When Penn students studied classics 100, or even 50, years ago, they focused on learning the ancient languages Latin and Greek, often building on their high school Latin. The texts they read in those languages were seen as giving access to a unique historical high point, a time of unrivalled achievement when the political systems, philosophical ideas, and literary and artistic forms that shaped modern America were first invented.

Those of us who teach classics today are still eager to give students the direct experience of ancient texts that comes from learning Greek and Latin and to share our appreciation of the impressive achievements of the ancient Greeks and Romans. But that vision of a superior, originary time has given way to a more complicated picture.

We now acknowledge how much mythology, poetry, art, and architecture the Greeks inherited from the cultures of the Ancient Near East. We are less willing to put classical societies on a pedestal, facing up to their many troubling features: militarism, imperialism, slavery, and misogyny. We recognize the historical zigs and zags that make it hard to claim that modern cultures really descend directly from classical antiquity. When, for example, the American founding fathers turned to the ancient world for models, they were trying to reestablish a connection that had been broken for many centuries rather than smoothly continuing a tradition.

Not only are contemporary students less likely to learn Latin before they come to Penn, they are also less and less exclusively people of European descent who might see themselves as direct heirs of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Our students often want to learn about the classical past, whether in a single course or a major, by reading Greek and Roman texts in English translation, and we now see producing those translations as a central part of our job.

We aim to present the classical world not as a purer, better ideal, but as a distant mirror that reveals contrasts as well as continuities with contemporary experience. Today’s dilemmas come into sharper focus when we consider the markedly different ways in which the Greeks and Romans conceived of such fundamental matters as race, religion, and sexuality. And we are not talking about a single monolithic culture. With its long time span, broad geographical range, multiple diverse societies, and many historical developments, the classical world offers many varied case studies for thinking through our own questions about migration, cultural contact, treatment of refugees, reintegration of veterans, and the effects of inequality.

When I teach a course on Periclean Athens, a period often assumed to typify ancient Greece, I make sure students understand that the system of democracy that developed there was one peculiar and contested form of government, not necessarily shared by other Greek cities or approved by all Athenians. I ask them to consider how much Athenian democracy resembled the contemporary American version, getting them to identify similarities and differences before deciding which features of the Athenian model they would or wouldn’t want to adopt: direct decision-making by the whole citizen body? Appointment to offices by lot? No participation by women?

The realization that we are only hearing one side of the story is essential for deciding what we can learn from antiquity’s misogynistic rhetoric and unequal gender relations (and here the mirror is not always as distant as we might like).

I also try to counter a monolithic view of the classical world by highlighting the fact that most of our evidence comes from writings by elite men. The realization that we are only hearing one side of the story is essential for deciding what we can learn from antiquity’s misogynistic rhetoric and unequal gender relations (and here the mirror is not always as distant as we might like). But we can also work to find women’s voices even in male-authored texts. Ancient epics build on and reflect a tradition of women’s laments; Euripides’ tragic heroine Medea may be stereotypically devious, jealous, and destructive, but she also gets to say how hard it is to be wife in a patriarchal household.

The muted and marginalized voices of antiquity can also be brought out through the study of reception: the long history of post-classical retellings of classical works. In a course on the afterlife of Homer’s Odyssey, I showcase contemporary women writers like Katha Pollitt, Louise Glück, and Margaret Atwood who have read between the lines of the Odyssey, developing hints that its heroine Penelope may not welcome her role as patient, faithful wife.

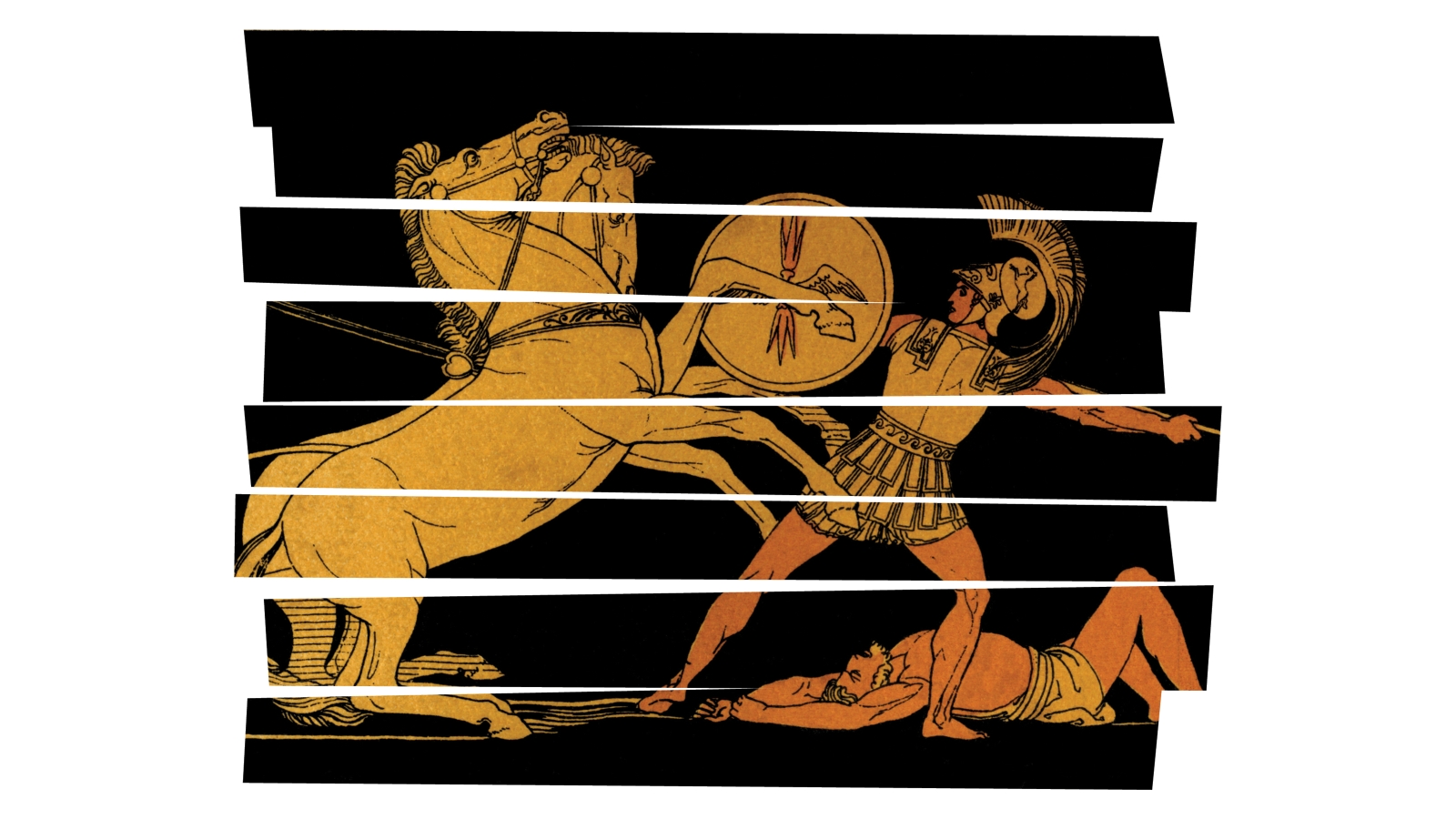

In a similar course on the Iliad, we read Alice Oswald’s Memorial, a selective rewriting of the Iliad in which the special deeds of the main heroes fall away and equal attention is given to every one of the warriors who die in the poem. Students in that course also visit the Philadelphia Museum of Art to grapple with Cy Twombly’s installation “Fifty Days at Iliam,” in which Homer’s epic is translated into ten canvases covered with vivid abstract shapes and scrawled letters.

Teaching how classical works have been reinterpreted over the centuries is a way of presenting them not as a set of treasures whose value is already self-evident, but as a rich cultural repository about which our students can decide for themselves how and why it should be valued.

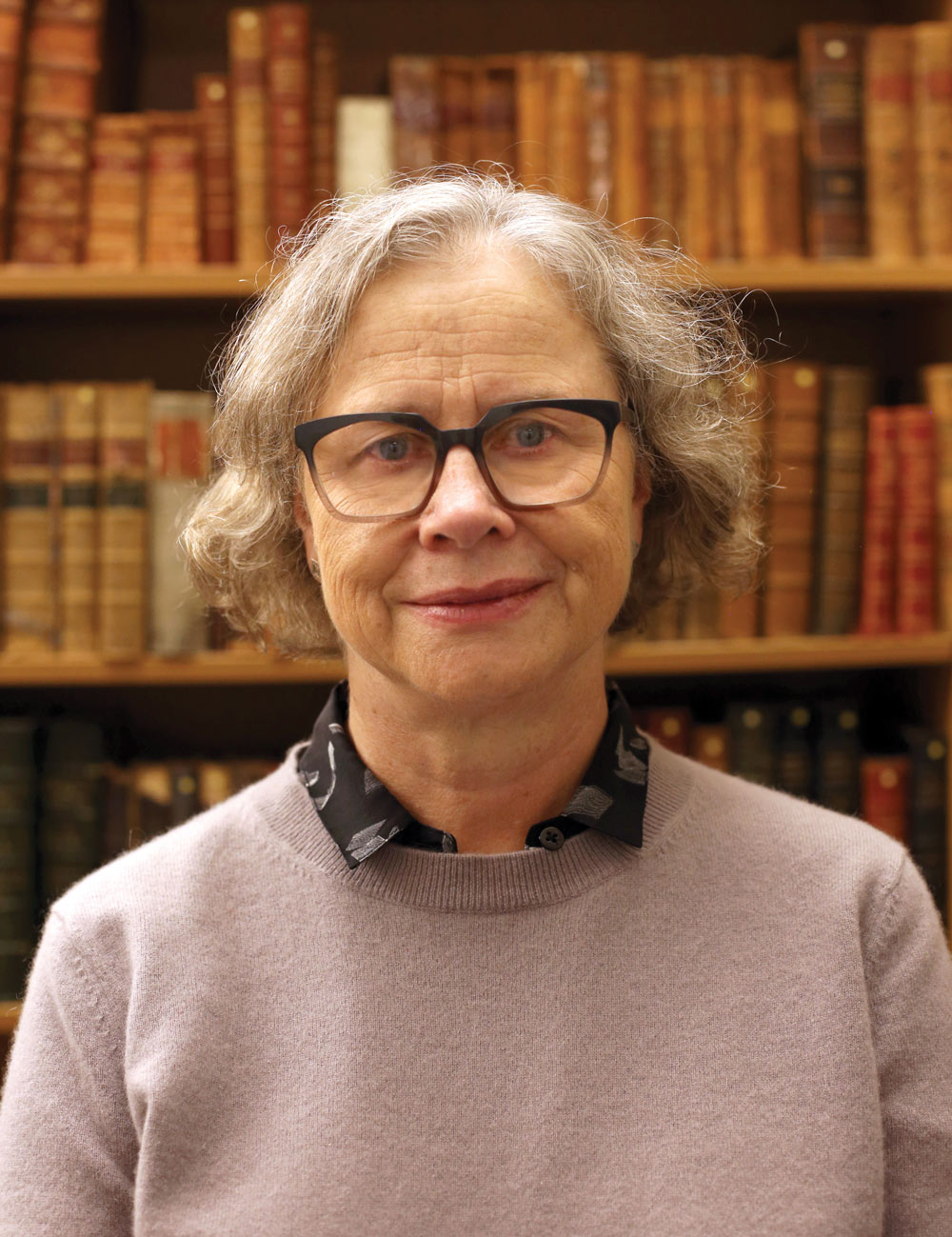

Sheila Murnaghan is the Alfred Reginald Allen Memorial Professor of Greek and President of the Society for Classical Studies. She is a 2019 recipient of the Lindback Award for Distinguished Teaching, the highest teaching award at the University.