Moments in Time

Students from Senior Lecturer in English Paul Hendrickson’s long-form nonfiction master class share powerful passages from their intensely personal projects.

Philosophizing with a club bouncer, comparing wall decorations with the woman who occupied the same campus housing space 35 years prior—these are just a few of the epiphanic moments that grew out of Paul Hendrickson’s Advanced Writing Projects in Long-Form Nonfiction course. For Lily Stein, C’22, Alan Jinich, C’22, and their classmates, it wasn’t merely an academic experience, but a deeply personal one.

“If you’ve read The Secret History by Donna Tartt or watched Dead Poets Society, I’d say it’s a bit like that,” says Stein. “Our little class would meet once every two weeks over the dinner hour. Jazz or folk would be playing in the background, the five of us nestled into plush chairs in the faculty lounge of the English building. [Hendrickson] has a rare gift for finding beauty and significance in everything. What becomes quickly apparent in his class is that there is no difference between writing well and living well.”

Hendrickson, Senior Lecturer in the Department of English, is a veteran author and journalist. Before coming to Penn, where he received a Provost’s teaching award in 2005, Hendrickson worked as a staff feature writer at The Washington Post from 1977 to 2001. He is the author of numerous books, the most recent of which, Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright, was published in 2019. He also authored the 2011 New York Times bestseller and National Book Critics Circle Award finalist Hemingway’s Boat: Everything He Loved in Life, and Lost, and in 2003, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Sons of Mississippi: A Story of Race and Its Legacy.

“Experience in writing long-form nonfiction gives the student-writer, who might one day try to make a vocation of this work, a sense of how hard it is to do something long and sustained,” says Hendrickson. “It makes them morally and ethically accountable to their subjects—that is, they are not just swinging by for one or two interviews, but they are building up a relationship built on trust: their trust of the subject, the subject’s trust of them. Trust is always the implicit bargain, whether it is ever stated as such or not. For the student to come to terms with this in a long-form project pays dividends they don’t even realize at the time.”

Students engaged closely with Hendrickson on topics until they landed on one that really resonated.

“The professor and I were on the phone over winter break trying to brainstorm some ideas for a long-form project before the start of the semester,” says Jinich. “Initially I was thinking of just following one person around for the entire semester, but he seemed to be really excited by the idea of a tone poem, a sort of noir perspective of Penn after midnight. He sent me a link to ‘Round Midnight’ by Thelonious Monk and it set my mind loose.”

The course, offered through Penn’s Creative Writing Program, maintained a small class size to maximize time for collaboration. Stein and Jinich’s classmates included Margaret Arfaa, C’24; Makena Deveraux, C’23; and Zachary Mullins, C’24.

Arfaa, whose grandfather was once highly connected at Annenberg, used storytelling to create a portrait of the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts.

Deveraux visited Penn Museum to study the complicated legacy of the photographic genius of Edward Curtis, the premier photographer and ethnologist of indigenous Americans in the early part of the 20th century. She examined archival prints and held in-depth interviews with the curator. Curtis’ photographs had a big impact on Deveraux’s mother, which made the project even more meaningful.

If you’ve read The Secret History by Donna Tartt or watched Dead Poets Society, I’d say it’s a bit like that. Our little class would meet once every two weeks over the dinner hour. Jazz or folk would be playing in the background, the five of us nestled into plush chairs in the faculty lounge of the English building.

Mullins took a deep dive into the life and teaching career of Richard Polman, Maury Povich Writer in Residence in the Center for Creative Writing at Penn, whose class Mullins had earlier taken, and who is responsible for Mullins’s pivot toward a possible career in journalism.

Jinich’s ultimate piece, Penn After Midnight, saw him exploring nocturnal happenings around campus. “Would I follow the quiet moments of students walking home from Smoke’s? The Allegro delivery driver? Rodin security guard? How can I represent the living and breathing campus that never sleeps?”

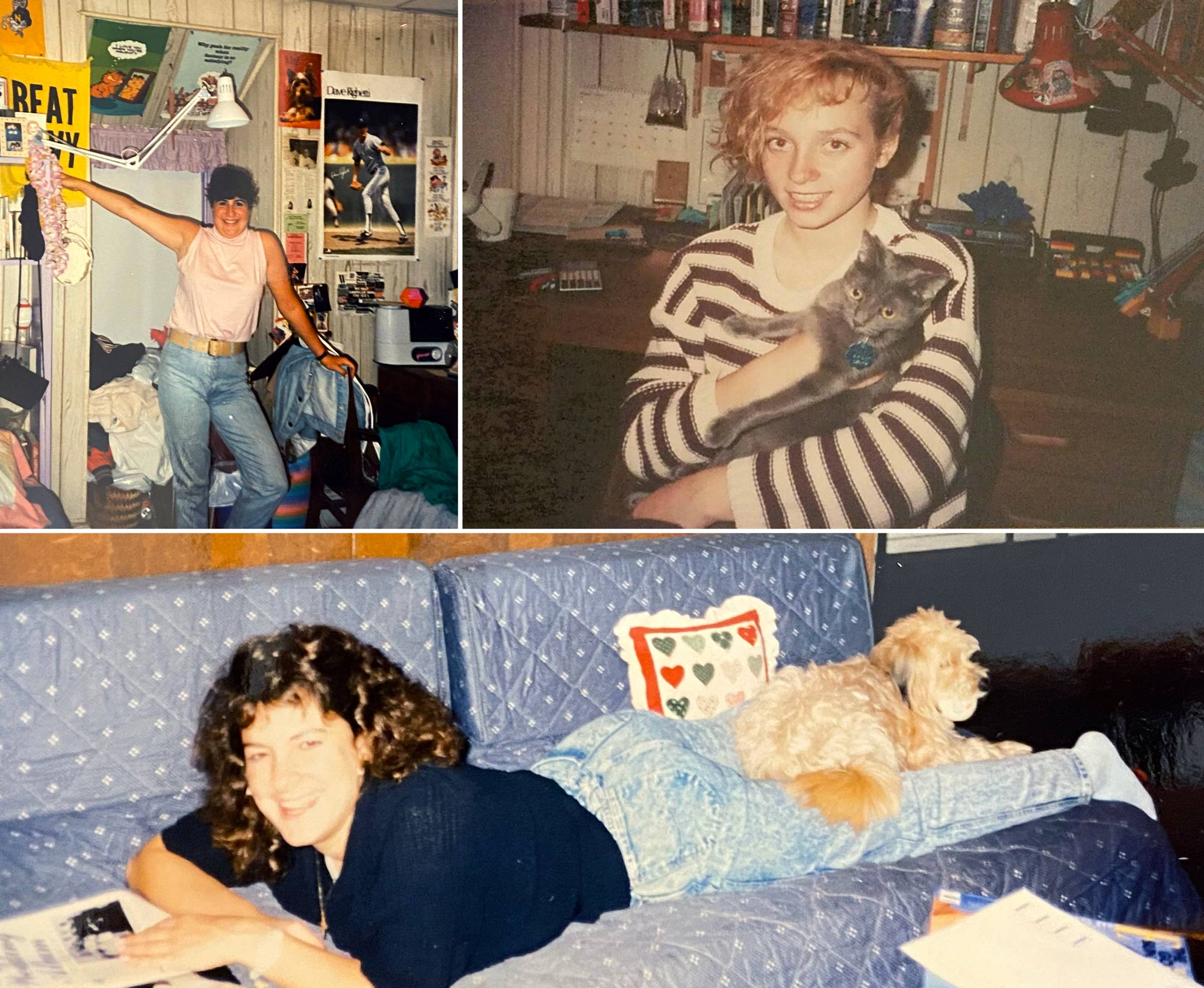

Stein’s piece, The Immortal Life of the Green Monster, delved into the storied history of her housing at Penn, which she and her roommates have affectionately dubbed the “Green Monster.”

“I’ve always loved learning about history,” says Stein, “so hearing first-hand about what it was like to be 20 years old and a student at Penn in 1970, or imagining what it might have been like to raise a family under the Green Monster’s roof during the Great Depression was such an amazing and all-consuming experience.”

In the following pages, Stein and Jinich share some of the most powerful passages from their pieces, giving us a glimpse into their work process and literary journey.

The Immortal Life of the Green Monster

By Lily Stein, C’22

What we made when we had to nothing to make // 2020–2022

We moved into the Monster in August 2020, height of the pandemic. Eight girls, planning to live there until graduation. In a simple world, the house was already a monument in the history of our lives—the last stop on our way out of college. But we carried in our many suitcases, second-hand furniture, and cardboard boxes with an appreciation greater than the run-down house probably warranted. It wouldn’t be just a monument to us, it would be a city.

We each had chosen a room when we moved in, which we meticulously and unintentionally personalized to become a physical manifestation of ourselves. When there was no longer space in the world for us, we had to make our mark somehow. Glitter and pink makeup smudged across Sandra’s desk next to her sewing machine, where she expertly tended to hemming her dresses shorter and shorter. Ivy’s minimalist room with the white bay windows. A framed black-and-white portrait of a young couple kissing on a train hanging on the wall to the right of her desk: spontaneity within limits. Sam lying in bed surrounded by her collected and carefully-sourced antiquities. Maeve upstairs with a canvas photograph of planet Earth larger than her modest, sparsely decorated room. Most of my junior year was spent wandering from bedroom to bedroom, each its own ecosystem.

What they tell me in broken memories // 1986–1988

Robyn, Ronni, Deborah, Amy, and I all occupy a small square of my computer screen. The four women are graduates of Penn’s class of ’88. Some of their lives have remained intertwined despite the geographic distance—Robyn and Amy are Nashville natives and have been friends since they were three—but Deborah and Amy have lived in the same city for twenty years and have only just realized this on the video call. They pledge to get a drink soon in Manhattan.

The women talk fast, talk over each other, laugh loudly, and go on long tangents that take us far away from the house. I listen, and later, I don’t attempt to transcribe the call as I did for the other residents I interviewed. Four years of shared history and thirty-four years of separate histories are being crammed into the call. There aren’t neat quotes that show me who these women were when they lived in my house as much as there are actions. Like the way everyone yells at Amy for not remembering certain stories or the way Robyn has kept every shred of paper accumulated since she was a freshmen living in the Quad.

What they took with them // 2009–2012

Charlie Oshinsky is the keeper of The Scroll. I have been told this by several of his housemates. He takes his job seriously—safeguarding The Scroll and carrying it with him through medical school, through various moves, through travels. The second I ask about his keeper status, he is walking to grab it. It has been ten or eleven years since a Green Monster “pledge” wrote out the Monster commandments on a piece of paper and dubbed it The Scroll, but Charlie still knows where that slip of paper is at all times.

He pulls out a tattered green folder. In chicken-scratch handwriting, he has written “Scroll” at the top of the folder, followed by “Birth certificate,” then “Social” underlined. He calls it his “folder of important documents” and it also happens to contain his medical license and the title to his car. But these don’t earn a spot on the title page. The Scroll comes first.

What we will remember together // Then & Now

We stand outside on the Monster’s deck and people-watch hordes of kids darting around to various pre-games, many clutching bottles of cheap champagne. David provides a running analysis on how the fashion trends have changed (“guys don’t wear tank tops anymore”) and how out-of-place he feels on campus (“I don’t remember the last time I went to a party”). His final Spring Fling in 2012, the Green Monsters had hosted their annual pre-game brunch and kept a running tally of how many times Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Call Me Maybe” played. Life was all neon and Fling parties were on campus. Style has since lost a lot of its color and the parties have moved to clubs downtown. David can’t wrap his head around this.

Before he leaves the deck—he has to get back to his girlfriend and the life of a 32-year-old adult—he tells me and Sam that he can see that we love each other and that it makes him happy to see. I smile and it reminds me of something he had said to me in an interview about the Monsters a few weeks ago: “I love them and I tell them I love them everytime I see them and everytime I say goodbye to them.” He still sees many of them every weekend. Their kids call him Uncle Fried.

The goodbye is coming soon for us, too soon. But I know we’ll be back standing on this deck one day, me and Sam. The music will be unrecognizable, the styles will have changed, and we will have changed with them. But we’ll be back all the same.

***

Click here to read Lily Stein’s The Immortal Life of the Green Monster in full.

Penn After Midnight

By Alan Jinich, C’22

Harrison Lobby, 1AM

Five security guards declined to speak with me before I approached Amber at the wrap-around desk in Harrison, a high-rise dorm built in 1970. She had arrived two hours earlier for her midnight shift and stood out with her sparkly headband warmer. A plastic barrier put up for COVID shields us from each other.

“I like the barrier,” she says. “I don’t really feel threatened by students here. But in the bar, people can become drunk and aggressive.” She used to bartend early morning shifts before becoming a security guard. It was an underground job at the height of COVID restrictions. “I couldn’t be a bottle service girl or server because there are no boundaries. Having that bar between me and the guest gives me more confidence…

“There are times where I look good and I feel good. I’m in the middle of the dance floor and well aware that everyone is looking at me. Throwing your hands in the air, losing yourself in a moment, the music. I love it. [She laughs]. Maybe it’s just liquid courage.” But behind this barrier she’s invisible. From midnight to 8am she pays bills, watches movies, writes goals, manifestations, to-dos, lists of people she would invite to her future wedding and people she would break money to if she ever won the lottery.

West & Down

There’s a line on 39th. It’s not crooked or straight, but sways with the pulse of music and breaks as bodies cut in. Fingers scramble through purses and wallets in search of driver’s licenses, foreign passports, spare cash. When Nasir raises his voice, the line stands on its tiptoes and turns to the front like a pack of meerkats. Nasir says, “straighten up”, and they straighten up. He folds fake IDs like cardboard and the line moves on. The 23-year-old bouncer of the West & Down nightclub is vigilant and assertive. No one gets in unless they comply.

“As I’ve grown older, I started to realize that not everybody has those opportunities to be able to process what they’ve gone through and then release it. So I come to a club with a whole bunch of college kids who are fresh outta their parents’ cribs, have had zero time to rectify all the trauma that they’ve been through, and they’re trying to figure out how to be an adult, pay for college. And now they gotta learn some shit. So when they come outside they just wanna let go of all that. I get it.”

Mask & Wig, 305

The door reads “Lewis: Hampstead, QC.” He opens the door with a smile and I introduce myself as a past resident. At first glance, his face reminds me of my younger brother’s.

The room is exactly as I remembered, except now it’s filled with Canadian sports memorabilia, posters, and hats. There’s even a TV.

Lewis sits up on his raised twin bed. I sit in his swivel chair and look up at him like my friends used to do for me. As in a dream, I feel that he’s taken my place.

“So do you like the room?” I ask.

“I’m fortunate to be here. You look outside and you’re nearly on Locust! And I’m a big history guy. I love tradition. As you can see by the room, I’m a diehard Montreal Canadiens fan. So it’s very cool to be part of a long standing tradition here. I get to sit here and look into that old world.”

Harrison Lobby, 2AM

I return to Harrison a few weeks later. The fireplace is turned off tonight. I ask Amber if she’s ever left Philly.

“I went to St. Thomas once. It had the most amazing weather. Waking up in that type of environment I thought how could you ever be sad? But it’s not home. Like I can’t get a cheesesteak around the corner. I can’t just pull up on my cousin’s.”

Her smile widens.

“As a young Black girl, there is like a certain culture. Meek Mill has a song called ‘Oodles O’ Noodles Babies’. It’s the pack of ramen noodles you get for like 25 cents at the store. And it’s just a staple for growing up in Philly. Like, if you were a young Black kid you grew up on that stuff. There’s a certain culture with being raised here. Like you’re gonna pass somebody that might not talk like you, look like you, dress like you. But somehow, someway, something links y’all because y’all from here.

“Do you think Penn feels like Philly?” I ask.

“I mean, Phil-a-del-ph-ia, the City of Brotherly Love, the Independence Hall, the book—the textbook Philly, sure. But the one I’m used to, the culture, no. Definitely not.”

***