicated.”

Course readings included texts such as The Blazing World, a 1666 work of science fiction written by Margaret Cavendish—dismissed as an eccentric in her time but who has been reconsidered in recent years—and contemporary writers such as Rebecca Roanhorse and Ted Chiang, whose work expands the canon of science fiction and adds perspectives missing from Western or Eurocentric traditions.

The COVID-19 crisis led Malcolm to make changes to the course. Classes were held on Zoom, and continued to meet at the regular time so students could gather together and maintain what Malcolm calls the “lively community” that is the Department of English.

“There is a lot of fear and anxiety right now,” Malcolm says. “Continuing the work I care about gives me a sense of normalcy. I want to say to students that even in a time like this, the work of the humanities is valuable.”