Roller Coasters With Buddha

Professor of Religious Studies Justin McDaniel’s new book explores growing Buddhist leisure culture across Asia.

Suối Tiên Amusement Park in Vietnam’s Hồ Chí Minh City is 248 acres of thrill rides (including a roller coaster through Buddhist hell), animal entertainment, carnival games, beach and waterpark, food, and other delights. There’s also Bodhisattva Square, the Goddess of Mercy Temple, a five-story statue of Avalokiteśvara, and more Technicolor cultural and Buddhist-themed areas and attractions.

Unexpected? Perhaps. Incongruous? No, says Justin McDaniel, professor of religious studies and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies.

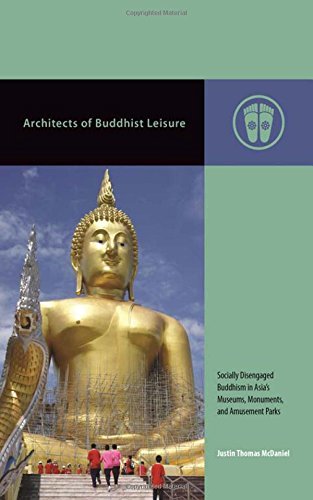

McDaniel’s new book, Architects of Buddhist Leisure: Socially Disengaged Buddhism in Asia's Museums, Monuments, and Amusement Parks, explores how Buddhist public spaces like Suối Tiên, the first Buddhist amusement park, reflect a growing Buddhist leisure culture across Asia—as he calls it, “socially-disengaged Buddhism.”

“Buddhism is often depicted as meditative and serious, and monasteries places of quiet reflection,” says McDaniel. When documenting Buddhist attractions while researching an earlier book, McDaniel says, “I realized that Buddhist scholars and students are missing a side of leisure life in Buddhist communities throughout Asia.”

A moment at one site particularly inspired McDaniel. “On a visit to Gilsangsa Monastery in Seoul, I took my then six-year-old daughter,” he says. “She had so much fun, and I looked around and saw Korean kids also having a great time. It sparked the idea for this book.”

The book’s first argument posits these spaces not only exemplify Buddhism’s growing leisure culture but also expose a false binary in Buddhism between secular and religious, public and private space. “Most Buddhists don’t distinguish between something that is sacred and something that is profane,” he says.

The non-sectarian sites, which charge nominal fees if any, are open to everyone, and people can experience as much or as little religion as they want. Buddhist or Buddhism-curious visitors will find diverse traditions, teachings, and aesthetics in one place, leading to McDaniel’s second argument: the spectacles, while different in scope and scale, are ecumenical in nature.

“This is where you’re seeing Buddhists trying to create spaces for all Buddhists and, in some cases, for all religions,” says McDaniel. “Up until the last 100 years, this hasn’t been the case in Buddhism. Such ecumenical places are a new phenomenon.”

McDaniel’s way into his topic is through the visionaries—lay and ordained—who designed them. Among them are renowned architect Kenzō Tange, who designed a park honoring Buddha’s birthplace in Lumbini, Nepal; designers Braphai and Lek Wiriyaphan, spouses who created three massive Buddhist historical and amusement parks in Thailand; and monk Shi Fa Zhao, founder of a multipurpose temple in Singapore. Other visionaries make an appearance, including Đinh Văn Vui, the developer of Suối Tiên, widely known as “king of the Vietnam entertainment industry.”

Examinations of architects and projects support McDaniel’s third and final argument: great visions and visionaries are shaped and shifted by unforeseen circumstances.

“I call this ‘local optima,’” McDaniel explains. “When studying architects we can’t just look at the plans and dreams of a single person, we have to look at all the factors that go into developing, building, and maintaining a site—such as weather, economics, community input, and visitor interaction.”

As an example, Tange’s Lumbini project has been a “complete failure.” Still under construction more than 30 years after groundbreaking, it’s the victim of an undesirable location, local corruption, political maneuvering, and other elements outside of the architect’s control. Tange himself gave up on it in 1985.

In Singapore, Shi Fa Zhao’s Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum is more successful, if not exactly what the abbot envisioned. “The space is a cultural, community, and film center, vegetarian restaurant, ancestor shrine, museum, pleasure garden, and reliquary all in one,” McDaniel says. “Shi Fa Zhao’s original idea was for a community center that wasn’t for religious practice. But neighbors wanted to use the space for their Buddhist rituals. So local demand and need transformed Shi Fa Zhao’s original idea and ideals for the temple—and today the site is thriving.”

Putting it all together, in end, McDaniel says, “These spectacles—and their success or failure—are about much more than just display, but about how that display is received and interacted with.”