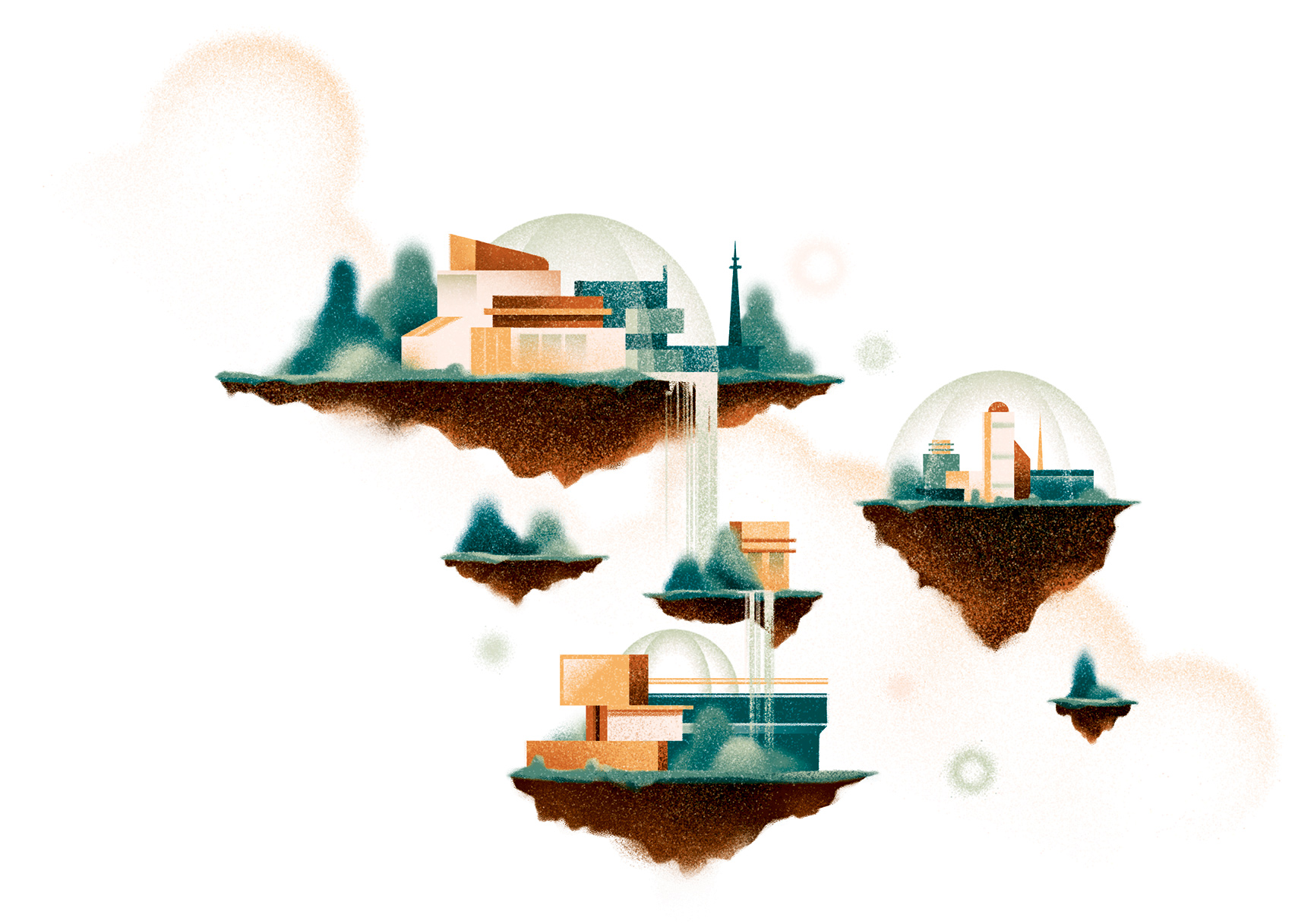

Near-Perfect Communities

In the new book, Everyday Utopia: What 2,000 Years of Wild Experiments Can Teach Us About the Good Life, Kristen Ghodsee, Professor of Russian and East European Studies, explores utopian communities past and present.

Sir Thomas More published Utopia, about an ideal fictional island, in 1516, but the concept of a perfect or near-perfect place existed long before. In the 6th century B.C.E., progressive philosopher Pythagoras—most recognized for his famous triangle theorem—founded a utopian seaside community where the inhabitants lived as equals, shared property, and together considered life’s mysteries, mathematical and otherwise.

Experimental societies like those imagined by Pythagoras, More, and many others make up the crux of Kristen Ghodsee’s new book, Everyday Utopia: What 2,000 Years of Wild Experiments Can Teach Us About the Good Life.

“Utopias can’t be perfectly right,” explains Ghodsee, professor and chair of the Department of Russian and East European Studies. “Utopia always has to be on the horizon, the place that we’re aiming for but are never really going to reach. None of the utopias I explore are perfect, but the point is to keep working toward better and more perfect societies that connect us.”

Ghodsee became intrigued by utopias while on tour for her 2018 book, Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence. The book discusses why capitalism is damaging for women and why socialism, if done correctly, can lead to more economic independence, better work-life balance, and improved personal relationships. Around the world, she would speak to young people intrigued by the tenets of socialism, such as equality, community, and shared property—ideals often shared by utopian communities.

“While I was not suggesting we should replicate the socialist governments of the past, I explained to these young people that there are ways in which certain aspects of socialism could improve all of our lives,” Ghodsee says. “I would consistently hear the same jaded response: ‘It’s great in theory, but it will never work in practice.’ That got me thinking about ways we could apply aspects of utopian socialist ideals and other examples of utopian communities to the present. And then the pandemic hit.”

During that time, Ghodsee dug into examples of experimental bottom-up “utopic” ways of living from around the world, past and present. Unlike her previous book, which focused on more state-driven solutions, Everyday Utopia explores the long history of small, autonomous communities geared toward a more contented and connected society through shared property, child-rearing, and domestic responsibilities, as well as more expansive ideas about who constitutes “family.”

Examples include co-housing communities in Denmark that share chores, matriarchal Colombian ecovillages where residents grow their own food, and laws in Connecticut to grant rights to “alloparents,” people beyond two legal guardians who provide parental-type care to children.

The timing of Ghodsee’s book is apt, she says, because often utopian ideas arise in the aftermath of great political or societal upheaval, like, say, a global pandemic. History provides many examples, including More’s Utopia, written as a veiled criticism of the English government in the wake of the “discovery” of the Americas in 1492. “Plato’s The Republic, which was partly modeled on the Pythagoreans, was published in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War, which completely upended Ancient Greece and ended Athenian democracy,” she adds. “Now, because of the pandemic, we are seeing radical changes to society that would not likely have occurred otherwise, like the acceptance of remote or hybrid work.”

Everyday Utopia is specifically interested in small-scale changes to the private sphere, which sets it apart from other books on the topic. “I’m not writing about universal basic income or shorter work weeks, which are all positive,” Ghodsee says, “but rather about making changes in the way that we live with other people, where we dwell, how we raise and educate our children, how we share or hoard our property, and what constitutes our families.”

Ghodsee notes that in her survey of 2,500 years of utopian experiments in different cultural contexts and across many diverse historical epochs, almost all share a set of values and policies that “bring us together in community with one another.”

In a world beset by increasing inequality, climate change, and housing insecurity, Ghodsee says she hopes that her book can provide examples of a better way forward that will lead to greater contentment and less loneliness. “Without hope, what do we have left?” Ghodsee concludes. “I still believe in the possibilities of the good life.”