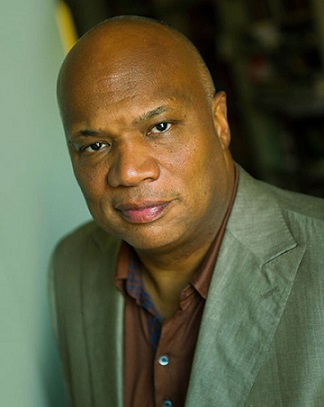

While preparing to teach a graduate course, Michael Hanchard happened upon an obscure citation of a series of lectures entitled “Comparative Politics.” It became the impetus for his forthcoming book The Spectre of Race in Comparative Politics, which seeks to shine a light on the role of racial hierarchy in modern politics. Hanchard, a recently appointed professor of Africana studies, is a political scientist who specializes in nationalism, racism, and transnational black politics. Hanchard is the author of multiple books, including Orpheus and Power: Afro-Brazilian Social Movements in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, Brazil, 1945–1988 and Party/Politics: Horizons in Black Political Thought.

The “Comparative Politics” lectures were given by a historian named Edward Augustus Freeman, one of the founding members of the history department at Oxford University. Though examples of comparative politics in literature and thought can be traced back to Aristotle, Freeman was attempting to define and elevate the field into a science for inquiry into modern politics. In Freeman’s view, racial hierarchy and the study of modern politics were one and the same. “He saw himself as creating this new scientific discipline centered on the comparative study of political institutions, which in his mind would prove the political supremacy of Euro-Aryans,” says Hanchard.

In 1882, Freeman was a visiting professor at Johns Hopkins University. Hanchard found that Freeman’s writings and lectures had a significant impact on the Seminary of Historical and Political Science founded by historian Herbert Baxter Adams, which greatly influenced the graduate students and faculty there, including a Ph.D. student who turned out to be none other than Woodrow Wilson, future 28th president of the United States.

Wilson, along with other statespeople and political thinkers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, devised what Hanchard refers to as racial regimes: the formal and informal institutions that operate to deny political rights to specific populations, even in some of the most robust democratic places in the world, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

Hanchard says that Woodrow Wilson’s political legacy, ranging from the League of Nations to the re-segregation of the U.S. civil service, resembles certain features of British and French domestic and foreign policy. “These are populations that have been institutionally segregated through disproportionately higher levels of unemployment, high levels of under-education, and lack of opportunity. It’s the result of policy, not just idiosyncratic practices.”

The Spectre of Race in Comparative Politics traces examples of discriminatory citizenship regimes all the way back to ancient Athens, often seen as the birthplace of many democratic systems. Pericles’s Citizenship Law 451 was an attempt to base citizenship on bloodlines and descent in order to limit the possibility that Athenians could be enslaved, thus defining who had rights and who was forced to the margins.

Focusing on the contradictions between democratic institutions and practices and anti-democratic institutions and practices within the same society is key to understanding the dynamics, Hanchard says. “The question becomes, what are the mechanisms that turn people into citizens and what are the mechanisms that either limit or prohibit citizenship for every member of a society?”

In order to bolster discussion around these complex issues, Hanchard is spearheading the Marginalized Populations Project within Africana studies. The initiative aims to examine Afro-descendant populations in a comparative perspective, including Afro-Latin populations, scheduled castes in India, and black populations in the United States and the African continent—all examples of populations who experience the denial of political rights. Hanchard hopes to put together a working group, a workshop, and an international conference at Penn over the next two years.