Passion, Persistence, and Payoff

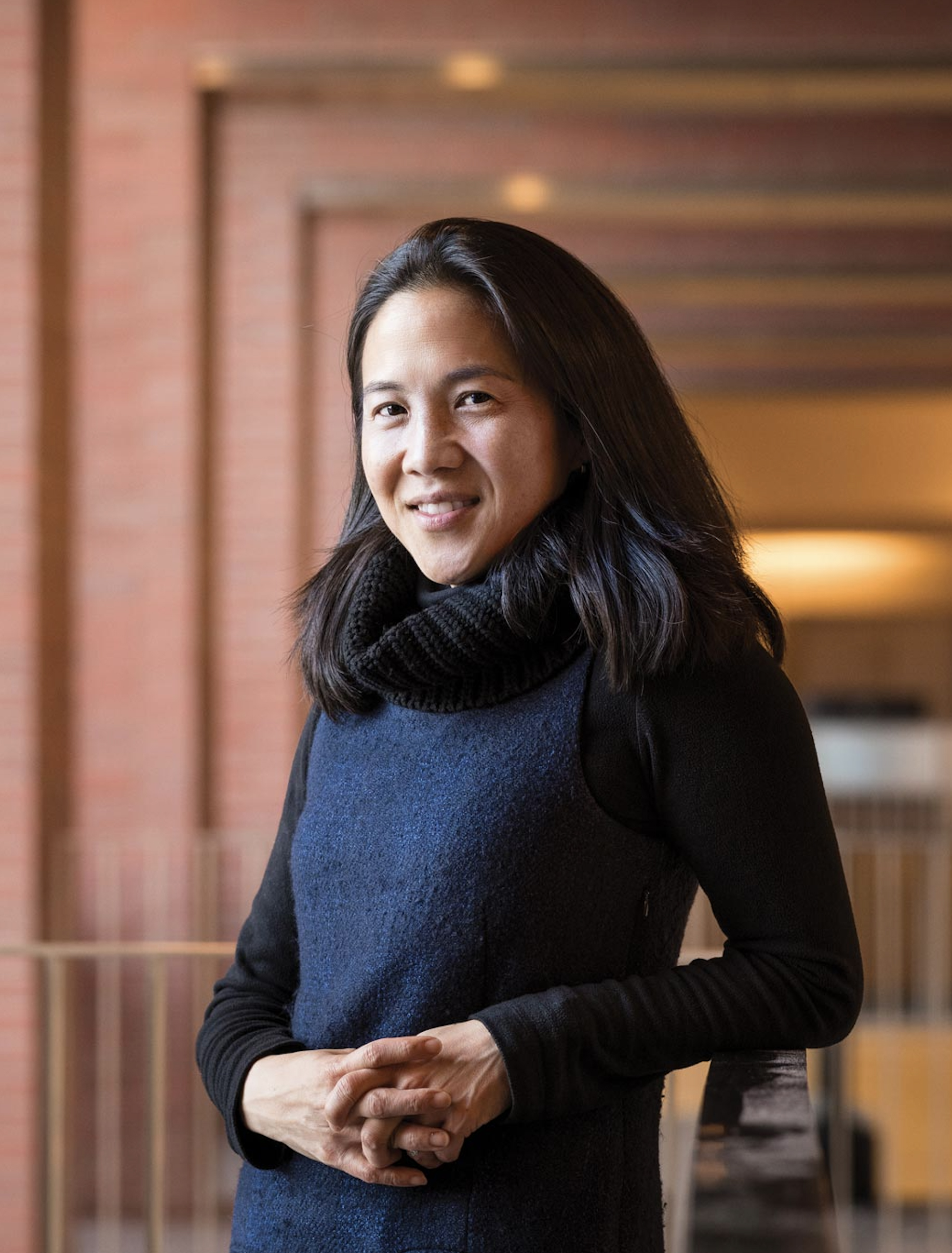

Angela Duckworth, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Psychology, explores why perseverance matters.

Psychologist Angela Duckworth knows grit—and people want to know what she knows. Her book on the character trait spent more than 20 weeks on The New York Times Best Sellers list. She has shared insights on the matter with the White House, the World Bank, NBA and NFL teams, Fortune 500 CEOs, and school districts across the country. Some 13 million people have watched her TED Talk, making it one of the most viewed ever.

Over the past 10 years, Duckworth’s research on grit, which she defines as passion and perseverance for long-term goals, has become a touchstone for teachers, parents, coaches, employers, and others who encourage and cultivate success.

If Duckworth’s professional life centers around understanding character traits like stick-to-itiveness, was there a moment in her personal life when she remembers first persevering for a passion—when she recognized her own grit?

“This is certainly a question I've reflected on, given what I do for a living,” says Duckworth, Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor of Psychology. “I have always felt very motivated by public service. I remember feeling in college a tremendous sense of conviction and determination for public service. It’s really what motivates me.”

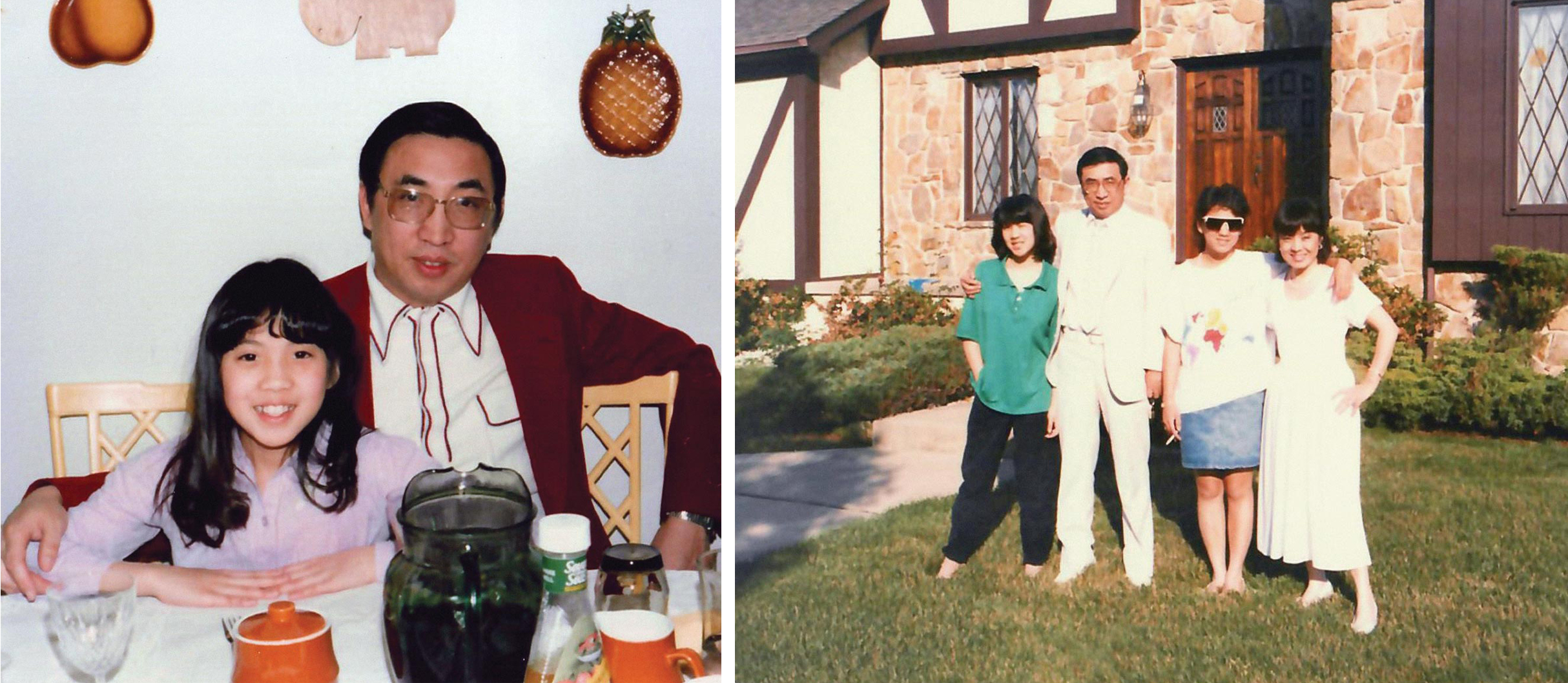

Duckworth’s earliest lasting act of public service was as a Harvard undergrad. “I was acutely aware that the school’s verdant campus was a stone’s throw away from persistently poor communities,” she says. “I felt sad for all of the bright kids whose lives were not headed in a direction they were worthy of or deserved.”

This striking contrast between opportunity and disenfranchisement inspired Duckworth to start a nonprofit enrichment program for kids in Cambridge. She raised money, secured a facility, hired staff, recruited students, and incorporated, all while barreling toward the end of senior year. The program, Breakthrough Greater Boston, opened two weeks after she graduated and remains open today. Duckworth would run it for two years before heading to Oxford University on a Marshall Scholarship to earn a Master of Science in neuroscience.

Following Oxford, she worked in a series of intense environments such as McKinsey and Philadelphia, New York City, and San Francisco public schools.

While teaching, Duckworth observed that her highest-achieving students weren’t always the smartest or most talented and her smartest students weren’t always high achievers. What successful students had in common was self-control, stamina, and commitment to hard work.

Intrigued by the phenomenon, she applied to Penn’s doctoral program in psychology to investigate it, expressing in her application a distinctive view of education.

“Learning is fun, exhilarating and gratifying—but it is also often daunting, exhausting, and sometimes discouraging. To help chronically low-performing but intelligent students, educators and parents must first recognize that character is at least as important as intellect.”

At Penn, Duckworth studied with positive psychology movement pioneer Martin Seligman, Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology and Director of the Positive Psychology Center, building a body of research on the relationship between character—particularly grit and self-control—and achievement. Her work reverberated among educators and school reformers eager to find a measurable approach to helping kids across the socioeconomic spectrum succeed.

In 2013, by then a faculty member in the Department of Psychology, Duckworth was recognized as a MacArthur Fellow. Known as the “genius” grant, the fellowship acknowledges professional, artistic and intellectual ingenuity, across a range of fields. Duckworth received the grant for transforming common understandings of the roles that grit and self-control play in educational achievement.

The same year, as Duckworth’s research on grit gained traction nationwide, she established the Character Lab, a nonprofit that studies and creates new ways of cultivating character. The Lab pursues initiatives to help one million or more middle- and high-school students improve an aspect of their character.

Located near Penn, the Lab’s 16-person team of researchers, educators, and product, design, and communication specialists—an extra supportive team member is the “Lab’s Best Friend,” a rescue dog belonging to one of the staff—takes a twofold approach to cultivating character.

First are Playbooks that help teachers translate character development research into classroom practice. Featuring ready-to-use videos, lesson plans, and worksheets, the resources target specific character traits: curiosity, grit, gratitude, self-control, purpose, growth-mindset, and zest. The Lab’s second priority is making character development field research “fast, frictionless, and fruitful.”

“We’ve learned the hard way that it takes at least a full year for a scientist to begin collecting data for a single school-based research study,” says Duckworth in the Lab’s 2017 Annual Letter. “Researchers first have to find and develop a relationship with school partners, then obtain written parental consent and approval from university research institutional review boards in order to access identifiable student data, next arrange to administer study protocols during school hours, and finally secure report card grades and other data from schools.”

The growing Character Lab Research Network of scientists and schools hopes to solve this problem. The web-based network facilitates rapid prototyping, longitudinal studies, and high-powered, pre-registered, randomized controlled trials of character development research.

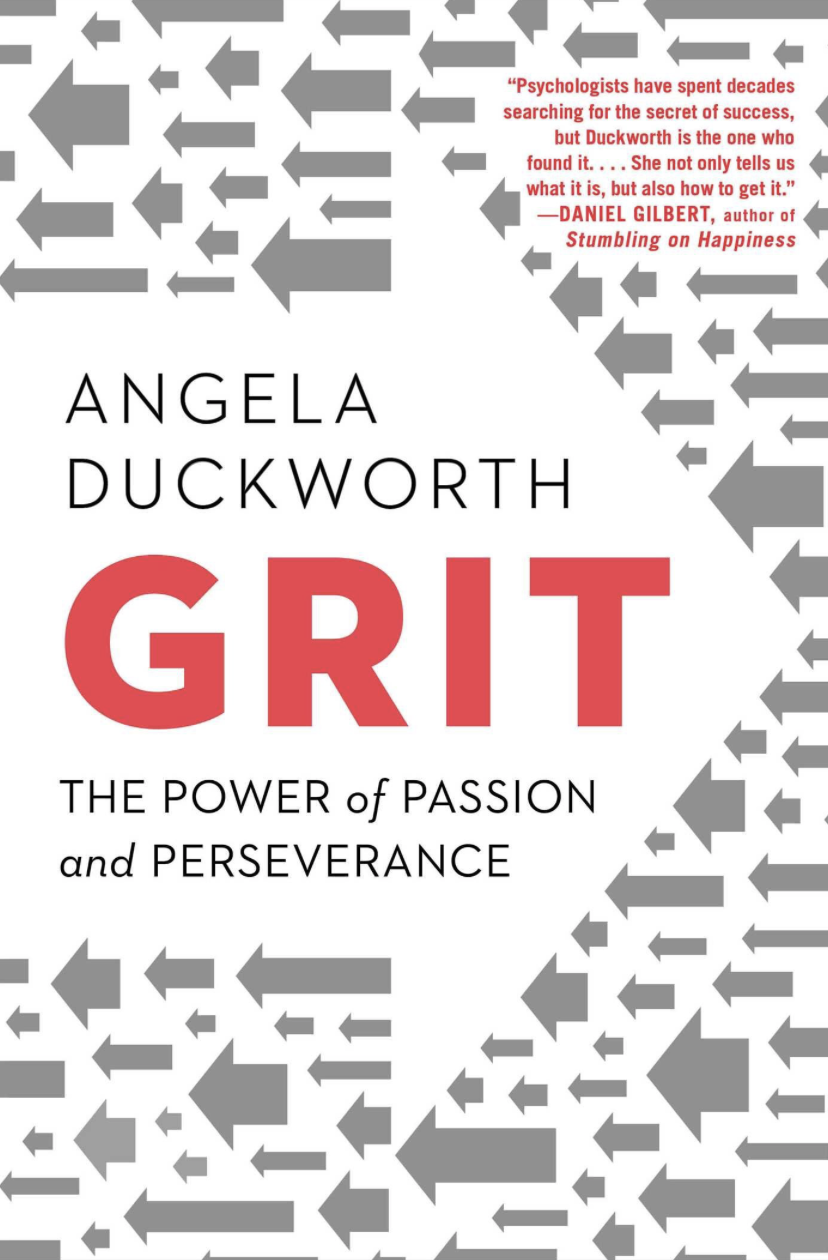

In 2016, Duckworth published her first book, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. It catapulted her to the mainstream. She became a highly sought-after consultant or speaker for school districts and determined places like Google, Adobe, and the Seattle Seahawks. And a multitude of media outlets, among them NPR, The New York Times, Elle, HuffPost, Marie Claire, Forbes, and PBS News Hour, have cited the book.

A #1 New York Times best seller, the book draws on lessons from history, literature, and interviews with high-profile people to explore why effort counts twice toward goals; how to trigger lifelong passion for an activity; if warm embraces or high standards are better for children; and whether grit can be learned.

Today, Duckworth is widening the aperture on character to look at behavior overall. With Wharton’s Katherine Milkman, Evan C Thompson Endowed Term Chair for Excellence in Teaching and Associate Professor of Operations, Information, and Decisions, she has launched Behavior Change for Good (BCFG), a new initiative ambitiously described as “the greatest interdisciplinary effort in history to solve the problem of enduring behavior change” (see sidebar on p. 30).

“The project's goal is to answer the riddle of how to get people to do things that are in their best interest,” Duckworth explains. “This is true across all the domains of life, from taking care of your health to studying and learning to manage money.”

Behind the initiative is Duckworth’s “dream team” of behavioral scientists, including two Nobel Laureates, three MacArthur Fellows, and two members of the National Academy of Sciences.

The group is designing behavioral interventions in three focus areas: health, education, and personal finance.

“The challenge in these domains is that everyone really does know what's good for them, but it's very hard to make the consistent, small choices that create change for good,” says Duckworth. “It’s an age-old worry, but we feel like we have a chance of really figuring things out because we have two things unavailable to ancient philosophers and theologians: technology and the modern science of behavior change.”

The initiative will work with partners, including national health care organizations, school districts and education providers, banks, and fitness chains, to digitally deliver behavior change programs to customers and students. The programs are designed by BCFG team scientists.

“Both Angela and I see behavior change as the most important problem of our time,” says Milkman. “And it’s one that we can make major steps toward solving.”

The genesis of BCFG was a University-wide call for projects for 100&Change, a MacArthur Foundation competition for a $100 million grant to solve a single, critical world problem. Duckworth, Milkman, and colleagues drafted a proposal they argued could help with the challenge of “enduring behavior change.”

“I saw the email announcing the eight 100&Change finalists before Angela did, so I called her to share the news that we weren’t in the set,” Milkman recalls. “The first thing she said when I told her we hadn’t made the final eight was: ‘What!?!? That’s crazy!’ The second thing she said was ‘Well, obviously, we’re doing this anyway!’ Now that’s grit!”

And they did. The University and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative have provided funding for an initial three years, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has given early support. (Anyone interested in following the initiative’s progress can tune in to the Freakonomics Radio podcast archive. The podcast, a big fan of Duckworth’s research, has been reporting on BCFG since it was in the running for 100&Change.)

The BCFG team is already testing two behavior change programs. In the StepUp Program, the researchers are working with 24 Hour Fitness, one of the largest national gym chains, to monitor the frequency of gym visits. The scientists are aiming for hundreds of thousands of data points.

The LevelUp Program, conducted in partnership with the Character Lab Research Network, involves tens of thousands of high school students doing different activities to see which boost their grades the most.

In the meantime, as the work of changing behavior goes on around the country, Duckworth is maintaining a regular teaching schedule. She leads the master’s degree course Research Methods and Statistics and advises undergrads completing their research requirements. And this fall, she and Milkman are co-teaching an undergraduate seminar on behavior change.

“Before I became a psychologist, when I was teaching younger students, I knew I would work on behalf of kids for the rest of my life,” remembers Duckworth. Her work for young people has been, by the accounts of many parents, teachers, academics, and students, revolutionary. And as she now tackles the next frontier of behavioral psychology—making life-altering behavior change possible—her work has clearly only just begun.

Changing Behavior for the Better, Forever

Every day in the U.S., smoking, unhealthy eating, lack of exercise, alcohol consumption, and other changeable behaviors cause 40 percent of premature deaths. One in three families has no retirement savings. And half of college students drop out before earning a degree. The Behavior Change for Good Initiative (BCFG) believes behavioral science has the potential to radically change these outcomes.

BCFG unites dozens of leaders in the social sciences, business, medicine, computer science, and neuroscience across top research universities to help improve people’s daily decisions about health, education, and savings.

Using a digital platform and client relations infrastructure built and operated by Penn, the team will seamlessly incorporate the latest insights from their research into massive random-assignment experiments. The unprecedented sample sizes and speed with which BCFG can run dozens of studies at once represents a paradigm shift in social science research.

BCFG’s research team partners with some of the world’s leading companies and nonprofits to help change for the good behaviors of the partners’ customers, students, or members.