No Man’s Land

The Continued Long-Term Consequences of Mass Incarceration in the United States

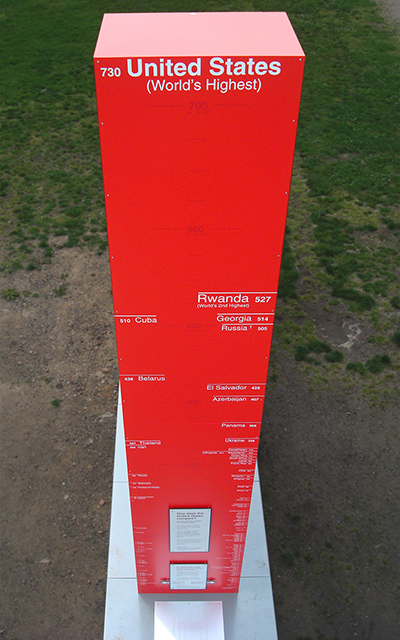

Over the past 40 years, the U.S. has come to account for a disproportionate amount of the international prison population: Though Americans make up less than 5 percent of the world’s people, they account for almost 25 percent of the incarcerated. Pressure for reform mounts, supported by prominent political figures from both sides of the aisle and influential thought leaders, including Pope Francis, who met with inmates at a Philadelphia prison during his September trip to the States, and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who used an October visit to a California prison to issue a call to action on the social media platform that reaches nearly 1.5 billion active users monthly. Here, experts from a range of fields share their thoughts on this hot-button issue that is becoming more and more a part of the public discourse.

We Are the Carceral State

By Marie Gottschalk

Fifteen years ago, mass imprisonment was largely an invisible issue in the United States. Since then, criticism of the country’s extraordinary incarceration rate has become widespread across the political spectrum. But reforms to reduce the number of people in jail and prison have been remarkably modest so far.;

Meanwhile, a tenacious carceral state has sprouted in the shadows of mass imprisonment and has been extending its reach far beyond the prison gate. It includes not only the country’s vast archipelago of jails and prisons but also the far-reaching and growing range of penal punishments and controls that lie in the never-never land between the prison gate and full citizenship. As it sunders families and communities and radically reworks conceptions of democracy, rights, and citizenship, the carceral state poses a formidable political and social challenge.

The reach of the carceral state today is breathtaking. More than 8 million people in the United States—or in 1 in 23 adults—are under some form of state control, including jail, prison, probation, parole, community sanctions, drug courts, and immigrant detention. Millions more are booked into jail each year. An estimated 70 million to 100 million people—or as many as one in three Americans—has a criminal record. Millions of people have been condemned to “civil death,” denied core civil liberties and social benefits because of a criminal conviction.

The carceral state directly shapes, and in some cases deforms, the lives of tens of millions of people who have never served a day behind bars or been arrested. Many neighborhoods and communities have been depopulated and upended as swaths of young men and women have been sent away to prison during what should be the prime of their lives. An estimated one in four black children will experience having an imprisoned parent by the time they turn 14 years of age.

The problem of the carceral state is no longer confined to the prison cell and prison yard and to poor urban communities and minority groups—if it ever was. The U.S. penal system has grown so extensive that it has begun to metastasize. It has altered how key governing institutions and public services and benefits operate, everything from elections to schools to public housing. The carceral state also has begun to distort essential demographic, political, and socioeconomic databases, leading to misleading findings about trends in vital areas like economic growth, voter turnout, unemployment, poverty, and public health. The carceral state has been radically remaking conceptions of citizenship as it creates a large and permanent group of political, economic, and social outcasts. In short, there are not six degrees of separation from the carceral state for anyone living in the U.S. today.

The key challenge to razing the carceral state is not figuring out the specific sentencing and other reforms that would slash the number of people in jail and prison. It is figuring out how to create a political environment that is more receptive to such reforms and how to make the far-reaching consequences of the carceral state into a leading political and public policy issue.

Over the past decade or so, the growing opposition to mass incarceration has tended to gravitate toward two different poles, both of them inadequate in the face of these challenges. One pole identifies racial disparities, racial discrimination, and institutional racism as the front lines in the challenge to the carceral state. The other is anchored in how the fiscal burden of the vast penal system is increasingly untenable in an era of tight government budgets.

The new Jim Crow and the fiscal imperative frames have made major contributions to our understanding of the carceral state and have pried open some important political space to challenge it. But they also have contributed to public misperceptions about the relationship between crime and punishment and about who is being sent to prison and why. This has fostered some misguided penal reform efforts. These two frames are unlikely to germinate and sustain the broad political movement necessary to slash the number of people under direct state supervision and ameliorate the many ways in which the carceral state has deformed U.S. society and political institutions.

Marie Gottschalk, Professor of Political Science, served on the National Academy of Sciences Committee on the Causes and Consequences of High Rates of Incarceration. Her research focuses on criminal justice, health policy, race, the development of the welfare state, and business-labor relations. Her latest book is Caught: The Prison State and the Lockdown of American Politics.

Real Reform and Mass Incarceration

By Jason Schnittker

The tide is turning on mass incarceration. After decades of growth, the size of the prison population is declining in some states. Across the political spectrum there is more interest in further reductions. This effort is motivated by a number of things, including concerns about the costs of housing inmates, a recognition of racial disparities in arrest and incarceration, a progressive interest in providing more opportunities to the disadvantaged, and a libertarian concern over government overreach. It’s little wonder that political figures as diverse as Rand Paul, Barack Obama, and Grover Norquist have endorsed criminal justice reform of one form or another.

But don’t take this political foment as a harbinger of an easy reversal. The reach of the criminal justice system in the lives of the disadvantaged is deeper than we often appreciate. A considerable body of research shows the lasting harm of a prison record for employment opportunities, family life, and health. But it is not entirely clear whether incarceration per se is the entire issue. The mark of a criminal record itself is an important driving force in the long-term negative effects of incarceration, and eliminating that mark is difficult. Even if we find good substitutes for incarceration, like home detention or diversion programs, it is not clear these things will make it easier for those who must still grapple with a criminal record when they, for example, apply for a job. By the same token, incarceration has negative consequences for mental health, but much of this association is driven by the discrimination former inmates face. Eliminating a prison sentence does very little to eliminate the stain other people will see in a conviction.

If politicians are concerned with providing offenders with more opportunities to make things right, rolling back the prison system is just a start. This is where it gets tough. No one would argue that the guilty should not be punished in some way. And some offenders surely deserve a prison sentence. Society demands and requires a robust criminal justice system. But at present the power of a criminal record far exceeds its usefulness. Providing former inmates with more opportunities involves thinking about the situation broadly. It involves, for instance, thinking of the prison system as an opportunity for training rather than a warehouse. It involves thinking about programs to provide inmates with health services, including crucial mental health services, when they’re released. And it involves encouraging employers to hire those with a criminal record, in some cases with real assurance that the risk they’re assuming will pay off. Bridging efforts of this sort have been shown to be highly effective.

Indeed, if we want to reduce the impact of the criminal justice system in the lives of the disadvantaged, there’s an argument for moving beyond even the offender. Some evidence suggests that merely the threat of arrest and the strong presence of a police force in a neighborhood can undermine the well-being of residents. When we talk about criminal justice reform, we usually talk about offenders, but many people are touched by the criminal justice system’s expanding net.

Prison reform is happening already. Efforts are occurring locally, in states, and at the federal level. These efforts will expand and the size of the prison population is likely to go down even more. But we need to think seriously about what the real goal is. It might be easy to reduce the size of the prison system. In some ways, this is simply an operational issue: if fewer people are coming in than going out, the prison population will shrink. But it will require even more political will and imagination to remove the scar left by 40 years of expanding the criminal justice system.

Professor of Sociology Jason Schnittker’s research focuses on the social, biological, cultural, and institutional determinants of health.

The Solution to Mass Incarceration is Algebra

By John MacDonald

As of 2014 roughly 1.6 million U.S. adults are serving time in a state or federal prison. This compares to roughly 300,000 in 1978. This five-fold increase in the size of the U.S. prison reflects a relatively new era of mass incarceration. Many advocates for ending mass incarceration erroneously think that state and federal drug laws are the primary source for why we have sky-high rates of imprisonment, but changes in these laws have played a minor role in the increase in prison rates in the U.S. The main drivers of mass incarceration have been an increase in the number of offenses that receive mandatory prison time, an expansion in the number of prison-eligible offenses, and state and federal sentencing laws that require individuals convicted of violent offenses to serve a substantial portion of their sentence before being granted release.

These three factors have mechanically increased the size of the prison population. One can express this as a simple formula where the current state of mass incarceration (m) equals the average certainty (c) of imprisonment plus (+) the average length (l) of stay in prison.

By increasing the number of crimes eligible for prison, prosecutors have free rein to charge people with multiple duplicative crimes and offer them not-so-stellar “deals” in which defendants end up serving substantially longer prison sentences than they would have in the past. Take a concrete example: An offender who committed a robbery in 1978 may have faced a single felony charge of robbery. If that offender was convicted he or she would have received a prison sentence of 10 years, but—with good behavior while in prison—could expect to be released in three years (two days off for every three good days).

That same offense in 2010 would likely face three charges: robbery, use of a handgun in commission of a felony, and felony menacing. In the plea bargain a prosecutor’s offer takes two charges off, removing the handgun and menacing charge. The defendant is now is convicted of a robbery offense, but in 2010 can expect to spend eight years in prison since states no longer grant such generous “good time credits.” Under the more current scenario an accused offender is also more likely to accept a plea bargain that would have been rejected in the 1970s as a bad deal. After all, in the 1978 case the defendant charged with felony robbery may have been only willing to accept a plea bargain for an aggravated assault conviction, where he or she would receive only one year in prison.

In recent years there has been some leveling off in imprisonment rates, largely due to policy efforts made in a number of states to divert drug and nonviolent offenders from state prisons or to reduce prison populations in response to court orders. These changes will not reverse the size of the prison population. In order to make a major dent in prison populations, state and federal legislatures need to make adjustments to the basic algebra of mass incarceration.

A first step could be some serious reconciliation of state and federal criminal codes. Reducing the number of duplicative offenses in state and federal criminal codes that are prison-eligible would be important. If two crimes are essentially the same and have similar recommended sentences, then leave only one on the books. Relatedly, legislatures could require that new laws proposed to be prison-eligible have to replace existing law—no duplications allowed.

A second step would be to expand access to good time credits for early release from prison. Letting older convictions only count toward mandatory sentences if they have occurred within the past five years would be a good starting point. If more than five years have passed since someone’s last related conviction, do we need to count that against their current conviction at sentencing?

These two steps require serious political will. However, they don’t require that legislatures agree on the normative reasons behind sending someone to prison. They simply require legislatures to agree that we should treat prison sentences with some degree of austerity. This means reducing the number of prison-eligible offenses (c) and the average length of stay (l), without reducing the overall chance that serious offenders will receive sufficient prison time for their offenses.

John MacDonald is professor and chair of criminology. He also serves as the Penny and Robert A. Fox Faculty Director of the Fels Institute. His research focuses on primarily on the study of crime and violence, race and ethnic disparities in criminal justice, and the effect of public policy responses on crime.

Mass Incarceration and the Life-Course

By Charles Loeffler

Incarceration has existed since at least Ancient Greece. However, its use as a punishment instead of as a form of pretrial detention crystalized in the 19th century when the use of corporal punishment declined throughout the western world and legal authorities sought alternative means of sanctioning criminal behavior. One remnant of this new form of incarceration can be seen in the Eastern State Penitentiary, located in the Fairmount section of Philadelphia, where prisoners were originally kept in solitary confinement for the duration of their sentences to encourage repentance and reform.

Despite some disastrous results and early studies showing that virtually no prisoners were reformed, the use of prison as punishment continued. However, policymakers in the early 20th century began experimenting with more humane prison conditions, rehabilitative programming, and early parole releases.

This equilibrium began to change in the 1970s as rising crime rates coincided with a growing disillusionment with the criminal justice system, leading policymakers to ratchet up the use of incarceration. Through a series of legislative and other policy decisions, more people would be incarcerated, more often, for more time than at any point in U.S. history. Between 1970 and 2000, the number of persons in prison would jump from roughly 200,000 per year to over 1.4 million.

For scholars and policymakers, the consequences of this development have been quite complicated. While the scale of imprisonment has contributed to the record declines in crime, the toll that this unprecedented social experiment has had on human lives is cause for concern. If imprisonment has left ex-prisoners even less able to contribute productively to society than before they were incarcerated, then society will have gained less in the long run at substantial expense. However, determining the effects of imprisonment on the life-course (e.g., re-offending, employment, and education) is complicated by the need to observe what would have happened to the lives of the imprisoned if they had been sentenced to community supervision in lieu of imprisonment.

To overcome this challenge, I and others have examined a commonly occurring but often ignored natural experiment wherein criminal cases are randomly assigned to judges with very different patterns of sentencing behavior—some judges sentence most cases to imprisonment while others sentence very few. By tracking thousands of defendants whose cases are assigned to frequently and infrequently imprisoning judges and then checking to see whether they are any more likely to be re-arrested or re-employed five to 10 years after their cases are adjudicated, it is possible to see whether imprisonment—at least for short sentences—has large life-course-altering effects. The results, somewhat surprisingly, suggest that short spells of imprisonment do little to alter the offending and employment trajectories of the imprisoned, at least when compared to similarly situated individuals sentenced instead to community supervision.

This finding raises difficult questions for proponents and opponents of mass incarceration: Imprisonment, despite being incredibly expensive, appears to neither improve nor worsen the lives of the imprisoned. And one hundred years after prisons were first evaluated for their reformative effects, we find ourselves in a similar situation. Prisons can be used as punishment at great expense and doing so may protect the public in the short term, but almost all prisoners are eventually released back into the community and they will likely be no better off for their experience. This leaves us again wondering what else can be done to reduce re-offending and improve other life-course outcomes, not only for the many returning prisoners affected by mass incarceration, but also for the even larger number of non-imprisoned community-supervised persons facing similarly bleak life-course trajectories.

Charles Loeffler is the Jerry Lee Assistant Professor of Criminology. His research focuses on the effects of criminal justice processes on life-course outcomes.