OMNIA Q&A: What's Good?

Ahead of the series finale of NBC's The Good Place, Errol Lord, Associate Professor of Philosophy, weighs in on how to be a good person and how the show might end.

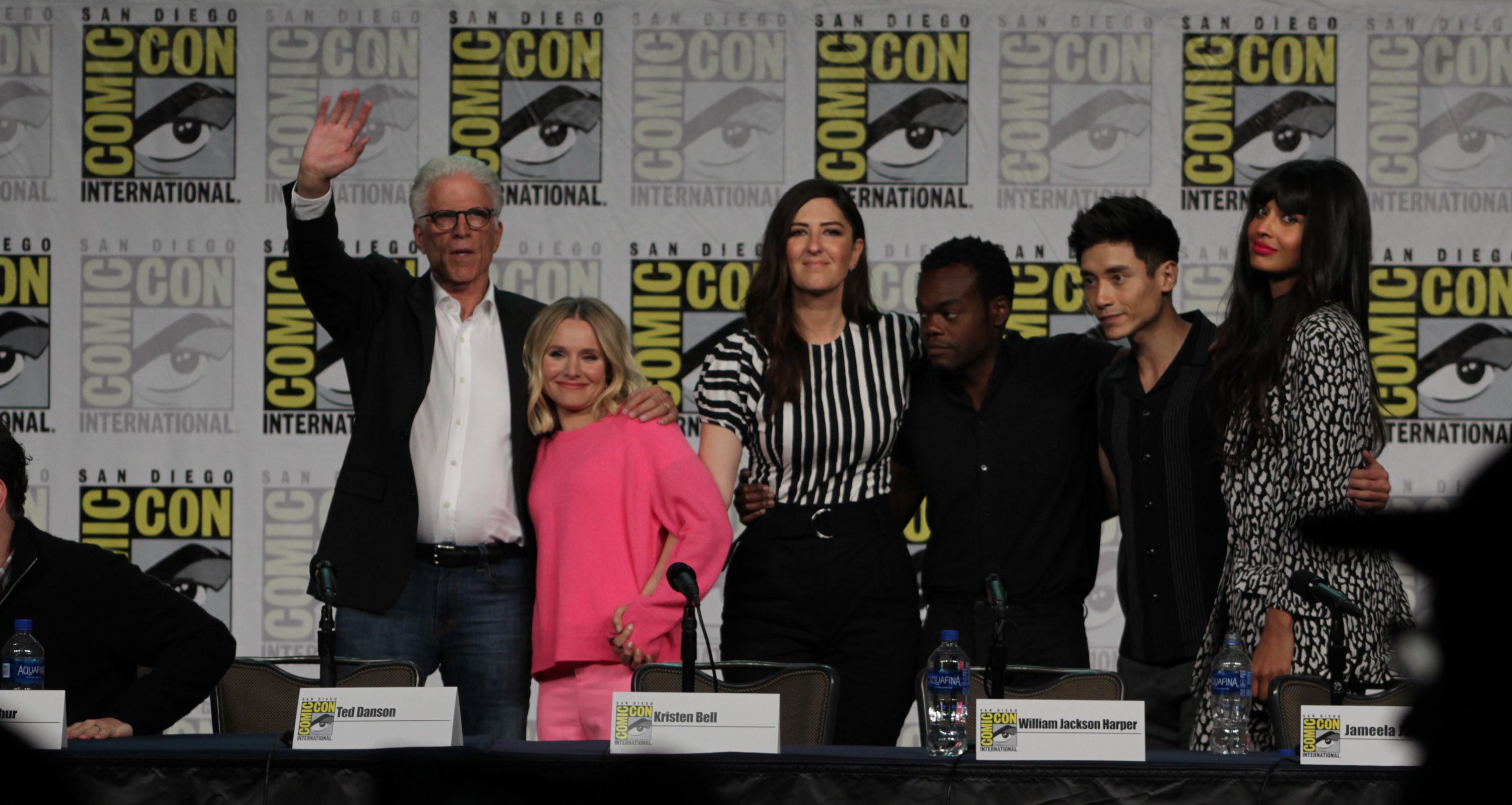

Parts of NBC’s The Good Place could be from any other multi-camera sitcom: It’s 22 minutes long, stars TV vets Kristen Bell (Vernonia Mars) and Ted Danson (Cheers, Curb Your Enthusiasm), and is heavy on pop culture references. But no other sitcom takes place in the afterlife and features debates over the relative values of utilitarianism and deontological ethics. No other sitcom has philosophy professors deliver lectures to the writers’ room, or uses the joke, “That’s why everybody hates moral philosophy professors!” as a running gag.

If you haven’t seen The Good Place, here’s a cheat sheet: Eleanor (Bell), Chidi (William Harper Jackson), Tahani (Jameela Jamil), and Jason (Manny Jacinto) have died and gone to the titular “Good Place,” a secular version of heaven dotted with frozen yogurt shops and overseen by Michael (Danson), an angel figure, and Janet (D’Arcy Carden), an all-knowing helper who’s not-quite-human and not-quite-robot. But things aren’t as peaceful as they should be: Eleanor and Jason are self-proclaimed dirtbags who know they didn’t earn their way to an eternal reward and fear being found out, Tahani is an insecure socialite driven to one-up her peers even as she thinks she’s in heaven, and the perpetually indecisive philosophy professor Chidi is stymied by one moral dilemma after another. After a season of hijinks (spoiler alert), Eleanor correctly guesses they are in the Bad Place, and with a maniacal laugh, Michael reveals himself to be a demon who is psychologically torturing them. With a snap of his fingers, he reboots them to wipe their memories and start their torment anew.

After four seasons and 802 reboots, Michael, the humans, and an evolved, more-human Janet are on the same side, fighting the demons of the Bad Place and demanding an improved, less punitive system for deciding who is good or bad. Eleanor, now in a reboot-spanning relationship with Chidi, has emerged as the leader as they work to convince a powerful judge (Maya Rudolph) to reconsider not only the fate of their group, but of humanity as a whole.

In the lead up to The Good Place finale, we spoke to Errol Lord, Associate Professor of Philosophy, about what it means to be good and what the show gets right about philosophy.

Q: Does everyone really hate moral philosophy professors?

I would say no, but I think that the joke still gets at something that's true about philosophy professors and the danger of being consumed by theory. Chidi is a moral philosophy professor who is paralyzed by the thought that he can solve problems by drawing distinctions. I would say most moral philosophy professors aren't like Chidi, because there's a real way in which their lives don't reflect their theories.

To illustrate, consider the consequentialist theory says that morality requires you to perform actions that produce the most good. Peter Singer, probably the most famous living philosopher, has been pushing the consequentialist view for a long time. In his heart of hearts, he thinks that people are required to help people to the point where they would be worse off than the people they are helping. He means, in his heart of hearts, that we should give to the point of near-death.

For most people, if they attempted to live by that theory, they’d deplete themselves monetarily and psychologically. So, some consequentialists say you shouldn’t live by the theory, because in the end, you wouldn’t produce the most good.

Q: How does philosophy define what is good? Can it?

Every single thing about this is controversial. A popular view with consequentialists has been that pleasure or happiness is the good and pain or unhappiness is the bad, so we should maximize happiness. But most of the time, it's not possible to increase everybody's pleasure. This is illustrated by the Trolley Problem, a philosophical exercise that plays out on the show. If you’re driving a trolley and you can steer it to kill one person, or steer it to kill five people, what do you do? The consequentialist theory says you kill one person to save five people, but that is hard to swallow, especially when you scale up.

Different theories have radically different views on what it means to be a good person. On The Good Place, the theory that ends up dominating is virtue ethics: To be a good person, you must be virtuous, which is to be brave, kind, just etc. The show also promotes contractualism, the idea that morality requires you to act in a way that you can justify to other people. This is an idea from T.M. Scanlon’s What We Owe Each Other, published in 1998, and it goes back to Thomas Hobbes’ 17th-century ideas about the social contract.

Q: How do philosophical theories play out on The Good Place?

The creator of the show, Mike Schur, has said that he initially based the show on the consequentialist point of view. The characters earn points based on the effects their actions have on others. As the show went in a more virtue theoretic direction, it’s less about consequences and more about a person’s character. Virtue theory places an emphasis on the traits from which you act. This gives rise to a puzzle about whether you can really try to be a good person since that looks like the wrong motivation. This puzzle is central to the show.

There’s a tension in the show as the characters try to work out different theories. And that’s the experience of being a philosopher: realizing that there are puzzles and tensions between plausible ways of thinking. We all have ideas about moral philosophy or the right way to live, but they don’t always fit together.

Q: Who is “good” on The Good Place?

At the start of the show, Eleanor is selfish and uninterested in others, while Chidi is reflective and concerned about how he affects everything around him. But by season four, it’s obvious that Eleanor has improved more than Chidi. Chidi’s character exposes some limitations of moral philosophy and makes vivid that thinking about things only through theory is not a good idea.

Nevertheless, Eleanor’s interactions with philosophy were important to her development. They directed her attention towards things that were important. And Chidi learns from Eleanor that it’s crucial to focus on the particularities of your concrete world. So, they both brought something to the table, a sort of forging of theory and practice.

Q: If you were in the The Good Place, what philosophers would you want to debate with over frozen yogurt or stardust milkshakes?

Kant. Bernard Williams. Plato and Aristotle. It would be fun to have Derek Parfit and T.M. Scanlon—but Scanlon is still alive so I don’t want to jinx it. Each of these philosophers wrestled with whether there was some cosmic meaning to the universe and whether this was needed in some way.

And then, Iris Murdoch and Phillipa Foot. Murdoch primarily for her rightful insistence that we pay attention to all of life's messy details; Foot primarily because her sort of neo-Aristotelian is a view that I am attracted to. The pair because they were great friends and I'd love to be able to talk to them together.

Q: Jason and Eleanor make digs about their home states of Florida and Arizona, with Eleanor frequently calling herself an “Arizona trashbag.” As an Arizona native, do you care to comment?

I was at a conference in Arizona this month, and I told my colleagues that The Good Place really gets the state. It's one thing to go for the easy Florida jokes; it's more of an achievement to accurately portray the silliness of Arizona.

Q: Do you have any predictions for how The Good Place will end?

In a sense, the deepest question in moral philosophy is, is there significance to human life? The Good Place isn’t really about these four humans. It’s about whether there is this type of meaning. It looks like the show ultimately will take a stand on this question.

In the most recent episode, we learn what the Good Place is like. At first it is just as the characters imagined it—perfect. But then we learn all is not well. Getting what you want for eternity turns out not great. They decide immortality is not what it’s cracked up to be. Meaning depends on mortality. So, where will they go from there—what will the final twist look like?